Britain will be the only major economy to plunge into recession this year, performing worse even than sanction-hit Russia, as the cost-of-living crisis knocks UK households hard, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has warned.

The IMF predicts that the UK economy will contract by 0.6 per cent in 2023 against the 0.3 per cent growth it pencilled in last October in yet another major downgrade by the fund.

In its latest World Economic Outlook update, the IMF upped its growth outlook for the global economy, but cautioned that Britain looks set to suffer more than most from soaring inflation and higher interest rates.

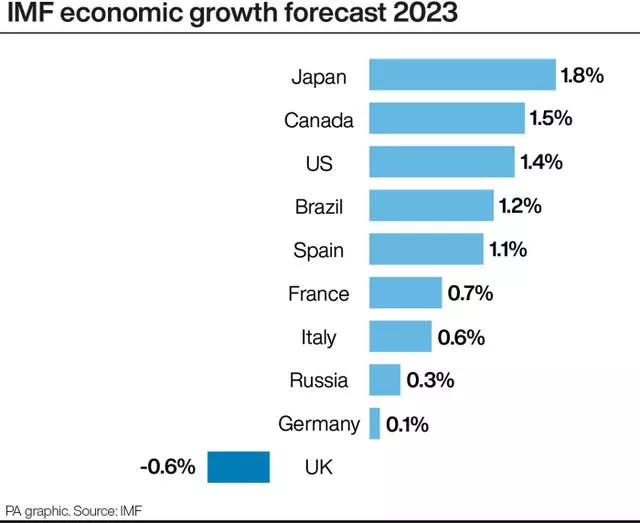

The grim outlook for the year ahead puts the UK far behind its counterparts in the G7 group of advanced nations and the only country, across advanced and major emerging economies, expected by the IMF to suffer a year of declining GDP.

Even Russia, which is under pressure from a raft of sanctions, is predicted by the group to eke out growth of 0.3 per cent.

Labour’s Rachel Reeves said the IMF forecast showed the UK was “at the bottom of the league table for growth” for both this year and the next.

The shadow chancellor, who was granted an urgent question in the Commons on the workings of the United Nations’ financial agency, told broadcasters that ministers needed to be “doing so much more to fulfil the potential of the UK economy”.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt stressed many forecasts were overly-pessimistic about the UK economy last year.

“Short-term challenges should not obscure our long-term prospects, the UK outperformed many forecasts last year, and if we stick to our plan to halve inflation, the UK is still predicted to grow faster than Germany and Japan over the coming years,” he said.

Among the other G7 nations, the IMF’s 2023 GDP predictions show growth of 1.4 per cent in the United States, 0.1 per cent in Germany, 0.7 per cent in France, 0.6 per cent in Italy, 1.8 per cent in Japan and 1.5 per cent in Canada.

It comes against a backdrop of public sector strikes over pay and predictions that the UK is heading for a recession, with inflation still standing at more than 10 per cent.

The IMF said Britain’s predicted GDP fall reflects “tighter fiscal and monetary policies and financial conditions and still-high energy retail prices weighing on household budgets”.

It follows efforts by Mr Hunt last week to talk up the UK economy and its growth prospects in his first major speech in the post, declaring that “declinism about Britain was wrong in the past and it is wrong today”.

The IMF offered a chink of light in the otherwise gloomy economic update, predicting that the global slowdown will be shallower than first feared.

It upgraded its global growth forecast, to 2.9 per cent in 2023 from the 2.7 per cent predicted in October as it said the reopening of China after strict Covid restrictions has “paved the way for a faster-than-expected recovery”.

The IMF also said it believes global inflation has passed its peak and will fall from 8.8 per cent last year to 6.6 per cent in 2023 and 4.3 per cent in 2024 as interest rate hikes by central banks begin to cool demand and slow price rises.

But it warned that, in the UK and Europe, surging prices and the impact of action taken to rein in inflation, will continue to weigh on the economy.

It said: “Consumer confidence and business sentiment have worsened.

“With inflation at about 10 per cent or above in several euro area countries and the United Kingdom, household budgets remain stretched.

“The accelerated pace of rate increases by the Bank of England and the European Central Bank is tightening financial conditions and cooling demand in the housing sector and beyond.”

But the IMF nudged up its outlook for UK growth in 2024 to 0.9 per cent, up from the 0.6 per cent expansion previously forecast.

Chief economist for the IMF, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, explained there were three key factors driving the UK’s economic outlook.

He said: “First, there is exposure to natural gas… we’ve had a very sharp increase in energy prices in the UK.

“There is a larger share of energy that is coming from natural gas, with a higher pass-through to final consumers.

“The UK’s employment levels have also not recovered to pre-pandemic levels.

“This is a situation where you have a very, very tight labour market but you have an economy that has not re-absorbed into employment as many people as it had before.

“That means there is less output, less production.

“The third is that there is a very sharp monetary tightening because inflation has been very elevated, that’s a side effect of this high pass-through of energy prices.”