It is virtually certain that 2023 will be the hottest year on record after four months of global temperature records being “obliterated”, climate scientists have said.

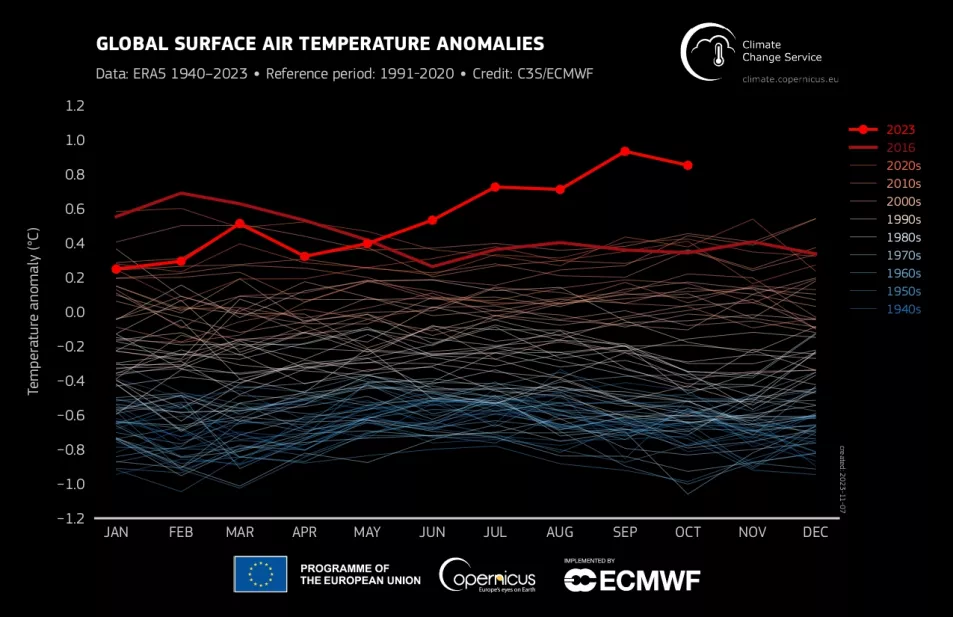

October was the hottest ever recorded, following the hottest September, August and July, the latter of which may have seen temperatures higher than at any point in the last 120,000 years.

The month was 1.7 degrees Celsius warmer than the pre-industrial average between 1850 and 1900 – the baseline against which scientists measure how much humans have warmed the Earth by emitting greenhouse gases.

So far this year, the average temperature is 1.43 degrees higher than this pre-industrial average, making it the hottest year on record.

With El Niño likely to continue into April 2024, according to the World Meteorological Organisation, it means the global average temperature will almost definitely remain at a record high over the next couple of months.

It added that this year is unlikely to go beyond 1.5 degrees, but even if it did the Paris Agreement goals would not be lost as that measure is taken over an average of multiple years.

October #Temperature highlights from the #CopernicusClimate Change Service (#C3S). Last month was the:

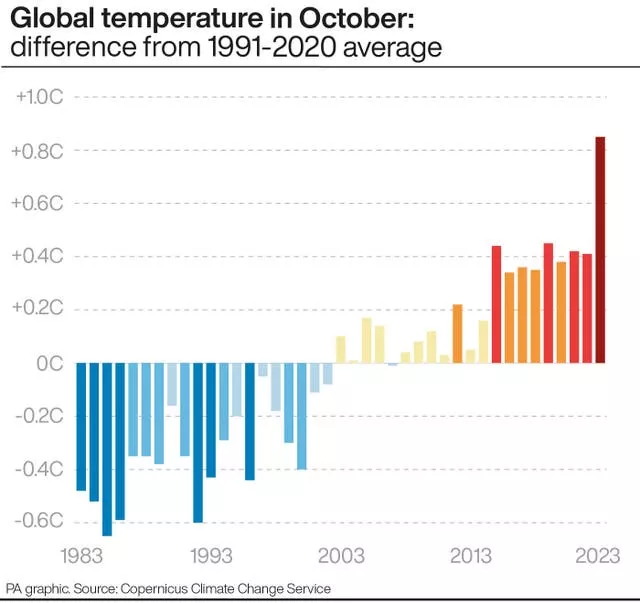

🌡 warmest October on record globally at 0.85°C above average;

🌡 4th warmest October for Europe at 1.30°C above average.

For more 👉https://t.co/DlWIUTIYed pic.twitter.com/oBHymzDwARAdvertisement— Copernicus ECMWF (@CopernicusECMWF) November 8, 2023

October’s average surface air temperature was 15.30 degrees, the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) said, which is 0.85 degrees above the 1991-2020 average and 0.4 degrees above the previous warmest October in 2019.

Last month was also the sixth consecutive month of Antarctica experiencing its lowest ever amount of sea ice for this time of year – 11 per cent below what it should be.

Samantha Burgess, deputy director of C3S: “October 2023 has seen exceptional temperature anomalies, following on from four months of global temperature records being obliterated.

“We can say with near certainty that 2023 will be the warmest year on record, and is currently 1.43 degrees above the pre-industrial average.

“The sense of urgency for ambitious climate action going into Cop28 has never been higher.”

El Niño is expected to last until at least April 2024. It is expected to fuel temperature increases and exacerbate extreme weather and climate-events, like heatwaves, floods and droughts.

New WMO Updatehttps://t.co/l5VJXkRf5K#StateofClimate #EarlyWarningsForAll pic.twitter.com/PnagiJVUQU— World Meteorological Organization (@WMO) November 8, 2023

Continued heat into the autumn has led to wildfires burning more than 2,500 hectares in the Spanish province of Valencia, forcing 850 people to leave their homes.

Fire seasons are becoming longer around the world as high temperatures persist after summer, adding extra strain on the emergency services tasked with saving life and property.

Dr Friederike Otto, senior lecturer in climate science at the Grantham Institute, Imperial College London, said: “I think the most important thing to highlight here is that this is not just another record or another big number that is statistically interesting.

“The fact that we’re seeing this record hot year means record human suffering.

“Within this year, extreme heatwaves and droughts made much worse by these extreme temperatures have caused thousands of deaths, people losing their livelihoods, being displaced etc.

“These are the records that matter. That is why the Paris Agreement is a human rights treaty, and not keeping to the goals in it is violating human rights on a vast scale.”

Ireland had a very mild October this year, especially during the first third of the month with record October maximum temperatures in places, according to Met Éireann.

Nine weather stations in Ireland have already experienced rainfall above the long-term average for autumn with one month remaining, after Storms Babet and Ciarán cause flooding in the south and east of the island.

Scientists have said Ireland will become warmer and wetter because of climate change as the atmosphere holds 7 per cent more water with every degree of warming.

Grahame Madge, of the UK Met Office, said warming trends mirror that of global warming over the last 10 years although there can be strong variations in local weather.

He said: “What happens at a global scale doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s exactly mirrored by what happens on a local scale.

“If we were to get a cold period or a relatively mild period, that’s independent of what happens globally, to some extent.

“Where there is a stronger connection is the fact that weather patterns generally, even cold extremes like the Beast from the East, were probably a little bit warmer than they would have been without the signal of climate change, because the fingerprint of climate change is now on most weather records and it just nudges them up by a bit.”