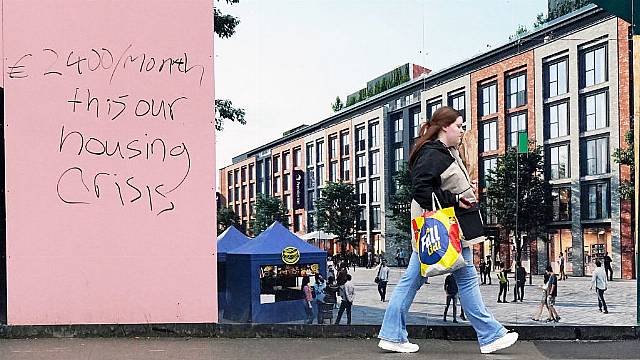

Ireland's housing shortage is an era-defining crisis that will be the main battleground for politicians in the general election.

Housing consistently ranks as a top concern for the Irish public. In the spring 2024 Eurobarometer poll, 64 per cent of people in Ireland cited housing as one of the two most important issues facing the country.

The housing crisis is also complex and difficult to navigate – whether you’re a tenant, a prospective house buyer, a landlord or a homeowner considering selling.

The breakingnews.ie housing tracker provides a regularly updated overview of the key metrics in Ireland’s housing sector, such as property prices, rents and new home construction, to help make sense of the issue.

House prices are now more than 12 per cent above their boom-time peak, according to the Central Statistics Office (CSO). Property prices nationally have increased by 150.7 per cent from their trough in early 2013 after the financial crisis.

Property prices vary significantly across the country – from a median of €142,000 in Castlerea, Co Roscommon, to €720,000 in Dublin 6. Yet, regardless of location, the cost of buying a home has reached unprecedented heights.

Several factors are contributing to the high prices. The main driver is a shortage of houses available for purchase. Demand has also remained strong, fuelled by population growth and a robust economy. This is despite the sharp rise in mortgage interest rates since 2022.

Government initiatives like the Help to Buy and First Home schemes have also boosted demand amongst first-time buyers.

Green Party leader Roderic O’Gorman has said the Help to Buy scheme should be reviewed, after a party TD said the policy may have a “link” to rising house prices.

The scheme is designed to help first-time buyers purchase a newly built house or apartment as well as one-off self-build homes.

It offers a tax rebate of up to €30,000. However, opposition parties have claimed that the scheme has an inflationary effect on house prices.

A financial stability note from the Central Bank found that average users of the scheme tend to be higher-income borrowers who buy larger, more expensive homes.

However, not everybody wants or is in a position to buy a home. A large chunk of Ireland's population now relies on the private rental sector, which has seen significant price increases in recent years.

The Residential Tenancies Board (RTB) publishes a quarterly rent index which documents the prices paid by existing tenants and those taking up new tenancies in the private rental sector.

Dublin consistently has the highest rents, while parts of Donegal and Leitrim offer the lowest rental prices in the country.

Rural counties are now experiencing the largest growth in rents. According to the RTB’s figures for the first quarter of 2024, prices for new tenancies in counties Leitrim and Longford surged by 22.6 per cent and 22.5 per cent respectively on an annual basis.

Among cities, Dublin had the highest average rent for new tenancies at €2,084, followed by Galway at €1,720. Limerick city recorded the greatest annual increase in rent levels, rising by 18.3 per cent to €1,522.

The RTB data also reveals that sitting tenants continue to pay lower rents than new tenants.

The national standardised average rent paid by new tenants is €1,612 per month, which is €221 or 15.9 per cent higher than existing tenants who pay an average of €1,391.

This difference is partly explained by rent pressure zones (RPZs), which are areas in which annual rent increases for sitting tenants are capped in line with the rate of general inflation or 2 per cent a year, whichever is lower.

Shannon in Co Clare is the latest area to be designated an RPZ.

One of the most severe consequences of the housing crisis is the rising number of people experiencing homelessness.

A new record was set in September when 14,760 people were recorded as living in emergency accommodation, including 4,561 children.

There is consensus across the political spectrum that Ireland needs more new homes.

Under the Housing for All plan, the Government pledged to build an average of 33,000 new homes each year from 2021 to 2030.

Last year saw the highest level of residential construction since the Celtic Tiger era with just under 33,000 units completed.

However, new home completions have slowed during 2024, putting the Government’s target of 33,450 completions this year at risk.

There were 21,664 new dwelling completions between January and September this year, the CSO found, a fall of 3.1 per cent on the same period last year.

Officials have admitted that housing targets up until this year have been “significantly below” the actual requirement of 50,000 homes per year.

The Government has now published revised housing targets for the years ahead, but they do not include separate targets for social, affordable, rental and private ownership homes.

Data from the National Planning Framework, the Housing Commission and the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) fed into the new targets.

The ESRI previously said housing demand is projected to be approximately 44,000 per year until 2030, but that projections of housing demand are “very sensitive” to assumptions regarding migration.

For 2024, the Government’s target is 9,300 social homes, 6,400 affordable and cost-rental homes and 17,750 private ownership or rental homes.

While the Government reached the overall target of new builds in 2022 and 2023, it has so far failed to reach the target number for social housing.

Last year the new-build social homes target was missed by 1,000, with only 8,100 homes completed.

The Department of Housing was also not able to use its full capital spending budget in both years, leaving €471 million unspent in 2022 and €140 million in 2023.

The failures were blamed on supply issues and a shortage of builders.

The department typically funds local authorities and approved housing bodies to build social homes through the Social Housing Investment Programme; the Capital Advance Leasing Facility and the Capital Assistance Scheme.