Parties vying to lead the next Government are luring voters with ambitious spending plans, banking on a continued boom in foreign multinational corporate tax revenues that could be threatened by the incoming US administration.

With a strong economy, a population set to rise by up to 8 per cent by 2030 and infrastructure provision 25 per cent lower than many other high-income European countries, whichever party wins the November 29th general election will need to spend more just to keep up.

However, the scale of the commitments and potential risks have become a theme of the campaign. An Irish Times headline on Sunday suggested "someone should take Simon Harris's phone away before he bankrupts the country", noting the Taoiseach's nightly unveiling of "all sorts of goodies" on Instagram.

"The US election has appreciably changed the risk, and we seem to be going ahead as if nothing has changed, but I think something very significant has changed," said Professor John McHale, head of economics at the University of Galway.

The risk centres around the unique exposure of Ireland's low-tax business model to the United States. Ireland's recent big budget surpluses have been driven by a near seven-fold increase in corporate tax receipts over the last decade, mainly paid by US firms.

Precarious position

If enacted, US president-elect Donald Trump's pledge to slash corporate tax rates to Irish levels, incentivise industries to bring production back to the US and impose trade tariffs could jeopardise the continued growth in corporate tax receipts forecast by the Department of Finance.

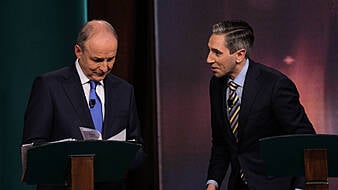

Mr Harris' Fine Gael and outgoing coalition partner Fianna Fáil - the favourites to lead the next government - have promised to hike spending by 5.5 per cent to 7 per cent a year to 2030, cut taxes and invest the remaining surplus in the country's sovereign wealth fund.

Sinn Féin favours a higher level of spending growth and putting less money aside.

The plans suggest recent "fiscal slippage" will continue after the election, Goodbody Chief Economist Dermot O'Leary said, calling on parties instead to stick with a fiscal rule introduced in 2021 to cap spending increases at 5 per cent a year.

The outgoing government broke its own rule in three of the four budgets since its introduction.

Not everyone agrees that the international risks should spell more caution, given Ireland's improved financial balance sheet and debt dynamics.

"We have a good hand to deal at the moment and I think that's reflected in some of the optimism you're seeing in the policies," said Kevin Timoney, chief economist at Davy Stockbrokers.

"We have this big infrastructure gap and we have money to try close it and that can help support the medium term picture. We don't want to be laggards in some of these areas that are strategically important for the economy."