Former Northern Ireland first minister Arlene Foster has denied “sectarianising” Stormont’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic by deploying a controversial veto mechanism to prevent the extension of restrictions.

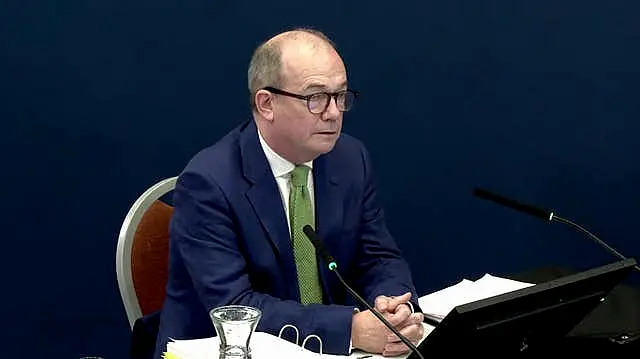

Giving evidence to the UK Covid-19 Inquiry in Belfast, the former DUP leader conceded the row in November 2020 marked a “low point” in the Executive’s handling of the pandemic and she acknowledged the use of the cross-community vote damaged public confidence.

The controversy unfolded during a series of back-to-back Executive meetings across four days, which saw all the other parties in the devolved coalition administration push for a two-week circuit breaker extension to restrictions, as recommended by health officials.

However, the DUP, which was concerned about the economic effect of continued closures of close-contact services and coffee shops, deployed the veto mechanism to stop the majority opinion from holding sway.

The other parties heavily criticised the use of the cross-community vote, which was designed during the peace process to protect minority interests, in the context of a health emergency.

On Wednesday, Ms Foster defended using the mechanism, insisting Sinn Féin had also triggered it in the past on issues that were not “constitutional” in nature.

During her evidence to the inquiry, the former first minister also:

- Described how she felt personally upset by the attendance of then deputy first minister Michelle O’Neill at the large-scale funeral of veteran republican Bobby Storey despite lockdown restrictions.

- Said no other DUP ministers agreed with a claim made by former Stormont minister and party colleague Edwin Poots that Covid-19 was more prevalent in nationalist areas.

- Expressed “great regret” that Stormont did not anticipate the speed with which the Covid-19 pandemic spread.

- Acknowledged a political row over the closure of schools in the North at the outset of the pandemic reflected very badly on the Executive.

- Branded “offensive” the suggestion that the North had “sleepwalked” into the pandemic.

In regard to the cross-community veto episode, Ms Foster accused Ms O’Neill, who was chairing the relevant Executive meetings, of forcing the issue of extending restrictions to a vote among ministers, rather than trying to seek consensus through negotiations.

Lead counsel to the inquiry, Clair Dobbin KC, asked the baroness if she accepted that the DUP’s use of the mechanism “sectarianised effectively the most pressing and critical of issues, going to the health and the life of people in Northern Ireland”.

“I don’t accept that it sectarianises it because it’s a mechanism that’s been there since 1998 (Good Friday Agreement) for key decisions,” the former DUP leader replied.

“I think it was a key decision for a lot of people in Northern Ireland that we were going to take their livelihoods away again.”

The former first minister admitted the cross-community veto was a “blunt tool” and told inquiry chairwoman Heather Hallett that it may well be replaced by a system that uses weighted majorities in the future.

“It was pushed to a vote and we ended up in a position where relationships almost broke down, frankly,” she said.

“And then we had to take some time out to try to come back together again trying to find a way forward. And it was very difficult to watch from the outside, I’m sure. It was torturous inside. And I hope that we never get to a place where we have a four-day meeting of the Executive again.”

Ms Foster added: “I really regret that we couldn’t find consensus and we were forced into that position. It certainly wasn’t a good look for the Executive and I regret that it had to be used.”

At one point during the hearing, the former first minister was shown text messages chief medical officer Dr Michael McBride had sent after the November 2020 meetings – in one he suggested the politicians should “hang their heads in shame” and in another, he described the events as “politics at its worst”.

Ms Foster said she was “saddened” by Dr McBride’s assessment.

The former DUP leader was also asked about the furore surrounding the funeral of Mr Storey.

On Tuesday, while appearing at the inquiry, Ms O’Neill apologised for having attended the funeral in June 2020.

A day later, Lady Foster told the inquiry the incident caused difficulty in their working relationship, and left her feeling unable to stand on a joint platform with the deputy First Minister for press conferences.

“It was a huge disappointment and indeed caused massive damage to the Executive, to the credibility of the Executive to public messaging and was very hurtful to so many people around Northern Ireland who had stuck by what were very stringent rules around funerals and wakes,” she said.

“All of that had been prohibited and yet here was one of the people making the rules actually doing just that. It was a huge disappointment, personally, I felt very upset about it all and I didn’t feel there was any credibility in going back to a press conference at that time.”

At the outset of her evidence, the baroness expressed “great regret” that Stormont did not anticipate the speed with which the Covid-19 pandemic spread.

She said by mid-March 2020, ministers had been advised the peak of the first wave was still 14 weeks away.

In the event, the powersharing administration found itself triggering the first lockdown before the end of that month.

Lady Foster said as first minister and joint head of government she accepted her responsibility for the outcomes in Northern Ireland during the first wave, including for the outbreaks within care home settings.

However, she defended her leadership of the coalition in Belfast during the pandemic.

While conceding others may make a different assessment of her performance, she insisted she “tried to do the best for the people of Northern Ireland”.

The former first minister referred to advice given by chief medical officer Dr McBride in mid-March 2020 that the peak of the first wave was 14 weeks away.

“So, wrongly, and I say absolutely wrongly, we felt that we had time and we didn’t have time,” she said.

“And that’s a source of great regret.”

The former Assembly member was asked by Ms Dobbin whether she felt she gave the leadership the people of Northern Ireland deserved during the pandemic.

“It was probably the most difficult period of my political career,” she replied.

“I think it has been set out that I’ve had a quite long political career. But I can say without any hesitation that dealing with the Covid pandemic was the most challenging, the most difficult time, and I’ve had some difficult times.

“But we certainly tried, as all of the Executive, I think tried to put their best foot forward to deal with the issues that were presented to them.

“We had had three years without a government [during the 2017-2020 powersharing impasse]. We had come back on January 11th [2020]. We had a lot of things to do, because there hadn’t been a government for three years, and we were then confronted with this global pandemic coming towards us.

“So it was hugely challenging. And I think all I can say in regards to my own leadership, is that I certainly tried to do the best for the people of Northern Ireland recognising that I was first minister at the time.”

Ms Dobbin repeated the question on whether she gave the leadership that the people deserved.

“Well, I think that’s a subjective question,” responded Ms Foster.

“Other people will have particular views on whether they got the leadership they deserve. I can only answer it from my own perspective, and I certainly gave as much as I could.”

She added: “From my perspective, I gave the leadership that I felt was needed at that time.”

Ms Dobbin put it to the former politician that a feature of her written statement to the inquiry was her seeking to blame “other people or other departments” for what happened during the pandemic, particularly the Department of Health.

Ms Foster rejected that characterisation of her statement.

However, she pointed out that the Department of Health was the lead department in the Covid-19 response.

“That’s why Michelle [O’Neill] and I looked to the health department for information in relation to the coronavirus,” she added.

“So that’s not a passing of the buck, it’s just the reality that we didn’t have the information in relation to what was happening.”