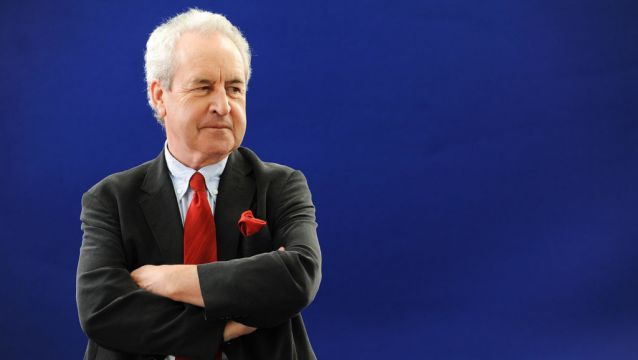

Irish author John Banville – former Booker Prize-winner and literary master, whose novels have been lauded both at home and abroad – is reflecting on the death of his wife in 2021.

“I couldn’t work at all for the first six months,” says Banville, 77, who recalls suffering with “brain fog” in his grief.

“Nothing helps you through, you just get through it. You just live in a very strange state. It’s like nothing you expect. It’s like having an endless hangover. You can’t really do anything, it just goes on,” adds the author, whose late wife was the American-born textile artist, Janet Dunham.

“But I’ve been very fortunate in my life, especially in the women I’ve known and my two daughters, and my two sons. I’m more fortunate than I deserve to be.”

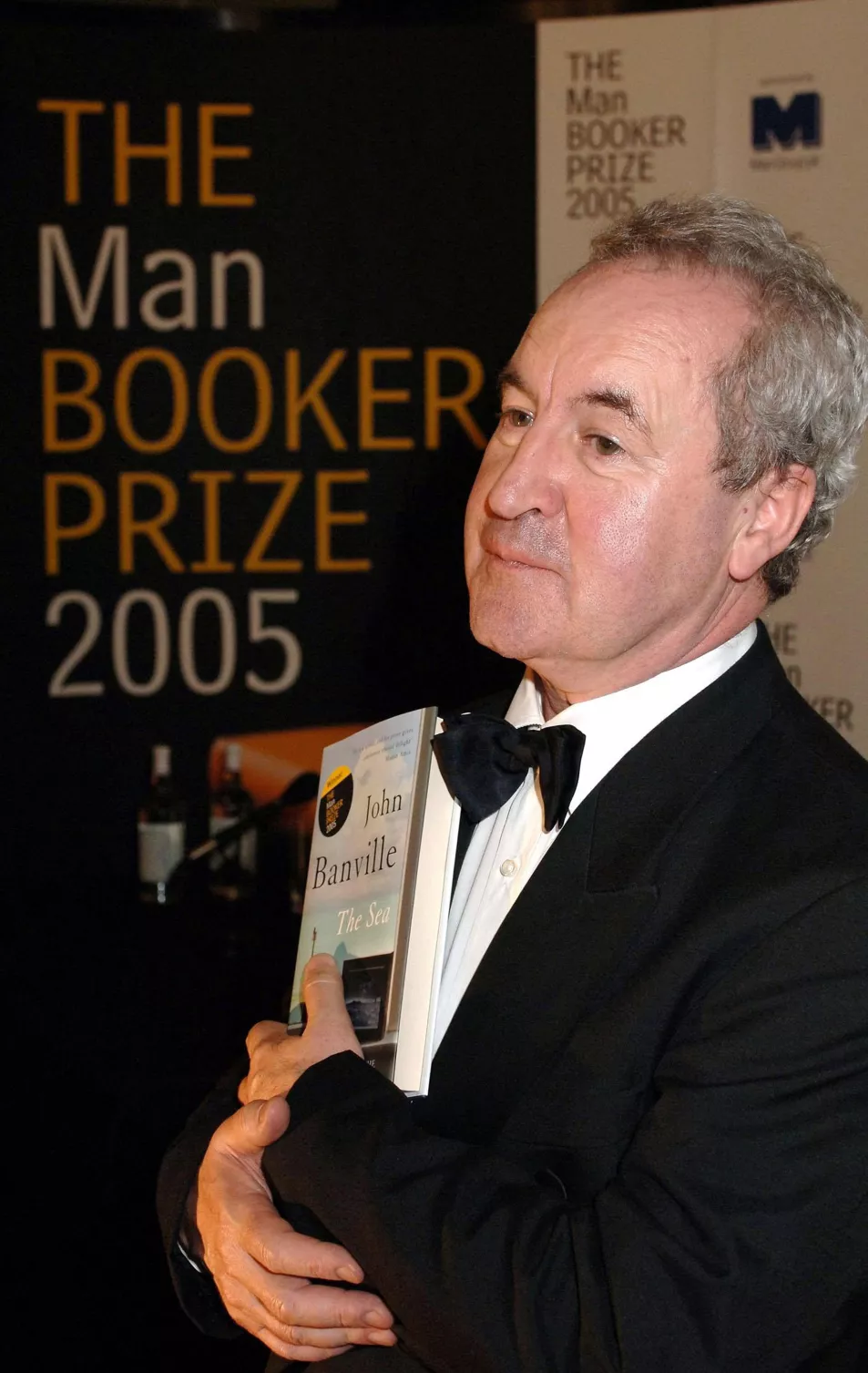

The Wexford-born writer, famed for his poetic and sensory fiction, won the Man Booker Prize in 2005 for The Sea.

More recently, he has made waves with his crime novels set in the 1950s featuring his charismatic but troubled pathologist Dr Quirke – which spawned a TV mini-series starring Gabriel Byrne in 2014. They have been written largely under the pen name of Benjamin Black and more recently under his real name.

The subject of grief creeps into his latest, The Lock-Up, a murder mystery set in the 1950s in which the body of a young woman is discovered in a garage in Dublin.

It finds Quirke – who is still grieving over the death of his own wife while in the first throes of a potential new romance – once again teaming up with Det Insp Strafford, a Protestant officer in the Garda, a predominantly Catholic police force, who has appeared in some of Banville’s previous books.

Did his own experience of bereavement filter into the pages? “It probably did. I certainly have first-hand experience of grief now, which I didn’t when I wrote before,” Banville reasons.

He and his late wife, with whom he had two sons, remained on good terms after the breakdown of their marriage but never divorced, and he still talks about them being married for more than 50 years although, by his own admission, the situation was “complicated”.

“I had another partner with whom I had two daughters while my wife was alive, so there’s sin for you, and guilt, but my wife and I stayed friends throughout our lives.”

Unlike some contemporary crime novels, which arguably lack literary finesse, The Lock-Up is beautifully written by this master of language. At times, the plot seems somewhat secondary to the setting and atmosphere of both domestic and work environments in 1950s Ireland, as the chalk-and-cheese pathologist and detective rub along – frequently rubbing each other up the wrong way.

The nostalgic details of the period are ever-present – Senior Service cigarettes, sherry served in tulip-shaped glasses, agitation for pro-abortion and contraception in a country where at the time, pregnancy was still the worst misfortune that could befall an unmarried female.

The son of a garage clerk, Banville was born in 1945 – so the 1950s is the era in which he grew up, and one he finds fascinating. After working as a clerk at Aer Lingus, he became a sub-editor at The Irish Press and later literary editor at The Irish Times.

Celebrating John Banville's birthday, I'm indulging in a few fantasies of my own. I #amwriting #scifi

Happy Birthday John Banville (aka Benjamin Black), award-winning #Irish #writer and #screenwriter - https://t.co/FjmWpgwq5Y#author #quote #JohnBanville #TuesdayFeeling pic.twitter.com/4AKd7kTVWR— PJ Braley (@PJBraley) December 8, 2020

His love of crime fiction began when he read Georges Simenon in 2003 – which was when Banville decided to write the genre himself. He wrote many of his earlier crime novels under the pseudonym of Benjamin Black.

“I assumed I would be writing just one crime book and decided I should write this under a pen name, simply to avoid the danger of my readers thinking this was some kind of elaborate post-modernist literary joke. But in retrospect, I shouldn’t have written under a pseudonym.”

He’d also read Raymond Chandler as a teenager – and wrote a new Philip Marlowe (the trench-coated detective) novel decades after Chandler wrote the first. The recent movie adaptation of his 2014 novel, The Black-Eyed Blonde, simply called Marlowe, stars Liam Neeson in the titular role.

“With all my crime books, I never know what I’m doing or where I’m going. For this one, I went to this writers’ place in the depths of the country to finish the book where there’s nothing – no pubs, no restaurants, no distractions.

“I had to leave on Saturday and on the Friday night, I thought, I don’t like the way this book is going. Oh, hang on – I know another ending to it. So I sat down on Saturday morning, and I wrote the last chapter and I didn’t even read it. I just sent the manuscript off to my publishers.

“The point I’m making is that not only should crime fiction be well written but it has to be spontaneous, with that sense of sudden discovery. I don’t plan my books at all. I never know what’s going to happen.”

His non-crime novels take him much longer to write. His last one, The Singularities, took him six years. In contrast, he writes each murder mystery in about four months.

“Real professional crime writers hate me when I say that, but Georges Simenon used to write his books in 10 days.”

Yet, he hates reading back his books.

“It’s like a dog returning to his vomit. I only see the flaws, I only see the failures, the clumsiness, the bits that I got wrong. I can’t stand reading my own work. It makes me physically ill.”

He doesn’t read any contemporary crime fiction. “I’m not interested,” he says simply. Non-fiction art books, poetry, history and philosophy are on his reading list. “I write more fiction now than I read.”

As a successful writer, he is no fan of ‘sensitivity edits’ and describes the recent editing of Roald Dahl books to remove language deemed offensive as “disgraceful”.

Banville says: “It’s childish. Children love Roald Dahl because he’s so awful. Children are completely ruthless. We have to grow up in order to learn to live with others in a halfway civilised world but children are not like that.

“Robert Louis Stevenson used to call his books like Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde ‘crawlers’, books that make your flesh crawl. Children love that and it’s good for them. But also, you must not change the text. Better to suppress the text altogether than to change it. That’s an outrage. And Roald Dahl is dead, he can’t defend himself.”

What would he do if publishers attempted to change his work?

“I’d tell them ‘No!’ It could be that my work be changed after I’m dead by some 23-year-old failed creative writing class person with a grudge. That’s a horrible prospect.

“But this is a fad that will pass with other fads, but a lot of damage will be done along the way.”

Today, he lives in a village outside Dublin with one of his sons and hesitates when asked if he’s lonely. “I’ve always been solitary, but I haven’t been lonely because people have been very good to me.”

He doesn’t know what he would do if he didn’t write. A new crime book and some screenplays are among his current projects.

“It’s a childish occupation writing fiction. You just sit there making up stories, like we did when we were little,” he quips. “What would I do if I retired? My wife used to say, ‘You’d give up writing, go into politics and destroy the world’.

“I live to work and I can’t imagine what I’d do if I didn’t.”

The Lock-Up by John Banville is published by Faber. Available now.