The biggest barriers to blood donations in ethnic minority groups in Ireland include lack of information and a history of living in a malaria-endemic region, a report has found.

Factors that motivated people among non-Caucasian groups to give blood included religious reasons and a desire to help others in their own communities.

The findings were published in a study by RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences which identified barriers and motivators to blood donation for people from ethnic minority groups.

The findings of the survey will assist in addressing the recent blood shortages in Ireland and will enhance the diversity of the blood supply.

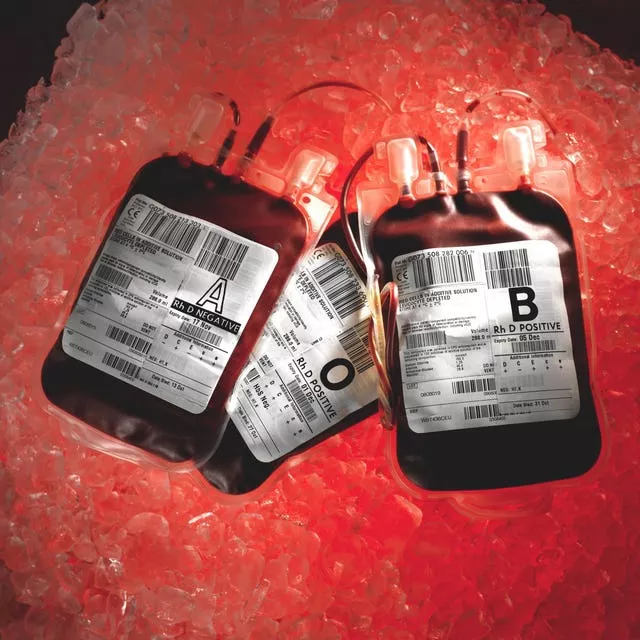

Current shortages have potentially serious consequences for patients who require blood transfusions, particularly patients with sickle cell disease, an inherited blood disorder that affects red blood cells.

Sickle cell disease is particularly common among people with an African or Caribbean family background.

The findings are published this week in the journal Blood Transfusion, in advance of World Sickle Cell Day on Sunday, and is the first of its kind to explore ethnic differences in blood donations across different ethnic groups in Ireland.

Overall, the most common barrier to blood donation, identified by 58% of respondents, was lack of information on blood donation, with 30 per cent reporting they were deemed to be ineligible at the blood donation centre and 35 per cent citing “other” barriers.

The most common self-reported reasons for ineligibility included history of living in a malaria-endemic region, anaemia and/or iron deficiency, height or weight restrictions, temporary deferrals, including new piercing, tattoo and exclusion due to a medical condition.

Other self-reported barriers included fear of blood and fear of fainting.

Uncommon hurdles included religious barriers (2 per cent), belief that there is enough blood in the healthcare system (5 per cent), distrust of the healthcare system (5.5 per cent) and men who have sex with men (MSM) in 8.5 per cent of male respondents.

Only 2.4 per cent reported a personal history of a sexually transmitted infection such as HIV, Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C and no respondent reported these infections in their partners.

The most commonly identified motivators included being asked by a family member or friend (95 per cent), knowing someone who required blood transfusion (93 per cent), greater availability of information about blood donation (88 per cent), being a “rare” blood type (87 per cent) and donating to “help someone in my own community” (83.8 per cent).

Promotion of donation on social media and on TV/radio were motivators in 67 per cent and 66 per cent, respectively.

Religious motivators, including donation if suggested by a religious group and proximity of donation centres to places of worship, were reported in 43 per cent and 35 per cent respectively.

Overall, 84 per cent of respondents were aware of conditions like SCD and Thalassemia, with 83.9 per cent indicating they would be more likely to donate if they knew more about these conditions and 96 per cent if there was a shortage of blood for these conditions.

Lead researcher Dr Helen Fogarty, of the school of pharmacy and biomolecular sciences at RCSI, said the timing of the research is crucial.

“Ireland has experienced major blood shortages recently with the result that for the first time in over 30 years, blood has been imported from the UK,” Dr Fogarty said.

“There is an urgent need now to increase blood donations, including from people from minority ethnic groups.

“The results of this study help us to understand why these groups are under-represented and will help us to include people from different ethnic backgrounds in blood donation in future, making a huge difference for all patients who need blood transfusions.”