The recent heatwave was perhaps the first time many wished they had access to air conditioning in Ireland, as the country’s first “tropical night” in 20 years made sleep difficult.

While heatwaves “have always happened, and always will happen,” Met Éireann meteorologist Dr Padraig Flattery says, there is no doubt that their intensity and frequency is altering due to climate change.

Dr Flattery, from the national forecaster’s climate services and research division, says 19 of the last 20 years in Ireland have been above average temperature, and most of our hottest years have occurred recently.

“There's no question at all that Ireland is warming,” he says. “Over the last 100 years since 1900, we've increased by about one degree, so 0.9 to one degree is what our observations show.”

The trend looks set to continue, with recently updated climate projections indicating Ireland can expect a “greatly” reduced need for heating and a small increase in air conditioning requirements by the middle of the century – a time period just 20 to 40 years from now.

Models on future temperatures, heatwaves, frost days, rain and snowfall are all being mapped out at the Irish Centre for High-End Computing (ICHEC), with the research funded by and carried out in collaboration with Met Éireann, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Marine Institute.

Dr Paul Nolan, climate science programme manager at the ICHEC, works on simulating the future climate by running long-term global and national climate simulations on supercomputers.

Here, the scientists take global models of the planet’s future climate and “downscale” them to Ireland, localising them to four-kilometre areas to create regional climate models as far ahead as 2100.

Just one simulation can take up to six months to run, Dr Nolan says. A large number are run to reduce uncertainty, so that when the majority of models agree on a projection – such as future dry summers – the scientists can have confidence in it.

So what does the future hold?

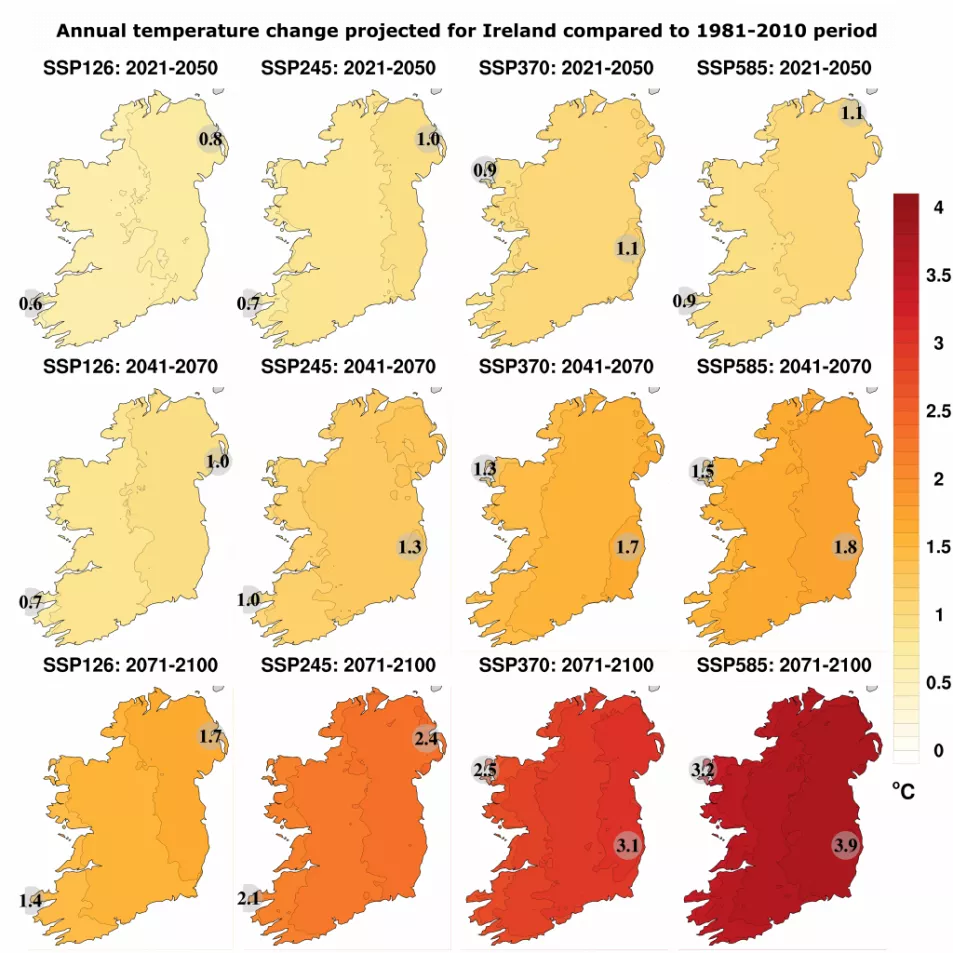

According to the latest update to mid-century projections for the years 2041 to 2060, temperatures will increase, heatwaves will be more frequent, frost and snowfall will decrease, there will be more dry periods, but also more heavy precipitation events.

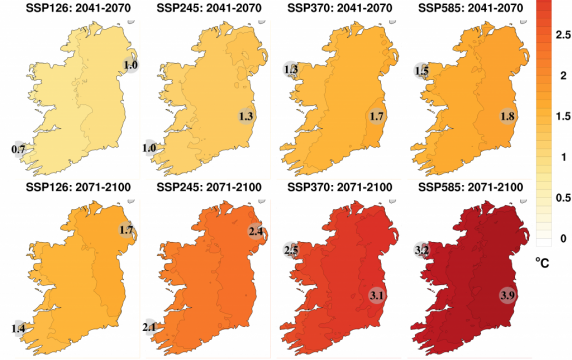

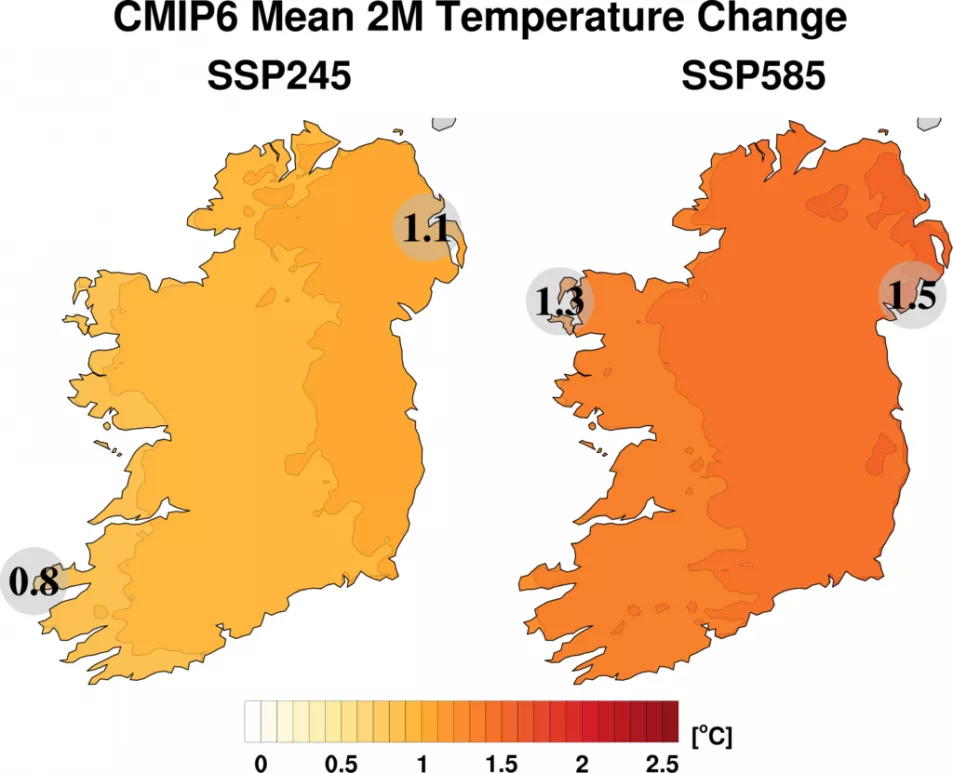

Average temperature increases between 0.8 and 1.5 degrees will be seen when comparing the future period with the past period of 1981 to 2000 – ranging between 0.8 to 1.3 degrees in the west and 1.1 to 1.5 degrees in the east.

Lower increases are based on a scenario where the world curbs its greenhouse gas emissions, while higher increases are the more likely result if little is done on a global scale.

“People say, ‘oh one or two degrees, that’s not much at all,’ but it is. One or two degrees, that’s the mean over the full year, but you’ll get much higher extremes,” Dr Nolan says.

Under all emission scenarios, warming will be “enhanced at the extremes”, meaning both hot summer days and cold winter nights will experience greater temperature increases than the averages projected.

Under a higher emission scenario for summer daytime temperatures, highest daytime temperatures will rise by two degrees in summer in the southeast by mid-century.

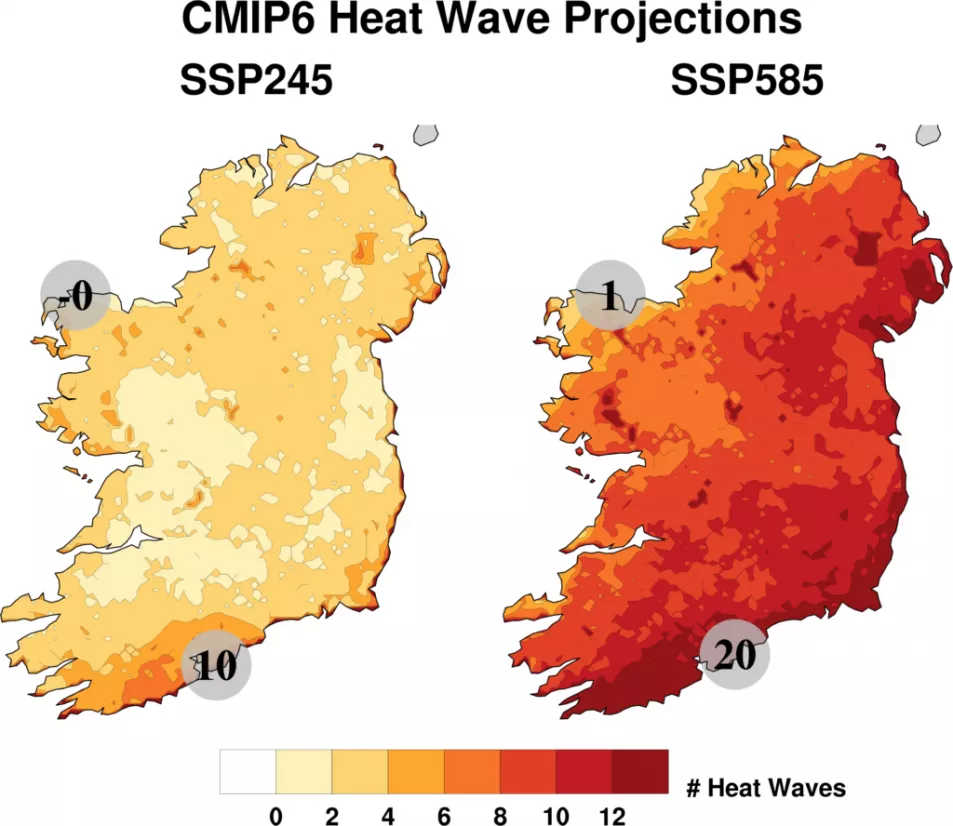

Summer heatwave events are expected to occur more frequently, with the largest increases in the south. 10 additional heatwave events are projected there over the 20-year period of 2041 to 2060 under a lower emission scenario, compared to the period of 1981 to 2000.

Under a higher emission scenario, the number of heatwaves over the 20-year period will increase by 20.

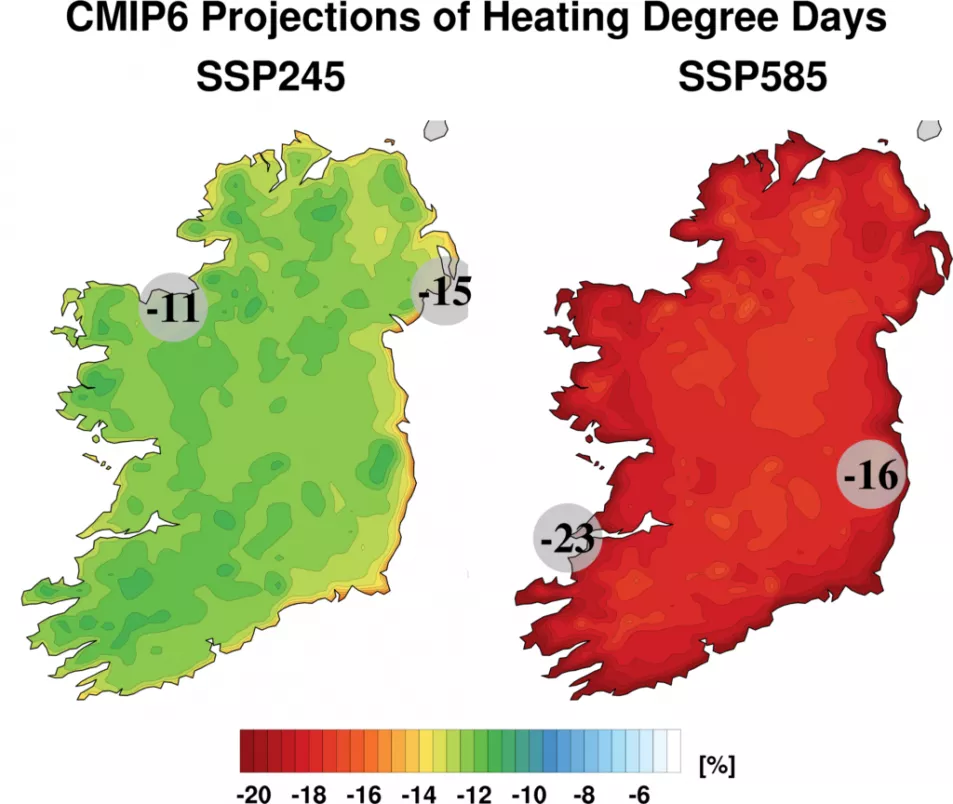

Projections also show a “greatly reduced” requirement for heating in Ireland, with the number of days requiring heating by mid-century decreasing by 11 per cent in the west and 15 per cent in the east under a lower emission scenario.

Under a higher emission scenario, days requiring heating will reduce by 23 per cent in the west, and 16 per cent in the east.

A “small increase” in air conditioning requirements will meanwhile be most pronounced in the east and midlands.

Precipitation is expected to become more variable, with “substantial projected increases” in both dry periods and heavy precipitation events. Annual specific humidity is also projected to increase substantially.

As for frost, the number of days when the minimum temperature is less than zero degrees is projected to decrease by 50 per cent.

Snowfall is also projected to decrease substantially by the middle of the century, with reductions of over 30 per cent according to the latest projections.

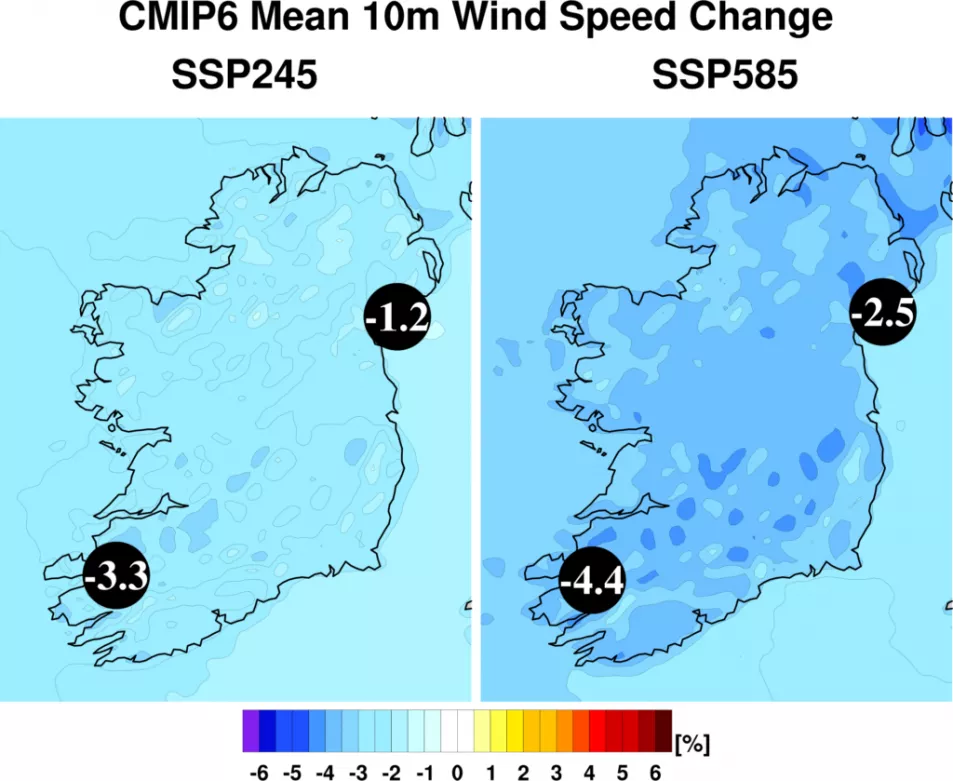

Both solar and wind energy sources are also projected to decrease in Ireland.

These preliminary results, from the downscaling of simulations from a group of international climate modelling institutes labelled CMIP6 (Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6), are so far in “broad agreement” with previous CMIP5 ones – indicating confidence in the projections.

What is clear is that the degree to which Ireland’s climate will change depends on how much greenhouse gas emissions are emitted in the coming years.

Dr Nolan says ranges within the climate projections are based on four greenhouse gas standard emission scenarios (SSPs), ranging from an optimistic low-emission scenario to a pessimistic high-emission one.

The most optimistic ‘SSP126’ scenario “assumes that the world shifts gradually towards a more sustainable path,” with global emissions peaking between 2010 and 2020, and declining substantially after that.

The pessimistic ‘SSP585’ scenario meanwhile assumes “rapid and unconstrained ‘fossil-fuelled’ growth in economic output and energy use with emissions continuing to rise throughout the 21st century,” Dr Nolan says.

'It all depends on the next 20 years'

Met Éireann’s Dr Flattery says “it all depends on how much we emit over the next 20 years.”

“So if we, let's say, reduce emissions quite significantly, then we will see less warming in future, but if we go on as we currently are, then we’ll see far more warming,” he says.

“If we meet our emissions targets, if we stick to this goal of limiting climate change or limiting global warming to one and a half degrees, then we won't see significant changes and that will be the biggest success,” he says.

“But it's less likely that that will happen as time goes on, and more likely that we will end up with a situation in the kind of mid-range, so we will do something but we may not do enough to limit the warming.

“And then, we really aren't 100 per cent sure, it's all models... there’s a phrase that all models are wrong, but some are useful. And these models are certainly useful in telling us what the impacts might be.”