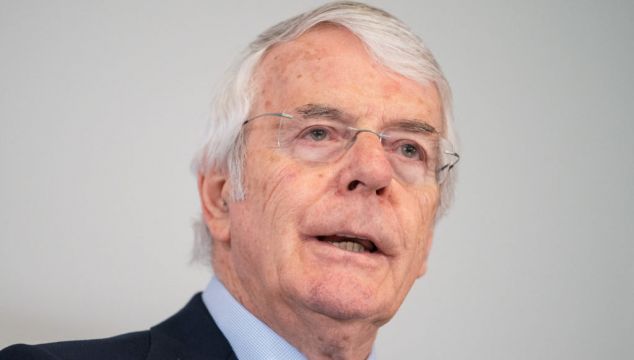

Former UK prime minister Sir John Major has said that no party or group should put peace in Northern Ireland in peril.

Mr Major also criticised the Northern Ireland Protocol as “one of the least well-done negotiations in modern history”.

Just months ahead of the 25th anniversary of the Belfast/Good Friday peace deal, the Stormont Assembly remains collapsed, with the DUP refusing to take part until issues around the protocol are resolved.

The DUP argues the protocol undermines Northern Ireland’s position within the UK and hampers trade with Great Britain.

Talks remain ongoing between the UK and the EU over the protocol, part of the post-Brexit deal which keeps Northern Ireland aligned with some EU trade rules, effectively placing a trade border in the Irish Sea.

Mr Major was speaking at a meeting of a committee in the Oireachtas on Thursday.

The Joint Committee on the Implementation of the Good Friday Agreement is examining the peace accord 25 years on.

Mr Major outlined his part in the lead-up to the deal during his premiership from 1990 to 1997.

He stressed that, to him, violence was as unacceptable in Northern Ireland as anywhere else in the UK, and he worked towards peace, adding that he visited the North more often than anywhere else as prime minister.

He recalled working with Taoiseachs including Albert Reynolds – who he described becoming a cherished friend – and John Bruton, and the start of a back channel communication between the UK government and the Provisional IRA.

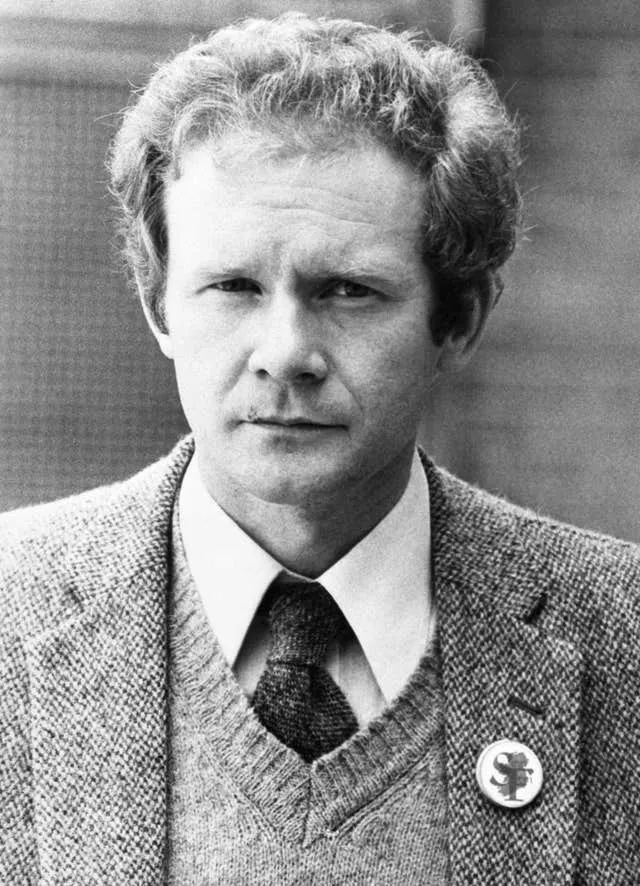

Mr Major repeated his assertion that he was assured the first message which helped set up the back channel came from former Sinn Féin vice president Martin McGuinness.

Mr McGuinness, who is now deceased, denied that during his life.

“If he didn’t send it, I think it is clear he was aware it was being sent and of the substance,” Mr Major added.

Mr Major expressed his revulsion at a number of terrorist atrocities, including the IRA bombing of Warrington in 1993, in which two boys – Tim Parry and Johnathan Ball – were killed, saying it almost brought the peace process to a halt.

He described the Downing Street Declaration in December 1993 as providing a start. Ceasefires followed in 1994 and all-party talks started in 1996.

The Belfast/Good Friday Agreement came in 1998 after Labour’s Tony Blair had become prime minister.

Mr Major told the Oireachtas committee the peace process was not down only to politicians, but to the Northern Ireland community, the churches, individual clerics and groups such as the peace women.

With political uncertainty remaining in Northern Ireland, Mr Major urged that the peace not be placed into peril.

“I hope that no one person, no group, no political party – and no ideology – will now risk imperilling the peace so carefully constructed by so many, for so long,” he said.

Asked about the protocol, Mr Major described a “very poor negotiation” and said it “must be put right … and the sooner the better”.

“I doubt there is a perfect solution, so often there isn’t,” he told the committee.

“It will mean a degree of flexibility on both sides of the negotiation, a degree of flexibility in London and a degree of flexibility in Brussels, there must be a way to improve the present circumstances even if it is not perfect.

“I think it is very important that it is treated as a matter of priority, to get that agreement, because it will enable the Executive to meet again, it’ll enable the other political problems unconnected with the peace process to be dealt with by elected politicians in the north, and it will go a long way to improving the relationship between London and Dublin.”

Mr Major also dismissed arguments over sovereignty in the protocol row as “semantic”.

“If there were to be movements under Article 16 to disapply parts of protocol, I don’t think an ideological concern about sovereignty would justify that, because the sovereignty point is, in terms of the extent to which it is applied in the Northern Irish question on trade, is semantic quite frankly,” he said.

“I don’t think anybody on the extreme fringes of politics should be in a position to wreck what has been brought together by the mainstream politics.

“I don’t think anybody, whatever their personal concerns might be, really have a moral right to break apart the Good Friday Agreement and put us at risk to returning, if only partially, back to the troubles that existed before the Good Friday Agreement was finally signed.”