While critics have welcomed the fact four Irish writers have made this year’s Booker Prize long list, there has also been criticism that Anne Enright, Dublin-based literary star and former winner of the much coveted literary gong, has not.

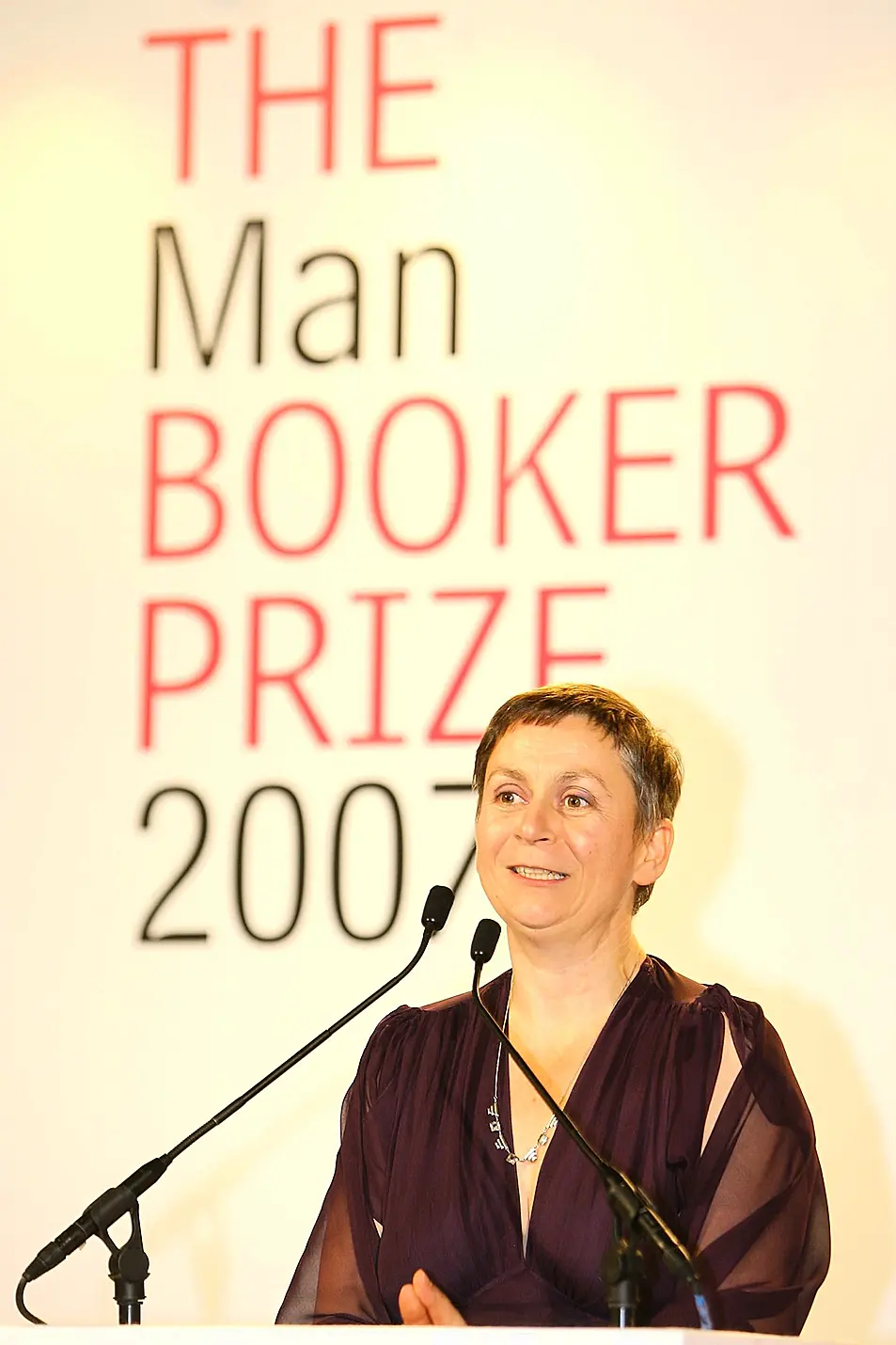

The 60-year-old writer and former RTÉ TV producer, whose latest novel, The Wren, The Wren, has received wide critical acclaim, reflects: “Well, I feel that I won the Booker Prize in 2007 (with her dark novel, The Gathering) and that may have been a factor.

“But it’s a new and adventurous list, a list that’s very interested in discovery. I benefited from a similar impulse back in 2007. I wasn’t all that well known. But I think it would be ungracious of me to complain.”

She says awards always beg questions about the cultural moment and cultural authority, who has the right to bestow an award on someone and why. But there is a place for them, she adds.

“The book business has been fighting for them for years and it has been encroached by the shift to online and places like Amazon. Despite that, books thrive, and the readership always seems to be growing, but it has been a nervous two decades for the book trade and prizes are great PR machines, apart from anything else.”

Her latest literary gem, which took three years to write, charts a familial story set around three generations of women and the effect a rustic Irish poet Phil McDaragh – husband, father and grandfather to the three respectively – has on their lives and their connections. His poems and translations are peppered throughout the novel as timelines of thoughts and emotions.

Most of the focus is placed on 22-year-old Nell, Phil’s granddaughter, and her mother, Carmel (his daughter), as the story unfolds through their different perspectives.

The narrative alternates between the suffering he put both Carmel and her mother Terry through, leaving his wife for a life in America when she was in the throes of cancer, and the thoughts of Nell, an energetic young character who never knew her grandfather but has tattoos on her body which reference his work and who takes comfort in his writing.

Nell has her own problems, including a dodgy Irish boyfriend Felim, who overwhelms her physically and emotionally and, like her late grandfather, is unreliable and untrustworthy.

Enright, a mother-of-two, often centres her novels around women. She was asked early on in her career why she wrote books which were so unhappy.

“It was the equivalent of walking down the street and being told to ‘cheer up, love’ by the building site workers,” she says. “The idea that women should write books that console us and offer solace and cheer everybody up… I just grew out of that anxiety.

“I thought it was an astonishing question to be asked, why your books are so sad? They just are. It’s one of the uses of fiction, to explore the darker side of humanity.”

When she became the first Laureate for Irish Fiction, a post she held from 2105-2018, she found what she calls a “hidden and unconscious bias” when examining statistics of which works of fiction were reviewed in major Irish newspapers, finding there was a tendency by at least one of them not to review work by women.

“It was a big surprise to everyone. No one noticed. And I just found it thoroughly satisfying and a little bit frightening to do, because then people did actually notice.”

It made a difference that she was calling out that unconscious bias from a position of authority, rather than a place of complaint, she observes.

“It’s interesting when you are being discriminated against, broadly speaking, that people don’t hear what you’re saying when you complain – that it’s just women banging on. But when you do it from a place of authority, being the Laureate for Irish Fiction, that actually did make a difference to how people heard what I had to say.”

Things have improved, she says, but unconscious bias needs to be monitored.

“If you take your eye off it, it returns insidiously. I thought that after the pandemic, things went slightly back to the good old male days, not in the newspapers but maybe in the festivals and other cultural spaces. If you take your eye off it in times of uncertainty, that bias does have its effect.”

After her tenure, she was delighted to return to writing books and enjoying a lower profile.

Does she mix with an enclave of famous Irish writers?

“Dublin has no VIP room,” she responds. “So any book event in Dublin is going to have any number of upcoming, established or working authors there, along with all kinds of family and friends. It’s a relatively small place. So you’re going to know people.

“I was at a book launch a couple of weeks ago and John Banville was there, but also unpublished writers from my class at UCD (she teaches creative writing at University College Dublin). So I don’t have a gang or a clan.”

Married to Martin Murphy, adviser to the Arts Council of Ireland (they met when she signed up for the drama society during freshers’ week at Trinity College Dublin and he was the director), she says she runs her work past her husband.

“He’s very useful. He finds things out. He can point out patterns and help me see what I’m doing. He’s not super involved but he is with the work.”

She’ll be going on a book tour in the UK, Canada and the US, but knows how to reboot, with cycling holidays and taking the dog for long walks.

“I went for a big long walk every day during the lockdown and that was great for my mental health. I’m pretty sane, but thanks for asking,” she say wryly. “And I have family here and we are all looking after our mother, who’s very elderly. Tending your connections is really important.”

The next book will happen when it happens, she says simply.

“In the old days, I wouldn’t go three weeks without writing fiction but I haven’t been writing fiction now, maybe because I’m interested in those bigger ideas. As I get older, the ideas are larger, undercurrents rising to the surface.”

As for awards, and for a writing career in general, it’s a competitive world, she agrees.

“You’re putting so much into making a distinctive work. You really want to make a mark separate to your peers. That’s very much the case with younger writers. But they also get a lot from hanging out with each other,” says Enright. “But I’m a bit too old to be hanging out with other writers.”

The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright is published by Jonathan Cape. Available now.