Researchers from Swansea University have analysed the remains of a cat, a bird and a snake, in “extraordinary detail, right down to their smallest bones and teeth”.

They say the findings, published in the journal Scientific Reports, provide insights into the animal mummification process as well shed light on the conditions in which the animals were kept and their possible causes of death, without causing damage to the specimens.

While previous investigations had identified which animals they were, not much was known about what was inside the mummies.

Study author Dr Carolyn Graves-Brown, from the Egypt Centre at Swansea University, said: “Our findings have uncovered new insights into animal mummification, religion and human-animal relationships in ancient Egypt.”

Ancient Egyptians created animal mummies for various reasons – some were household pets buried alongside their deceased owners, while others were intended as food offerings to humans in the afterlife.

But the most common animal mummies were created to serve as sacred offerings to the gods.

Scientists believe there may be up to 70 million mummified animals buried in underground catacombs across Egypt.

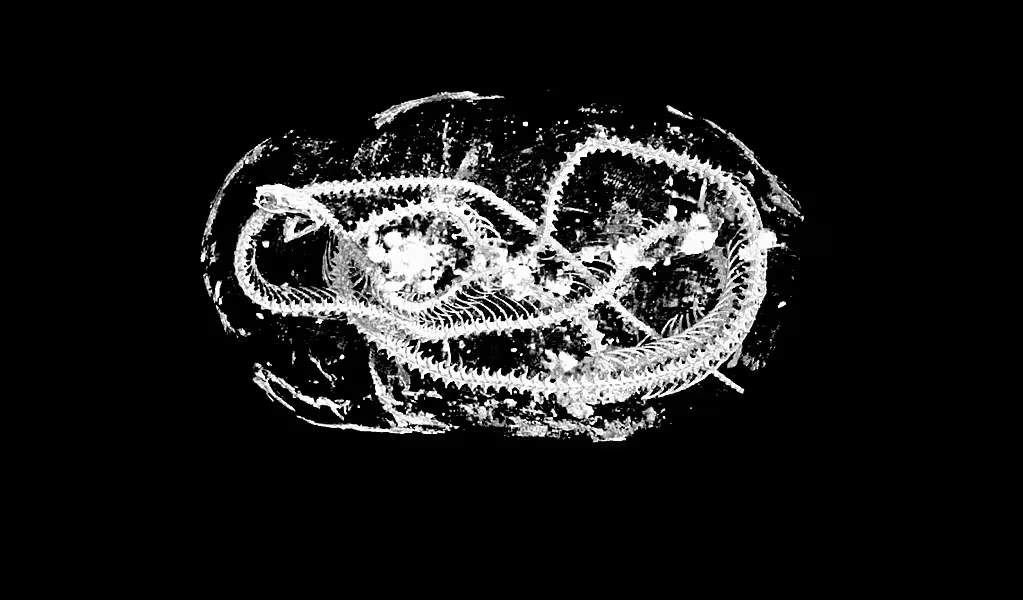

The researchers, led by Professor Richard Johnston of Swansea University, used an advanced form of imaging technique, known was X-ray micro CT scanning, to generate 3D images of the animals.

Based on an analysis of the teeth and skeleton, the researchers believe the mummified feline was a kitten less than five months old.

They also found gaps between the neck bones, which, according to the team, indicates the kitten may have had its neck broken at the time of death or during the mummification process to keep the head in an upright position.

The tightly-coiled mummified snake was identified as a juvenile Egyptian Cobra, which may have died from spine damage “consistent with tail capture and whipping methods”.

The researchers also found evidence of kidney damage in the snake, which suggests it may have been deprived of water during its life.

The high-resolution imaging also allowed the scientists to identify what they believe to be hardened resin in the mouth of the reptile, which they speculate may have been added during the Opening of the Mouth ceremony – an ancient Egyptian burial ritual.

Meanwhile, bone measurements and 3D scans of the bird suggests it most closely resembles the Eurasian kestrel.

Prof Johnston said: “Using micro CT we can effectively carry out a post-mortem on these animals, more than 2,000 years after they died in ancient Egypt.

“With a resolution up to 100 times higher than a medical CT scan, we were able to piece together new evidence of how they lived and died, revealing the conditions they were kept in, and possible causes of death.”

He added: “There are estimated around 70 million mummies that were produced at the time in ancient Egypt.

“And through this technology, we just investigated three very different types – a cat, a snake and a bird.”

Prof Johnston said his work could provide a template for future investigations, “potentially revealing lots of new insights into the animal lives at the time and also the people of the time – how they lived and worked, and the religious practices”.