Americans have begun casting ballots in the midterm elections after a campaign that exposed the country’s political divides and raised questions about its commitment to a democratic future.

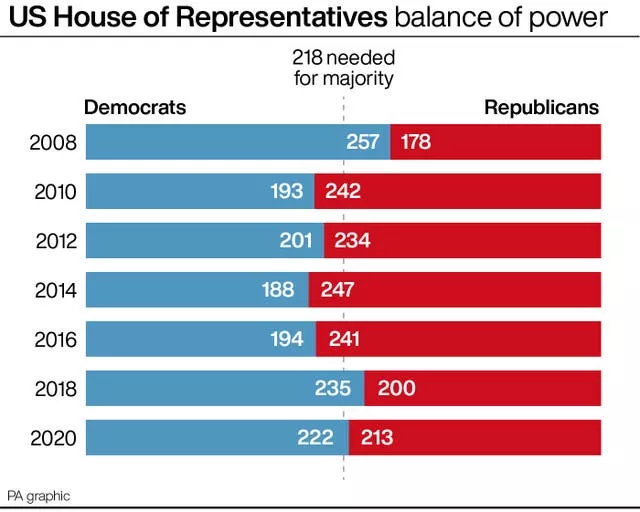

Democrats were braced for disappointing results, anxious that their grip on the US House may be slipping and their hold on the US Senate has loosened.

The party’s incumbent governors in places like Wisconsin, Michigan and Nevada are also staring down serious Republican challengers.

Returning to the White House on Monday night after his final campaign event, President Joe Biden said he thought Democrats would keep the Senate but acknowledged “the House is tougher”.

The Republican Party was optimistic about its prospects, betting that messaging focused on the economy, fuel prices and crime will resonate with voters at a time of soaring inflation and rising violence.

Ultimately, they are confident that outrage stemming from the Supreme Court’s decision to eliminate a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion has faded and that the midterms have become a more traditional assessment of the president’s performance.

“It will be a referendum on the incompetence of this administration,” said Minnesota Republican Tom Emmer, who is running efforts to retake the House.

The results could have a profound impact on the final two years of Mr Biden’s presidency.

Republican control of even one chamber of Congress would leave Mr Biden vulnerable to investigations into his family and administration while defending his policy accomplishments, including a sweeping infrastructure measure along with a major healthcare and social spending package.

An emboldened Republican Party could also make it harder to raise the debt ceiling and add restrictions to additional support for Ukraine in the war with Russia.

If Republicans have an especially strong election, winning Democratic congressional seats in places like New Hampshire or Washington state, pressure could build for Mr Biden to opt against re-election in 2024.

Former president Donald Trump, meanwhile, may try to capitalise on Republican gains by formally launching another bid for the White House during a “very big announcement” in Florida next week.

The midterms arrive at a volatile moment for the US, which emerged this year from the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic only to confront sharp economic challenges.

The Supreme Court also stripped away the constitutional right to an abortion, eliminating protections that had been in place for five decades.

And in the first national election since the January 6 insurrection, the nation’s democratic future is in question.

Some who participated in or were in the vicinity of the deadly attack are poised to win elected office on Tuesday, including House seats.

A number of Republican candidates for secretary of state, including those running in Arizona, Nevada and Michigan, have refused to accept the results of the 2020 presidential election. If they win on Tuesday, they would manage future elections in states that are often pivotal in presidential contests.

Democrats acknowledge the headwinds working against them. With only rare exceptions, the president’s party loses seats in his first midterm. The dynamic is particularly complicated by Mr Biden’s lagging approval, which left many Democrats in competitive races reluctant to appear with him.

Only 43 per cent of US adults said they approved of how Mr Biden is handling his job as president, according to an October poll by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. In the same poll, just 25 per cent said the country is heading in the right direction.

Still, Mr Biden’s allies have expressed hope that voters will reject Republicans who have contributed to an extreme political environment.

“I think what we’re seeing now is one party has a moral compass,” said Cedric Richmond, who was a senior adviser to Mr Biden in the White House and now works at the Democratic National Committee. “And one party wants a power grab.”