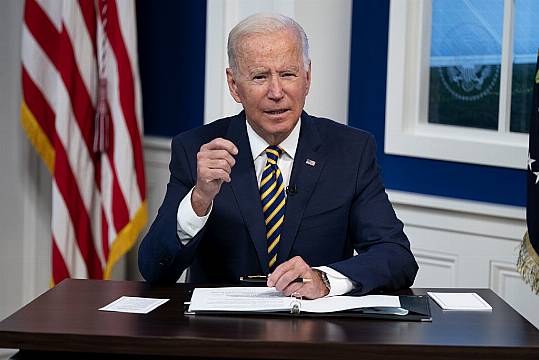

US president Joe Biden is going before the United Nations this week, eager to make the case for the world to act with haste against the coronavirus, climate change and human rights abuses.

His pitch for greater global partnership comes at a moment when allies are becoming increasingly sceptical about how much US foreign policy really has changed since Donald Trump left the White House.

Mr Biden plans to limit his time at the UN General Assembly due to coronavirus concerns. He is scheduled to meet UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres on Monday and address the assembly on Tuesday before shifting the rest of the week’s diplomacy to virtual and Washington settings.

At the 76th #UNGA session, leaders must translate words into action for the most vulnerable.

We must demonstrate that multilateralism is the only pathway to a better future for all. pic.twitter.com/o8HvJ6soBh— António Guterres (@antonioguterres) September 19, 2021

Advertisement

At a virtual Covid-19 summit he is hosting on Wednesday, leaders will be urged to step up vaccine-sharing commitments, address oxygen shortages around the globe and deal with other critical pandemic-related issues.

The president has also invited the prime ministers of Australia, India and Japan, part of a Pacific alliance, to Washington, and is expected to meet Prime Minister Boris Johnson at the White House.

Through it all, Mr Biden will be the subject of a quiet assessment by allies: Has he lived up to his campaign promise to be a better partner than Mr Trump?

Mr Biden’s chief envoy to the United Nations, ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield, offered a harmonious answer in advance of all the diplomacy: “We believe our priorities are not just American priorities, they are global priorities.”

But in the past several months, Mr Biden has found himself at odds with allies on a number of high-profile issues.

There have been noted differences over the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, the pace of Covid-19 vaccine-sharing and international travel restrictions, and the best way to respond to military and economic moves by China.

A fierce French backlash erupted in recent days after the US and UK announced they would help equip Australia with nuclear-powered submarines.

Mr Biden opened his presidency by declaring that “America is back” and pledging a more collaborative international approach.

Watch live as world leaders join @antonioguterres & special guests @BTS_twt at our SDG Moment event to inspire action for the #GlobalGoals & a better world for everyone.

Tune in here Monday, 20 September at 8am EST! pic.twitter.com/hjeWkg1X8V— United Nations (@UN) September 20, 2021

At the same time, he has focused on recalibrating national security priorities after 20 years marked by preoccupation with wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and thwarting Islamic terrorists in the Middle East and South Asia.

He has tried to make the case that the US and its democratic allies need to put greater focus on countering economic and security threats posed by China and Russia.

Mr Biden has faced resistance – and, at moments, outright anger – from allies when the White House has moved on important global decisions with what some deemed insufficient consultation.

France was livid about the submarine deal, which was designed to bolster Australian efforts to keep tabs on China’s military in the Pacific but undercuts a deal worth at least 66 billion dollars (£47 billion) for a fleet of a dozen submarines built by a French contractor.

French president Emmanuel Macron has recalled France’s ambassadors to the US and Australia for consultations in Paris.

France’s foreign minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, said Australia and the United States had both betrayed France. Mr Biden and Mr Macron are expected to speak by phone in the coming days, a French government spokesman said.

“It was really a stab in the back,” Mr Le Drian said. “It looks a lot like what Trump did.”

Biden administration and Australian officials say that France was aware of their plans, and the White House promised to “continue to be engaged in the coming days to resolve our differences”.

But Mr Biden and European allies have also been out of sync on other matters, including how quickly wealthy nations should share their coronavirus vaccine stockpiles with poorer nations.

Early on, Mr Biden resisted calls to immediately begin donating 4% to 5% of stockpiles to developing nations.

In June, the White House instead announced it was buying 500 million doses to be distributed by a World Health Organisation-backed initiative to share vaccine with low- and middle-income countries around the globe. Mr Biden is soon expected to announce additional steps to help vaccinate the world.

Allies among the Group of Seven (G7) major industrial nations have shown differing levels of comfort with Mr Biden’s calls to persuade fellow democratic leaders to present a more unified front to compete economically with Beijing.

When the leaders met this year in the UK, they agreed to work toward competing against China. But there was less unity on how adversarial a public position the group should take.

Canada, the UK and France largely endorsed Mr Biden’s position, while Germany, Italy and the European Union showed more hesitancy.

Germany, which has strong trade ties with China, has been keen to avoid a situation in which Germany, or the European Union, might be forced to choose sides between China and the United States.

Mr Biden also clashed with European leaders over his decision to stick to an August 31 deadline to end the US war in Afghanistan, which resulted in the US and Western allies leaving before all their citizens could be evacuated from Taliban rule.

UK and other allies, many of whose troops followed American forces into Afghanistan after the attacks of September 11 2001, on the United States, had urged Mr Biden to keep the American military at Kabul airport for longer, but were ultimately rebuffed by the president.

Administration officials see this week’s engagements as an important moment for the president to spell out his priorities and rally support to take on multiple crises with greater coordination.

It is also a time of political transition for some allies. Long-serving German chancellor Angela Merkel is set to leave office after Germany holds elections later this month, and Mr Macron is to face French voters in April at a moment when his political star has dimmed.