A supposedly temporary favela, or shanty town, has celebrated its centenary in Brazil.

Children queued up for a slice of creamy, blue cake at a community centre in Sao Paulo as the favela of Paraisopolis marked the occasion.

It was an unexpected milestone for a community that is still, in theory, temporary.

“People started coming (to the city) for construction jobs and settled in,” community leader Gilson Rodrigues said.

“There was no planning, not even streets.

“People started growing crops.

“It was all disorganised.

“Authorities didn’t do much, so we learned to organise ourselves.”

The favela’s centennial, which was marked on Thursday, underscores the permanence of its roots and of other communities like it, even as Brazilians in wealthier parts of town often view them as temporary and precarious.

Favelas struggle to shed that stigma as they defy simple definition, not least because they evolved over decades.

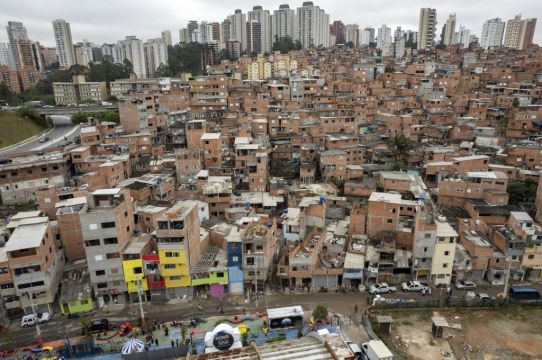

Once farmland isolated from the city, Paraisopolis is now nestled in the midst of urban sprawl.

Its population began expanding after a 1942 law froze rent prices, effectively halting private construction.

Absent action from authorities to provide housing, people sought affordable alternatives, according to Nabil Bonduki, a professor at the University of Sao Paulo’s School of Architecture and Urban Planning.

The community grew with people moving in to construct nearby Morumbi Stadium.

Now it is the city’s biggest soccer arena, home to the popular Sao Paulo Football Club — though the team’s fans are largely unaware who built it.

And Paraisopolis is Sao Paulo’s second-biggest favela, home to 43,000 people, according to the most-recent census, in 2010.

Recent, unofficial counts put its population around 100,000.

Unpainted brick homes densely pack Paraisopolis’ 3.9 square miles, an area threaded with serpentine alleys where youngsters can be found playing football or listening to loud music on weekends.