A skyscraper-sized cargo ship wedged across Egypt’s Suez Canal continues to block global shipping as at least 150 other vessels sit idle while waiting for the obstruction to be cleared, authorities said.

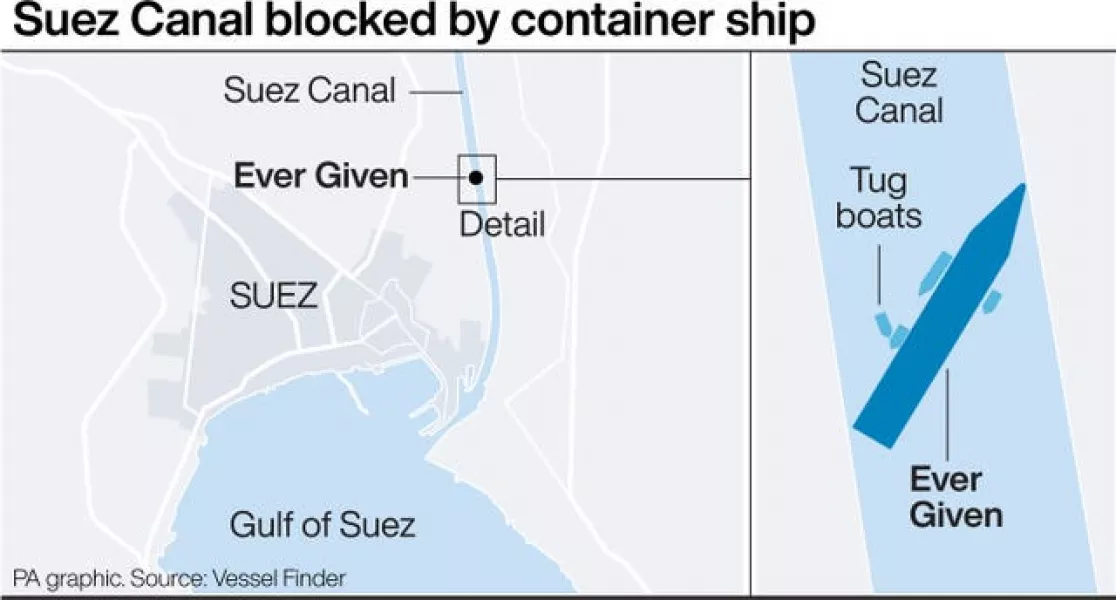

The Ever Given, a Panama-flagged ship that carries cargo between Asia and Europe, ran aground on Tuesday in the narrow, man-made canal dividing continental Africa from the Sinai Peninsula.

Efforts to free the ship using dredgers, digging and the aid of high tides are yet to push the container vessel aside.

The ship’s Japanese owner, Shoei Kisen Kaisha, offered a written apology on Thursday, saying: “We are determined to keep on working hard to resolve this situation as soon as possible. We would like to apologise to all parties affected by this incident, including the ships travelling and planning to travel through Suez Canal.”

Authorities began work again to free the vessel on Thursday morning after halting for the night, an Egyptian canal authority official said. The source said workers hoped to avoid offloading containers from the vessel as it would take days.

So far, dredgers have tried to clear silt around the massive ship. From the shore, at least one excavator dug into the canal’s sandy banks, suggesting the bow of the ship had ploughed into it.

Bernhard Schulte Shipmanagement, the company that manages the Ever Given, said the ship’s 25-member crew were safe and accounted for. The ship had two pilots from Egypt’s canal authority aboard to guide it when the grounding happened at around 7.45am on Tuesday, the company said.

Canal service provider Leth Agencies said at least 150 ships were waiting for the Ever Given to be cleared, including vessels near Port Said in the Mediterranean Sea, Port Suez in the Red Sea and those already stuck in the canal system on Egypt’s Great Bitter Lake.

Cargo ships already behind the Ever Given in the canal will be reversed south to Port Suez to free the channel, Leth Agencies said. Authorities hope to do the same to the Ever Given when they can free it.

Evergreen Marine Corp, a major Taiwan-based shipping company that operates the ship, said in a statement that the Ever Given had been overcome by strong winds as it entered the canal from the Red Sea. None of its containers had sunk.

Egyptian forecasters said high winds and a sandstorm plagued the area on Tuesday, with winds gusting as high as 30mph.

An initial report suggested the ship suffered a power blackout before the incident, something Bernhard Schulte Shipmanagement denied on Thursday.

“Initial investigations rule out any mechanical or engine failure as a cause of the grounding,” the company said.

It was the second major crash involving the Ever Given in recent years.

In 2019, the ship ran into a small ferry moored on the Elbe River in the German port of Hamburg. Authorities blamed strong wind for the collision, which severely damaged the ferry.

The Suez closure could affect oil and gas shipments to Europe from the Middle East, which rely on the canal to avoid sailing around Africa.

Shipping journal Lloyd’s List estimated that each day the canal is closed disrupts £6.6 billion of goods that should be passing through the waterway. A quarter of Suez Canal traffic comes from container ships like the Ever Given, the journal said.

The Ever Given, built in 2018 with a length of nearly 400 metres, or a quarter of a mile, and a width of 193 feet, is among the largest cargo ships in the world. It can carry 20,000 containers at a time.

It had previously been at ports in China before heading towards Rotterdam in the Netherlands.

Opened in 1869, the Suez Canal provides a crucial link for oil, natural gas and cargo. It also remains one of Egypt’s top foreign currency earners.

In 2015, the government of President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi completed a major expansion of the canal, allowing it to accommodate the world’s largest vessels. However, the Ever Given ran aground south of that new portion of the canal.

The stranding is the latest setback for mariners amid the Covid crisis, with hundreds of thousands of people having been stuck aboard vessels due to the pandemic.

Meanwhile, demands on shipping have increased, adding to the pressure on tired sailors.