Scientists in the US and Japan have found that these deep-sea microorganisms were capable of growing and dividing, even after remaining in an energy-saving state since dinosaurs roamed the planet.

The researchers said their findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, initially took them by surprise.

Study author Steven D’Hondt, of the Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, US, said: “We knew that there was life in deep sediment near the continents where there’s a lot of buried organic matter.

“But what we found was that life extends in the deep ocean from the seafloor all the way to the underlying rocky basement.”

The researchers analysed ancient sediment samples collected 10 years ago during an expedition to the South Pacific Gyre.

The samples were gathered from up to 75 metres below the seafloor and nearly 6,000 metres below the ocean’s surface, where living conditions are harsh and the nutrients that fuel the marine food chain are limited.

The sediment layers, made up of marine snow (organic material falling from the surface of the sea) and dust, were thought to have been deposited over a period from 13 to 101.5 million years ago.

The researchers also found oxygen to be present in all of the samples analysed.

Lead author Yuki Morono, from the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), said: “Our main question was whether life could exist in such a nutrient-limited environment or if this was a lifeless zone.

“And we wanted to know how long the microbes could sustain their life in a near-absence of food.”

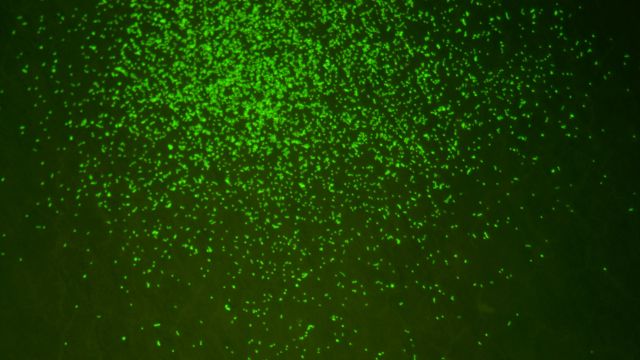

The researchers extracted the microbes from the sediments to grow in the laboratory and found some of the microorganisms responded rapidly to the incubation conditions.

Genetic analysis revealed most of these microbes to be aerobic bacteria, which require oxygen to live.

Dr Morono said: “At first I was sceptical, but we found that up to 99.1% of the microbes in sediment deposited 101.5 million years ago were still alive and were ready to eat.”

He believes that life for microbes in the sub-seafloor is “very slow” compared to life above it, so the evolutionary speed of these microbes will be slower, adding: “We want to understand how or if these ancient microbes evolved.”

Prof D’Hondt said: “In the oldest sediment we’ve drilled, with the least amount of food, there are still living organisms, and they can wake up, grow and multiply.”