Inflation in Europe slid again in June but fell too slowly to offer much relief to shoppers grumbling over price tags or to stop more interest rate hikes that will raise the cost of borrowing across the economy.

The annual rate of 5.5% was down from 6.1% in May in the 20 countries that use the euro currency, the European Union statistics agency Eurostat said on Friday.

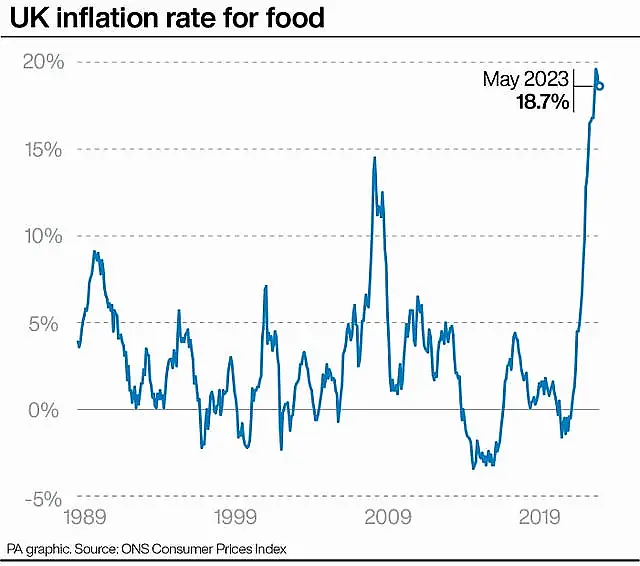

While that is a big drop from the peak of 10.6% in October, persistently high prices in the US, Europe and the United Kingdom pushed some of the world’s top central bankers to make clear they are going to keep raising rates and leave them there until inflation drops to their 2% goal considered best for the economy.

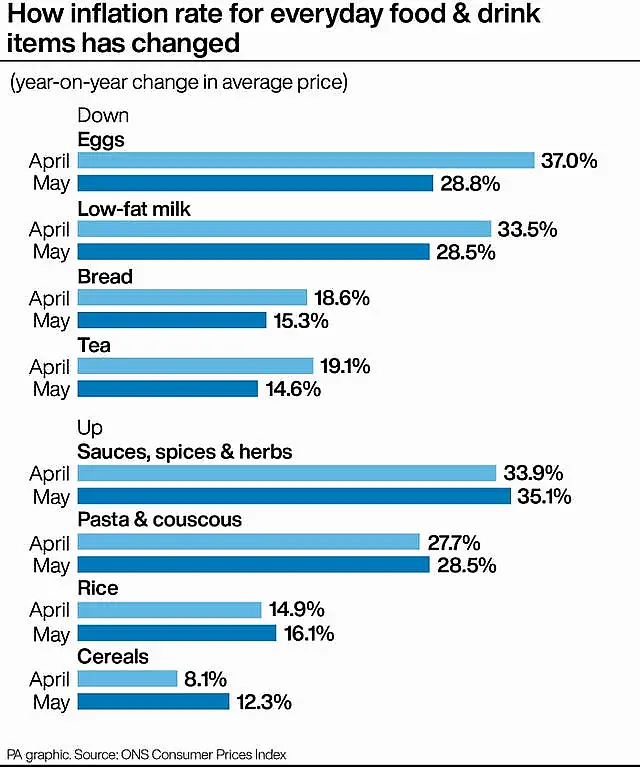

Consumers saw relief on energy prices, which dropped 5.6% after last year’s crisis, while food price inflation was up 11.7%, easing from 12.5% in May.

Core inflation, which excludes volatile food and fuel and offers a clearer picture of longer-term price pressures, rose slightly to 5.4% from 5.3% the month before.

The initial outbreak of inflation was fuelled by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which sent energy and food prices higher.

The global economy’s rebound from the Covid-19 pandemic also strained supplies of parts and raw materials.

Energy and wheat prices have subsided to pre-war levels and supply chain problems have eased – but inflation has kept snaking through other parts of the economy.

Companies selling services instead of goods — a huge swath of the economy including everything from office cleaning to haircuts to medical care — have raised their prices.

Hotels and airlines are charging summer travellers more and workers are pressing for pay raises to make up for their lost purchasing power.

The European Central Bank (ECB) — along with its peers around the world — has been rapidly raising interest rates, the chief medicine against inflation.

Increases in the ECB’s benchmark rate make it more expensive for people to borrow to buy homes and cars and businesses to acquire new office buildings and factory equipment.

That reduces demand, working to drop price levels.

One obvious impact has been in housing, with prices starting to fall after a years-long rally across Europe as homebuyers avoid asking for mortgages.

Those who have to refinance their home loans are also facing the prospect of paying thousands more than they used to.

While inflation fell rapidly as the first rate hikes took hold, going the last mile to 2% may take longer and be more difficult, central bankers say.

ECB president Christine Lagarde said this week that inflation is turning out to be more persistent than hoped.

At the bank’s annual policy conference in Sintra, Portugal, she joined US Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell and Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey in making clear that rates will go higher and stay there for as long as necessary.

The ECB has raised rates eight times in row from minus 0.5% to 3.5%.

Ms Lagarde says the bank’s rate-setting council is likely to hike at least once more at its July 27 meeting, while some members have indicated that rates could keep going up even after that.

High rates have raised concerns about their potential impact on growth, especially because the eurozone economy contracted slightly at the end of last year and the beginning of this year.

But with unemployment at a record low of 6.5%, the economy still has significant strengths.

The small dip in output in Europe was more like stagnation, Ms Lagarde said on Thursday, and the ECB’s baseline forecast “does not include a recession, but it’s part of the risk out there”.