Europe can achieve herd immunity against coronavirus within the next four months, according to the head of German pharmaceutical company BioNTech.

The company developed the first widely approved Covid-19 vaccine with US partner Pfizer.

While the exact threshold required to reach that critical level of immunisation remains a matter of debate, experts say a level above 70% would significantly disrupt transmission of coronavirus within a population.

“Europe will reach herd immunity in July, latest by August,” said Ugur Sahin, BioNTech’s chief executive.

His company’s Covid-19 vaccine makes up a large share of the doses administered in Europe and North America, where it is more commonly known as the Pfizer shot.

Mr Sahin said data from people who have received the vaccine show that the immune response gets weaker over time, and a third shot will probably be required.

Studies show the efficacy of the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine declines from 95% to about 91% after six months, he said.

“Accordingly, we need a third shot to get the vaccine protection back up to almost 100% again” Mr Sahin said.

He suggested this should be administered nine to 12 months after the first shot.

“And then I expect it will probably be necessary to get another booster every year or perhaps every 18 months again,” he said.

Concerns have been raised that existing vaccines might be less effective against new variants of the virus now emerging in different parts of the world.

Mr Sahin said BioNTech has tested its vaccine against more than 30 variants, including the now-dominant one first detected in Britain, and found the shot triggers a good immune response against almost all of them in the lab. In cases where the immune response was weaker, it remained sufficient, he said, without providing exact figures.

Asked about the new variant first detected in India, Mr Sahin said the vaccine’s effectiveness against it was still being investigated.

“But the Indian variant has mutations that we have previously investigated and against which our vaccine also works, so I am confident there, too,” he said.

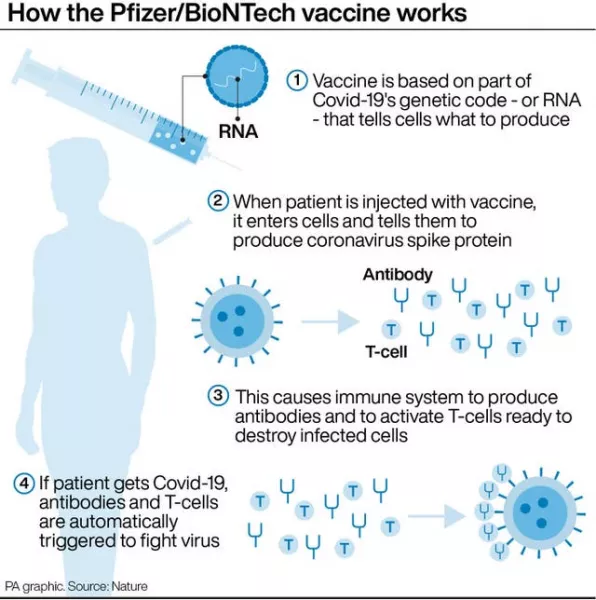

The Mainz-based company’s work developing a vaccine based on messenger RNA, or mRNA, benefited from its earlier research into pharmaceuticals to treat cancer, as tumours often try to adapt to evade the immune system, Mr Sahin said.

“The way our vaccine works is that it has two points of attack,” he explained. Along with stimulating the production of antibodies, it prompts the body’s so-called T-cells to attack the virus, he said.

“The vaccine is quite cleverly constructed, and the bulwark will hold. I’m convinced of that,” Mr Sahin said. “If the bulwark needs to be strengthened again, we’ll do so. I’m not worried.”