The head of the European Central Bank has underlined the bank’s determination to fight rampant inflation with more interest rate increases on top of record hikes.

ECB president Christine Lagarde said “our job is far from being completed” and that even a mild recession would not be enough to bring rising prices back under control.

Ms Lagarde said in a lecture at the central bank of Estonia that “we will not let high inflation become entrenched” by allowing expectations of higher prices to become baked into wages and costs, creating a spiral of ever-higher inflation.

She said central bankers must be “prepared to take the necessary decisions, however difficult, to bring inflation back down – because the consequences of letting too-high inflation become entrenched would be much worse for everyone”.

Ms Lagarde indicated that the rapid pace of increases in the bank’s benchmarks at the July 21, September 8 and October 27 meetings was not the end of the effort to snuff out inflation that has hit a record 10.7% in the 19 countries that use the euro currency, where the ECB decides monetary policy.

Ms Lagarde’s stop in Estonia follows a speech in Latvia on Thursday.

Inflation in Estonia and neighbouring Latvia and Lithuania is the highest in Europe, running at more than 20% and creating added hardship in countries where people spend a higher proportion of their income on food and fuel – 40% compared with 26% in the rest of the eurozone, according to the Latvian central bank.

The European Central Bank has raised rates by a total of two full percentage points since July, the fastest pace since the euro was launched in 1999.

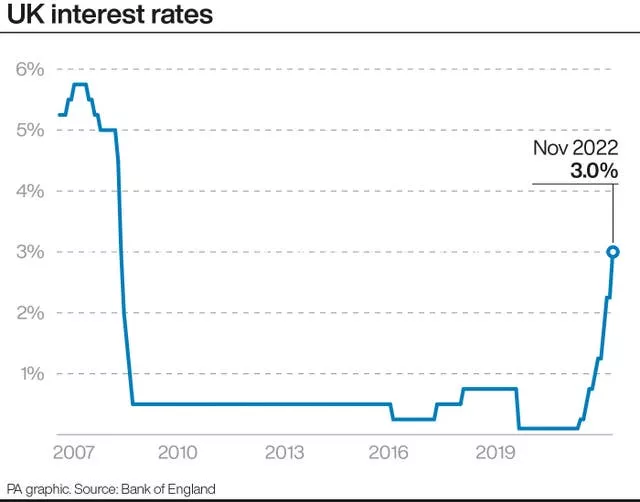

The bank’s stance has mirrored that of the US Federal Reserve, which raised rates by an outsized three-quarters of a point for the fourth straight meeting on Wednesday, and of the Bank of England, which raised rates by the same amount on Thursday.

Central banks fight inflation by raising their interest rate benchmarks, which guide the cost of credit throughout the economy.

Higher rates make credit more expensive, limiting consumption and investment and dampening demand for goods, taking upward pressure off prices.

But rate hikes also raise concerns about the impact on economic growth.

The price increases in Europe have been fuelled by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which sent natural gas prices soaring after Russia cut off most supplies to the continent.

Rebounding demand after the worst of the pandemic, along with bottlenecks in supplies of parts and materials, have also played a role.

A reordering of supply chains, with some companies seeking to locate supply and production in countries that are considered less subject to disruption through war or politics, can also push prices higher as security rather than low cost takes precedence.

Inflation has robbed consumers of spending power and led many economists to predict a recession at the end of this year and beginning of next year.

Ms Lagarde said that the “risk of recession has increased” despite third-quarter growth that came in higher than expected at 0.2% over the three months prior.

Yet slowing growth would not be enough by itself to bring down rising prices through weaker demand, she said, citing experience from past recessions that “suggests that we should not expect slowing growth to make a significant dent in inflation, at least not in the near term”.