Far-right parties have made such big gains at the European Union parliamentary elections that they dealt stunning defeats to two of the bloc’s most important leaders: French president Emmanuel Macron and German chancellor Olaf Scholz.

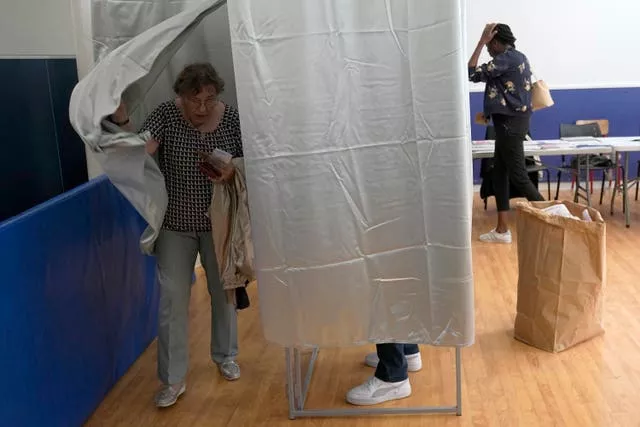

In France, the National Rally party of Marine Le Pen dominated the polls to such an extent that Mr Macron immediately dissolved the national parliament and called for new elections, a massive political risk since his party could suffer more losses, hobbling the rest of his presidential term that ends in 2027.

In Germany, Mr Scholz suffered such an ignominious fate that his long-established Social Democratic party fell behind the extreme-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), which surged into second place.

Adding insult to injury, the National Rally’s lead candidate, Jordan Bardella, all of 28 years old, immediately took on a presidential tone with his victory speech in Paris, opening with “My dear compatriots” and adding “the French people have given their verdict, and it’s final”.

Mr Macron acknowledged the thud of defeat.

“I’ve heard your message, your concerns, and I won’t leave them unanswered,” he said, adding that calling a snap election only underscored his democratic credentials.

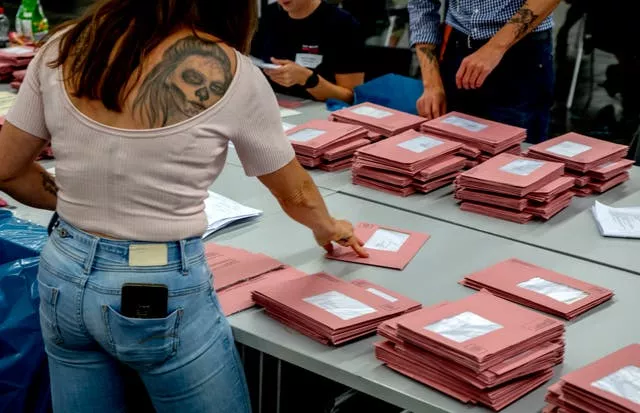

The four-day polls in the 27 EU countries were the world’s second-biggest exercise in democracy, behind India’s recent election.

At the end, the rise of the far right was even more stunning than many analysts predicted.

The French National Rally stood at just over 30 per cent, or about twice as much as Mr Macron’s pro-European centrist Renew party that is projected to reach around 15 per cent.

In Germany, the most populous nation in the 27-member bloc, projections indicated that the AfD overcame a string of scandals involving its top candidate to rise to 16.5 per cent, up from 11 per cent in 2019.

In comparison, the combined result for the three parties in the German governing coalition barely topped 30 per cent.

Overall across the EU, two mainstream and pro-European groups, the Christian Democrats and the Socialists, remained the dominant forces.

The gains of the far right came at the expense of the Greens, who were expected to lose about 20 seats and fall back to sixth position in the legislature.

For decades, the European Union, which has its roots in the defeat of Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, confined the hard right to the political fringes.

With its strong showing in these elections, the far right could now become a major player in policies ranging from migration to security and climate.

The Greens were predicted to fall from 20 per cent to 12 per cent in Germany, a traditional bulwark for environmentalists, with more losses expected in France and several other EU nations.

Their defeat could well have an impact on the EU’s overall climate change policies, still the most progressive around the globe.

The centre-right Christian Democratic bloc of EU Commission president Ursula von der Leyen, which already weakened its green credentials ahead of the polls, dominated in Germany with almost 30 per cent, easily beating Mr Scholz’s Social Democrats, who fell to 14 per cent, even behind the AfD.

“What you have already set as a trend is all the better – strongest force, stable, in difficult times and by a distance,” Ms von der Leyen told her German supporters by video link from Brussels.

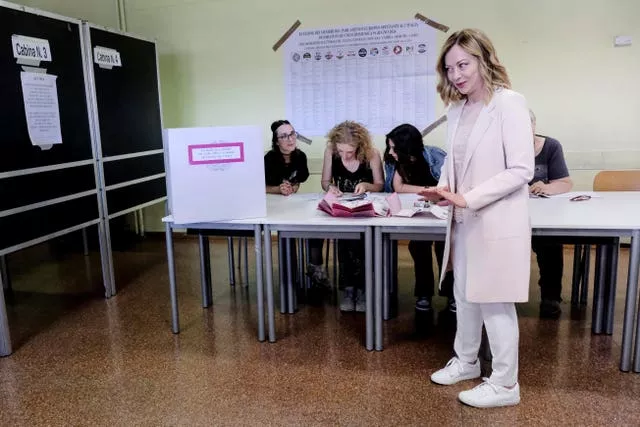

As well as France, the hard right, which focused its campaign on migration and crime, was expected to make significant gains in Italy, where prime minister Giorgia Meloni was tipped to consolidate her power.

Voting continued in Italy until late in the evening and many of the 27 member states have not yet released any projections.

Nonetheless, data already released confirmed earlier predictions: the EU’s massive exercise in democracy is expected to shift the bloc to the right and redirect its future.

With the centre losing seats to hard-right parties, the EU could find it harder to pass legislation and decision-making could at times be paralysed in the world’s biggest trading bloc.

EU legislators, who serve a five-year term in the 720-seat parliament, have a say in issues from financial rules to climate and agriculture policy.

They approve the EU budget, which bankrolls priorities including infrastructure projects, farm subsidies and aid delivered to Ukraine.

And they hold a veto over appointments to the powerful EU commission.

These elections come at a testing time for voter confidence in a bloc of some 450 million people.

Over the last five years, the EU has been shaken by the coronavirus pandemic, an economic slump and an energy crisis fuelled by the biggest land conflict in Europe since the Second World War.

But political campaigning often focuses on issues of concern in individual countries rather than on broader European interests.

The voting marathon began in the Netherlands on Thursday, where an unofficial exit poll suggested that the anti-migrant hard-right party of Geert Wilders would make important gains, even though a coalition of pro-European parties has probably pushed it into second place.

Casting his vote in the Flanders region, Belgian prime minister Alexander De Croo, whose country holds the EU’s rotating presidency until the end of the month, warned that Europe was “more under pressure than ever”.

Since the last EU election in 2019, populist or far-right parties now lead governments in three nations – Hungary, Slovakia and Italy – and are part of ruling coalitions in others, including Sweden, Finland and, soon, the Netherlands.

Polls give the populists an advantage in France, Belgium, Austria and Italy.

“Right is good,” Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban, who leads a stridently nationalist and anti-migrant government, told reporters after casting his ballot.

“To go right is always good. Go right!”

After the election comes a period of horse-trading, as political parties reconsider their places in the continent-wide alliances that run the European legislature.

The biggest political group – the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) – has moved further right during the present elections on issues such as security, climate and migration.

Among the most watched questions is whether the Brothers of Italy – the governing party of populist Ms Meloni, which has neo-fascist roots – stays in the more hard-line European Conservatives and Reformists group or becomes part of a new hard right group that could form in the wake of the elections.

Ms Meloni also has the option to work with the EPP.

A more worrying scenario for pro-European parties would be if the ECR joins forces with Ms Le Pen’s Identity and Democracy group to consolidate hard-right influence.

The second-biggest group – the centre-left Socialists and Democrats – and the Greens refuse to align themselves with the ECR.

Questions also remain over which group Mr Orban’s ruling Fidesz party might join.

It was previously part of the EPP but was forced out in 2021 due to conflicts over its interests and values.

The far-right Alternative for Germany was kicked out of the Identity and Democracy group following a string of scandals surrounding its two lead candidates for the European Parliament.

The election also ushers in a period of uncertainty as new leaders are chosen for the European institutions.

While legislators are jostling over places in alliances, governments will be competing to secure top EU jobs for their national officials.

Chief among them is the presidency of the powerful executive branch, the European Commission, which proposes laws and watches to ensure they are respected.

The commission also controls the EU’s purse strings, manages trade and is Europe’s competition watchdog.

Other plum posts are those of European Council president, who chairs summits of presidents and prime ministers, and EU foreign policy chief, the bloc’s top diplomat.