Hillsborough families have vowed to continue campaigning for a law which they describe as a “legacy” to the victims of the disaster, after the British government stopped short of introducing the legislation.

On Wednesday, ministers apologised for delays as they published a response to former bishop of Liverpool the Right Rev James Jones’s report into the experiences of families of the 97 victims of the tragedy, which happened at the 1989 FA Cup semi-final at the Sheffield Wednesday stadium.

The British government said it had signed up to a Hillsborough Charter, pledging to place the public interest above its own reputation, but said a “Hillsborough Law” incorporating a legal duty of candour was not necessary.

Campaigner Margaret Aspinall, whose 18-year-old son James Aspinall was one of the victims of the tragedy, said: “To me, it’s like giving a child a packet of crisps but when you open it there’s nothing in it.

“It’s as simple as that. To me that definitely does not go far enough.

“We will be arguing for a Hillsborough Law, that’s the most important thing to me.”

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak told the Commons he was “profoundly sorry” for what the Hillsborough families had been through and hoped to meet them in the new year.

Home Secretary James Cleverly and Justice Secretary Alex Chalk said they were “deeply sorry” for the delay in responding to Mr Jones’s recommendations, published in 2017, and acknowledged it had taken “too long, compounding the agony of the Hillsborough families and survivors”.

Jenni Hicks, mother of Hillsborough victims Sarah, 19, and Vicki, 15, said: “I think we’re way past apologies really, we passed apologies a long time ago.

“It was frustrating to wait this long and, reading the report, I don’t know what on earth’s taken them six years to respond because a lot of the things they’re talking about still need a lot of consultations, still haven’t been agreed.”

In his report, Mr Jones called for the British government to give “full consideration” to a “Hillsborough Law” or Public Authority (Accountability) Bill, which would include a legal duty of candour on public authorities and officials to tell the truth and proactively co-operate with official investigations and inquiries.

But the response stated the British government was “not aware” of any gaps in legislation or clarifications needed that would further encourage a culture of candour among public servants in law.

It is understood the British government believes that adopting the duty of candour would risk “creating conflict and confusion” because of the framework of duties and obligations already developed since the disaster.

Deanna Matthews, whose uncle Brian died at Hillsborough, said she believed the Government response was “misguided”.

She said: “It’s quite clear to see that the legislation that we would want to be introduced by the Hillsborough Law doesn’t exist in the format that we would propose that it needs to be.

“Yes, there are various different duties over various different departments or public sectors but there’s not one unifying piece of legislation that brings it all together neatly under one header.”

Ms Matthews’ mother, Debbie, said they would not give up the campaign.

She added: “If we do get the Hillsborough Law that’s going to be the legacy to our loved ones. It’s not going to help us but hopefully it will help other people who find themselves in a situation where they’re up against the state.”

In its report, the Government said the families and survivors were “entirely justified” in their frustration with the evasiveness they experienced from public officials.

But it said much had changed in terms of expectations and requirements on public officials since 1989.

It said that “continuing to drive and encourage a culture of candour among public servants” was essential and an important part of the Hillsborough Charter, which Deputy prime minister Oliver Dowden had signed on behalf of the British government.

By signing the charter for families bereaved through public tragedy, proposed by Mr Jones, leaders of public bodies commit to place the public interest above their own reputations, approach forms of public scrutiny – including public inquiries and inquests – with candour, and avoid seeking to defend the indefensible.

The British government response also states that it will consult on expanding the provision of legal aid for inquests following public disasters.

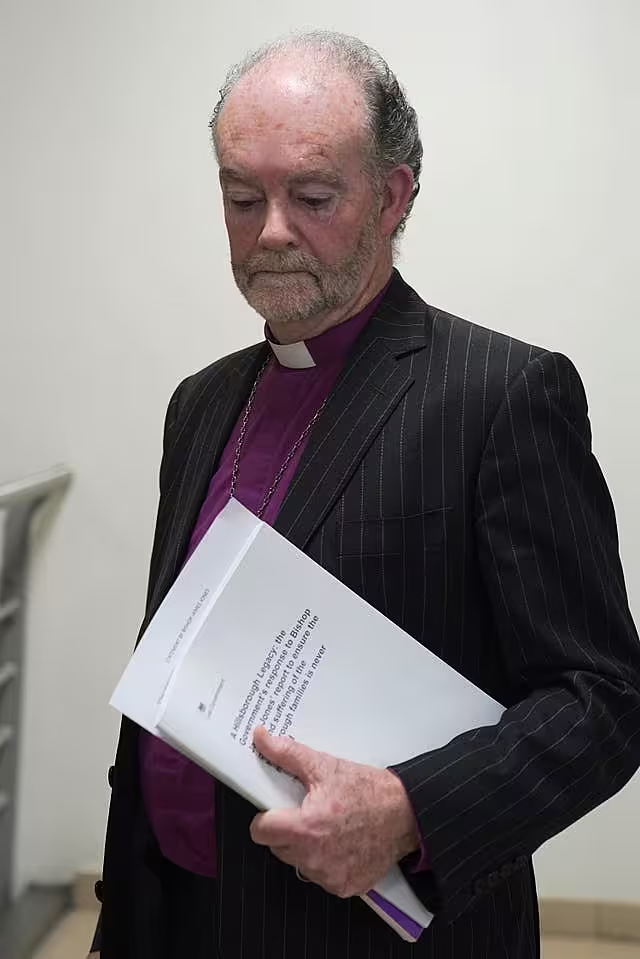

Mr Jones, who was with Hillsborough families in Liverpool when the Government response was published, said it was a “serious and substantial response”.

He said: “The purpose of my report was to ‘ensure that the pain and suffering of the Hillsborough families is not repeated’. I say to the government and to the families that this will be the test of these measures.

“The government has made significant changes and I will continue to press for further action.”

Inquests into the deaths at the match, played between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest on April 15 1989, concluded in 2016 and found the victims were unlawfully killed and errors by the police and ambulance service caused or contributed to their deaths.

The match commander on the day, David Duckenfield, was charged with gross negligence manslaughter in 2017 but he was cleared in 2019 at a retrial, after the jury in his first trial was unable to reach a verdict.

In 2021, retired officers Donald Denton and Alan Foster and former force solicitor Peter Metcalf, who were accused of amending statements to minimise the blame on South Yorkshire Police, were acquitted of perverting the course of justice after a judge ruled there was no case to answer.