Three days after its August 6 1945, bombing of Hiroshima, the United States dropped a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki.

Japan surrendered on August 15, ending the Second World War and, more broadly, its aggression toward Asian neighbours that had lasted nearly half a century.

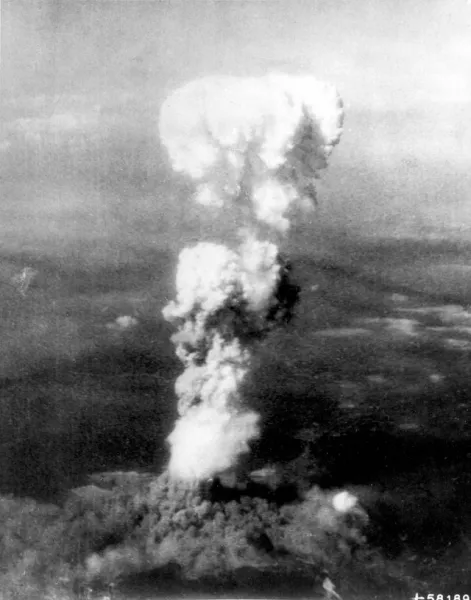

Here is a look at that day in Hiroshima 75 years ago.

Hiroshima was a major Japanese military hub with factories, military bases and ammunition facilities.

Historians say the United States picked it as a suitable target because of its size and landscape, and carefully avoided fire bombing the city ahead of time so American officials could accurately assess the impact of the atomic attack.

The United States said the bombings hastened Japan’s surrender and prevented the need for a US invasion of Japan.

Some historians today say Japan was already close to surrendering, but there is still debate in the US.

At 8.15am, the US B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped a four-ton Little Boy uranium bomb from a height of 9,600 metres (31,500 feet) on the city centre, targeting the Aioi Bridge.

The bomb exploded 43 seconds later, 600 metres (2,000 feet) above the ground.

Seconds after the detonation, the estimated temperature was 3,000-4,000C at ground zero.

Almost everything within 1.2 miles of ground zero was destroyed by the blast and heat rays.

Within one hour, a “black rain” of highly radioactive particles started falling on the city, causing additional radiation exposure.

An estimated 140,000 people, including those with radiation-related injuries and illnesses, died up to December 31, 1945.

That was 40% of Hiroshima’s population of 350,000 before the attack.

Everyone within a radius of 500 metres (1,600 feet) from ground zero died that day.

To date, the total death toll, including those who died from radiation-related cancers, is about 300,000.

Hiroshima today has 1.2 million residents.

Many people exposed to radiation developed symptoms such as vomiting and hair loss.

Most of those with severe radiation symptoms died within three to six weeks.

Others who lived beyond that developed health problems related to burns and radiation-induced cancers and other illnesses.

Survivors have a higher risk of developing cataracts and cancer.

About 136,700 people certified as “hibakusha”, as victims are called, under a government support program are still alive and entitled to regular free health checkups and treatment.

Health monitoring of second-generation hibakusha began recently. Japan’s government provided no support for victims until a law was finally enacted in 1957 under pressure from them.

Origami paper cranes can be seen throughout the city.

They became a symbol of peace because of a 12-year-old bomb survivor, Sadako Sasaki, who, while battling leukaemia, folded paper cranes using medicine wrappers after hearing an old Japanese story that those who fold a thousand cranes are granted one wish.

Sadako developed leukaemia 10 years after her exposure to radiation at the age of two, and died three months after she started the project.

Former US President Barack Obama brought four paper cranes that he folded himself when he visited Hiroshima in May 2016, becoming the first serving American leader to visit.

Mr Obama’s cranes are now displayed at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.