India opened vaccinations to all adults on Saturday, launching a huge inoculation effort in the hope of taming a monstrous spike in Covid-19 infections.

The world’s largest maker of vaccines was still short of critical supplies, the result of lagging manufacturing and raw material shortages that delayed the rollout in several states.

And even in places where the shots were in stock, the country’s wide economic disparities made access to the vaccine inconsistent.

Only a fraction of India’s 1.4 billion people will be able to afford the prices charged by private hospitals for the shot, experts said, meaning that states will be saddled with immunising the 600 million Indian adults younger than 45, while the federal government gives shots to 300 million healthcare and frontline workers and people older than 45.

So far, government vaccines have been free and private hospitals have been permitted to sell shots at a price capped at 250 rupees, or about £2.40.

That practice will now change and prices for state governments and private hospitals will be determined by vaccine companies.

Some states might not be able to provide vaccines for free since they are paying twice as much as the federal government for the same shot, and prices at private hospitals could rise.

Since state governments and private players compete for shots in the same marketplace, and states pay less for the doses, vaccine-makers can reap more profit by selling to the private sector, said Chandrakant Lahariya, a health policy expert.

That cost can then be passed on to people receiving the shots, increasing inequity.

“There is no logic that two different governments should be paying two prices,” he said.

Concerns that pricing issues could deepen inequities are only the most recent hitch in India’s sluggish immunisation efforts.

Less than 2% of the population has been fully immunised against Covid-19 and about 10% have received a single dose.

Immunisation rates have also fallen. The average number of shots per day dipped from over 3.6 million in early April to fewer than 2.5 million now.

In the worst-hit state of Maharashtra, the health minister promised free vaccines for those aged 18 to 44, but he also acknowledged that the shortage of doses meant immunisation would not start as planned on Saturday.

India thought the worst was over when cases ebbed in September. But mass gatherings such as political rallies and religious events were allowed to continue, and relaxed attitudes on the risks fuelled a major humanitarian crisis, according to health experts.

New variants of coronavirus have partly led the surge. Deaths officially surpassed 200,000 this week, and the true death toll is believed to be far higher.

The country’s shortage of shots has global implications because, in addition to its own inoculation efforts, India has promised to ship vaccines abroad as part of a United Nations’ vaccine-sharing programme that is dependent on its supply.

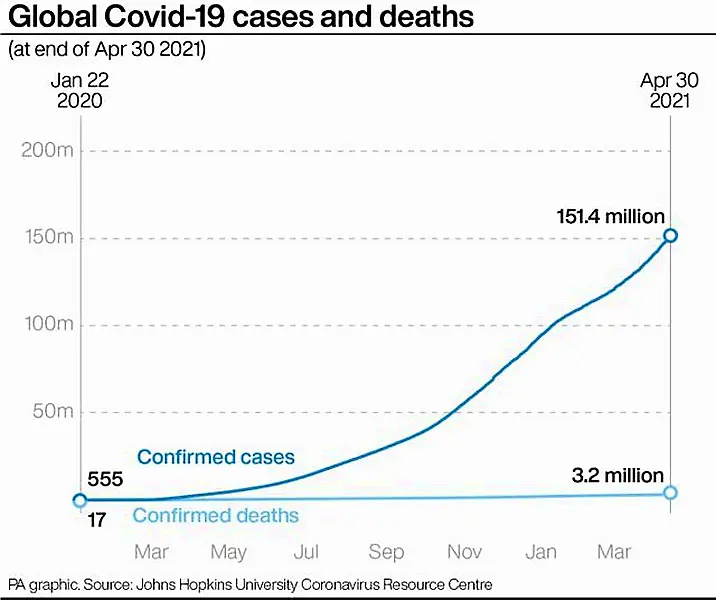

Some experts warned that conducting a massive inoculation effort now could worsen the surge in a country that is second only to the United States in its number of infections – more than 19.1 million.

“There’s ample evidence that having people wait in a long, crowded, disorderly queue could itself be a source of infection,” said Dr Bharat Pankhania, a senior clinical lecturer at the University of Exeter specialising in infectious diseases.