India’s top court has put the country’s colonial-era sedition law on hold.

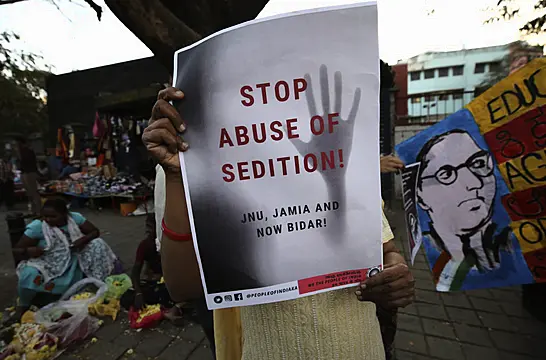

Critics said the government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi was increasingly using it to silence criticism and dissent.

The Supreme Court order asked the Indian government and state authorities to refrain from registering fresh cases under the harsh law while it was under review and allowed accused people detained under it to seek bail from courts.

“It will be appropriate not to use this provision of law til further re-examination is over,” the three-judge bench headed by India’s Chief Justice NV Ramana said in New Delhi.

The order also put on hold all pending cases, appeals and proceedings with respect to charges framed under the 152-year-old law.

India’s sedition law, like its equivalent in other formerly British-ruled countries, offers a legal framework to categorise a citizen as a threat to the state.

Globally, it is increasingly viewed as a draconian law and was revoked in the United Kingdom in 2010.

Its use to silence critics in India is not new.

During previous governments, people were charged with sedition for liking a Facebook post critical of the administration, criticising a yoga guru, cheering a rival cricket team, drawing political cartoons, and not standing up in a cinema for the national anthem, which is often played before films.

But under Mr Modi, critics say, India is growing notoriously intolerant, its crackdown on critics unprecedented in scale.

Mr Modi’s Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party government has increasingly brandished the law to silence critics, intellectuals, human rights activists, filmmakers, students and journalists, with police arguing that words or actions of dissent make them a threat to national security.

Senior counsel Kapil Sibal told the court that at least 13,000 people were in jail under the law.

Critics say the long and slow judicial process becomes punishment for the accused seeking justice.

India’s notoriously slow criminal justice system ensures that the movement and speech of the accused are severely hamstrung as long as cases remain pending.

While charged, people cannot obtain passports or government jobs, and must show up to court as required.