A total of 6 billion dollars (£4.84bn) of Iranian assets once frozen in South Korea is now in Qatar, a key element for a planned swap of prisoners – including a British citizen – between Tehran and the US, an Iranian official said.

Nasser Kanaani made the comment during a news conference on state television but the feed cut immediately after his remarks without explanation.

“The issue of swap of prisoners will be done on this day and five prisoners, citizens of the Islamic Republic, will be released from the prisons in the US,” Mr Kanaani said. “Five imprisoned citizens who were in Iran will be given to the US side reciprocally, based on their will. We expect these two issues fully take place based on agreement.”

He said two of the Iranian prisoners will stay in the US.

The announcement by Mr Kanaani comes weeks after Iran said that five Iranian-Americans are under house arrest as part of a confidence-building move while Seoul allowed the frozen assets, held in South Korean currency, to be converted into euros. That money was then sent to Qatar, an interlocutor between Tehran and Washington in the negotiations.

One of the five prisoners is Morad Tahbaz, a British-American conservationist of Iranian descent who was arrested in 2018 and received a 10-year sentence for alleged spying.

The swap unfolded amid a major American military build-up in the Persian Gulf, with the possibility of US troops boarding and guarding commercial ships in the Strait of Hormuz, through which 20% of all oil shipments pass.

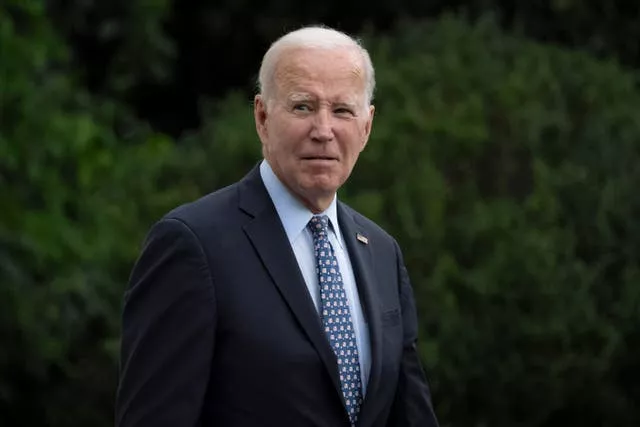

The deal has opened President Joe Biden to fresh criticism from Republicans and others who say that the administration is helping boost the Iranian economy at a time when Iran poses a growing threat to US troops and Middle East allies.

On the US side, Washington has said the planned swap includes Siamak Namazi, who was detained in 2015 and later sentenced to 10 years in prison on internationally criticised spying charges, Emad Sharghi, a venture capitalist sentenced to 10 years, as well as Mr Tahbaz.

US officials have so far declined to identify the fourth and fifth prisoner.

The five prisoners Iran has said it seeks are mostly held over allegedly trying to export material to Iran.

The final dollar amount from Seoul could be anywhere between 6 billion to 7 billion, depending on exchange rates. The cash represents money South Korea owed Iran — but had not yet paid — for oil purchased before the Trump administration imposed sanctions on such transactions in 2019.

The US maintains that, once in Qatar, the money will be held in restricted accounts and will only be able to be used for humanitarian goods, such as medicine and food. Those transactions are allowed under American sanctions targeting the Islamic Republic over its advancing nuclear programme.

Iranian government officials have largely concurred with that explanation, though some hard-liners have insisted, without providing evidence, that there would be no restrictions on how Tehran spends the money.

Iran and the US have a history of prisoner swaps dating back to the 1979 US Embassy takeover and hostage crisis following the Islamic Revolution.

Their most recent major exchange happened in 2016, when Iran came to a deal with world powers to restrict its nuclear programme in return for an easing of sanctions.

Four American captives, including Washington Post journalist Jason Rezaian, flew home from Iran at the time, and several Iranians in the US won their freedom. That same day, President Barack Obama’s administration airlifted 400 million dollars in cash to Tehran.

Iran has received international criticism over its targeting of people with dual citizenship. The West accuses Iran of using foreign prisoners as bargaining chips, an allegation Tehran rejects.

Negotiations over a major prisoner swap faltered after then-president Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew America from the nuclear deal in 2018. From the following year on, a series of attacks and ship seizures attributed to Iran have raised tensions.

Meanwhile, Iran’s nuclear programme now enriches closer than ever to weapons-grade levels.

While the head of the United Nations’ nuclear watchdog has warned that Iran now has enough enriched uranium to produce “several” bombs, months more would likely be needed to build a weapon and potentially miniaturise it to put it on a missile — if Iran decided to pursue one.

The US intelligence community has maintained its assessment that Iran is not pursuing an atomic bomb.