Japan’s prime minister has expressed sympathy for the suffering of Korean forced labourers during Japan’s colonial rule.

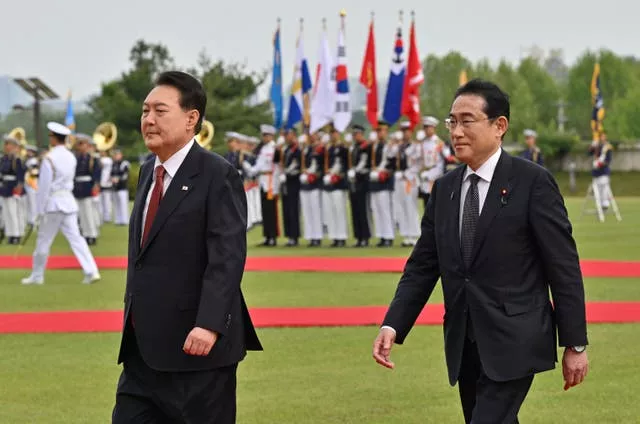

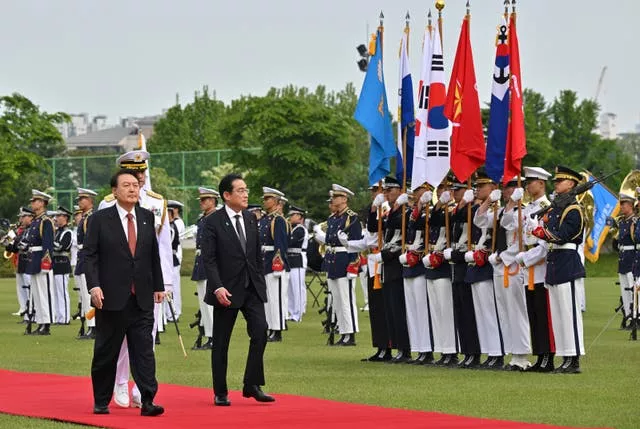

Fumio Kishida was speaking as he and his South Korean counterpart renewed their resolve to overcome historical grievances and strengthen co-operation in the face of shared challenges such as North Korea’s nuclear programme.

The comments by Mr Kishida during his second summit in less than two months with South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol are closely watched in Seoul.

Mr Yoon has faced domestic criticism that he had pre-emptively made concessions to Tokyo without getting corresponding steps in return.

Mr Kishida’s statement, which avoided a new, direct apology over the colonisation but still sympathised with the Korean victims, suggests he felt pressure to say something to maintain momentum for improved ties.

“And personally, I have strong pain in my heart as I think of the extreme difficulty and sorrow that many people had to suffer under the severe environment in those days,” Mr Kishida told a joint news conference with Mr Yoon, referring to Japan’s 1910-1945 colonial rule of the Korean Peninsula.

“Japan and South Korea share various history and development, and I believe it is my responsibility as prime minister of Japan to co-operate with President Yoon and the South Korean side as we follow through the effort of our predecessors who have also overcome the difficult times,” he said.

Mr Kishida arrived in South Korea earlier on Sunday for a two-day visit, which reciprocates a mid-March trip to Tokyo by Mr Yoon and marks the first exchange of visits between the leaders of the Asian neighbours in 12 years.

The back-to-back summits were largely meant to resolve the countries’ bitter disputes caused by the 2018 court rulings in South Korea that ordered two Japanese companies to financially compensate some of their aging former Korean employees for colonial-era forced labour.

Japan has refused to abide by the verdicts, arguing that all compensation issues were already settled when the two countries normalised ties in 1965.

The wrangling led to the countries downgrading each other’s trade status and Seoul’s previous liberal government threatening to spike a military intelligence-sharing pact.

The strained South Korea-Japan ties complicated US efforts to build a stronger regional alliance to better cope with rising Chinese influence and North Korean nuclear threats.

In March, however, Mr Yoon’s conservative government took a major step towards mending the ties by announcing it would use local funds to compensate the forced labour victims without demanding contributions from Japanese companies.

Later in March, Mr Yoon travelled to Tokyo to meet Mr Kishida, and the two agreed to resume leadership-level visits and other talks. Their governments have since taken steps to withdraw their economic retaliatory steps against each other.

Mr Yoon’s push, however, drew a strong backlash from some of the forced labour victims and his liberal rivals at home, who have demanded direct compensation from the Japanese companies.

Mr Yoon has defended his move, saying greater co-operation with Japan is required to jointly tackle North Korea’s advancing nuclear programme, the intensifying US-China strategic rivalry and global supply chain challenges.

“We should stay away from a thinking that we must not make a step forward for our future co-operation because our history issues aren’t settled completely,” Mr Yoon said on Sunday.

Mr Kishida reaffirmed his government upholds the positions of previous Japanese administrations, including the landmark 1998 joint declaration by Tokyo and Seoul on improving ties, but did not make a new apology.

In that declaration, then-Japanese prime minister Keizo Obuchi said “I feel acute remorse and offer an apology from my heart” over the colonial rule.

Japanese governments have expressed remorse or apologies over the colonial period numerous times. But some Japanese officials and politicians have occasionally made comments that have been accused of whitewashing Tokyo’s wartime aggressions, prompting Seoul to urge Tokyo to make new, more sincere apologies.

Ahead of his summit with Mr Yoon, Mr Kishida and his wife visited the national cemetery in Seoul, where they burned incense and paid a silent tribute before a memorial.

Buried or honoured in the cemetery are mostly Korean War dead, but include Korean independence fighters during the period of Japanese rule. Mr Kishida was the first Japanese leader to visit the place in 12 years.

“Kishida’s comments about Koreans who suffered under Japanese colonialism may be criticised for not being more specific about historical perpetrators and more apologetic towards historical victims,” said Leif-Eric Easley, a professor at Ewha University in Seoul. “But Kishida did visit South Korea’s national cemetery and said that his heartfelt views, respect for the past, and recognition of current global challenges produce a sense of responsibility for improving Seoul-Tokyo relations.”

Mr Yoon said talks among Seoul, Tokyo and Washington are under way to implement their earlier agreement on sharing information on North Korean missile launches. Mr Yoon said he and Mr Kishida reaffirmed that North Korea’s nuclear and missile programmes pose a grave threat to the two countries and the rest of the world.

In late April, Mr Yoon made a state visit to the United States and agreed with President Joe Biden to reinforce deterrence capabilities against North Korea’s nuclear threats.

During a joint news conference, Mr Biden thanked Mr Yoon “for your political courage and personal commitment to diplomacy with Japan”.