A judge is set to reconsider whether a grandmother in her 50s, who was left brain-damaged and paralysed from the neck down as a result of contracting Covid-19, should be allowed to die after relatives won a Court of Appeal fight in the UK.

The woman’s adult children had mounted a challenge after a judge in the UK Court of Protection ruled earlier this year that she should be allowed to die.

Appeal judges have ruled in their favour and said the case should be reconsidered at another Court of Protection hearing.

One of woman’s children said he “almost cried” when he heard the result of the appeal.

Mr Justice Hayden initially considered evidence at a trial in the Court of Protection, where judges oversee hearings centred on adults who lack the mental capacity to make decisions, in London and concluded that life-support treatment should stop by the end of October.

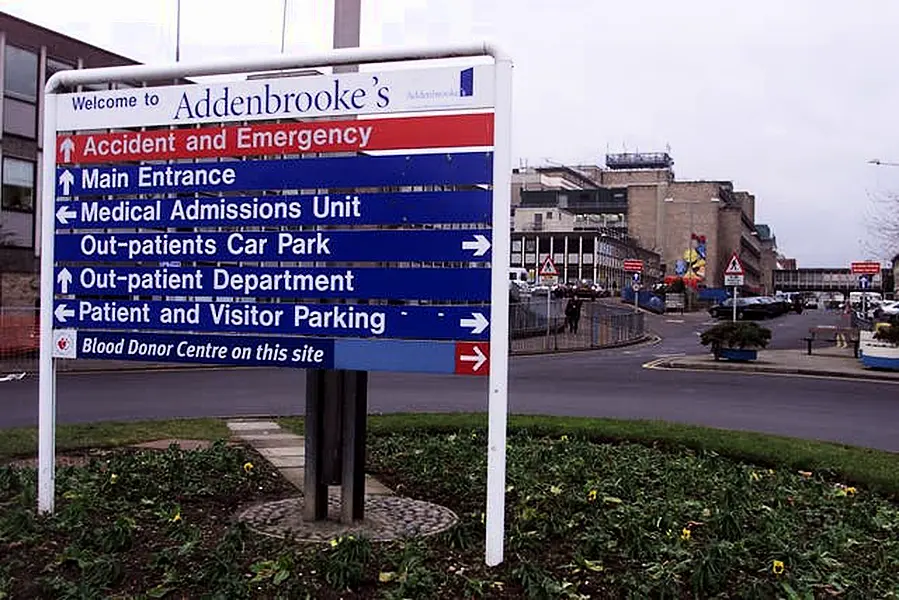

Specialists treating the woman, whom doctors have described as the most complicated Covid patient in the world, at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge had said life-support treatment should end.

The woman’s relatives had disagreed and said she should be given more time.

Sir Andrew McFarlane, the most senior Court of Protection judge in England and Wales, Lord Justice Moylan and Sir Nicholas Patten had heard argument at a Court of Appeal hearing in London in early November.

Appeal judges raised concern, in a ruling published on Thursday, about a visit Mr Justice Hayden had made to see the woman in hospital.

They said the judge might have gained insight into the woman’s condition.

But they suggested that her relatives had not had an opportunity to comment on what the judge might have learned.

Lord Justice Moylan said, in the appeal ruling, that what happened when Mr Justice Hayden saw the woman in hospital could have “more than one interpretation”.

He said evidence suggested that she might have given Mr Justice Hayden “some insight into her wishes”.

“If that is right, the judge’s decision is undermined for two reasons,” said Lord Justice Moylan.

“First, it is strongly arguable that the judge was not equipped properly to gain any insight into (her) wishes and feelings from his visit. Her complex medical situation meant that he was not qualified to make any such assessment.

“If the visit was used by the judge for this purpose, the validity of that assessment might well require further evidence or, at least, further submissions.

“Secondly, in order to ensure procedural fairness, the parties needed to be informed about this and given an opportunity to make submissions.”

One of the woman’s children said after the ruling: “I almost cried when I found out. It’s like a ton of bricks has been lifted off me.

“We are now preparing for the next hearing – we are preparing for everything.”

Doctors treating the woman had told Mr Justice Hayden how they thought that her life expectancy could be measured in months.

They said moving her to a palliative care regime would enable her to die peacefully and without distress.

Mr Justice Hayden said it was the first time a judge had considered an end-of-life case as a result of Covid-19.

He heard how the woman, who was overweight and had underlying health problems, went into hospital with symptoms of Covid-19 late in 2020.

Barrister Katie Gollop QC, who represented hospital bosses, said the woman’s case appeared to be “unique”.

She said the woman was “almost entirely paralysed” and had “severe” cognitive impairment.

One specialist said the woman had complications not “described” in the UK before.

Mr Justice Hayden ruled that the woman could not be identified in media reports.

Lawyers representing the woman’s relatives said a different judge would reconsider the case in the Court of Protection.

The woman’s relatives had not been represented by lawyers at the Court of Protection before Mr Justice Hayden.

They had legal representation at the appeal hearing.

Edward Devereux QC, who led their legal team and worked for free, said: “This case, perhaps, shows the vital importance of proper and specialist legal representation in cases involving the withdrawal of life sustaining treatment.

“It is perhaps unfair for a family member who cannot afford a lawyer, and who might have come almost straight from a hospital bedside, to stand alone directly before a judge to argue that a hospital should not remove life sustaining treatment from a person that they love.”

Sir Andrew said there had been “a lack of clarity over the purpose” of Mr Justice Hayden’s visit to the hospital.

He said the case indicated that there was a pressing need for “workable guidance” relating to judges’ visits to patients at the centre of Court of Protection hearings.