President Michel Aoun left Lebanon’s presidential palace, marking the end of his six-year term without a replacement, leaving the small nation in a political vacuum that is likely to worsen its historic economic meltdown.

As Mr Aoun’s term ends, the country is being run by a caretaker government after prime minister-designate Najib Mikati failed to form a new Cabinet following May 15 parliamentary elections.

Mr Aoun and his supporters warn that such a government does not have full power to run the country, saying that weeks of “constitutional chaos” lay ahead.

In a speech outside the palace, Mr Aoun told thousands of supporters that he has accepted the resignation of Mr Mikati’s government.

The move is likely to further deprive the caretaker administration of legitimacy and worsen existing political tensions in the country.

Mr Mikati responded shortly afterward with a statement from his office saying that his government will continue to perform its duties in accordance with the constitution.

Many fear that an extended power vacuum could further delay attempts to finalize a deal with the International Monetary Fund that would provide Lebanon with some three billion US dollarsin assistance, widely seen as a key step to help the country climb out of a three-year financial crisis that has left three quarters of the population in poverty.

While it is not the first time that Lebanon’s parliament has failed to appoint a successor by the end of the president’s term, this will be the first time that there will be both no president and a caretaker cabinet with limited powers.

Lebanon’s constitution allows the cabinet in regular circumstances to run the government, but is unclear whether that applies to a caretaker government.

Wissam Lahham, a constitutional law professor at St Joseph University in Beirut told The Associated Press that in his view, the governance issues the country will face are political rather than legal.

Although the constitution “doesn’t say explicitly that the caretaker government can act if there is no president, logically, constitutionally, one should accept that because… the state and institutions should continue to function according to the principle of the continuity of public services”, he said.

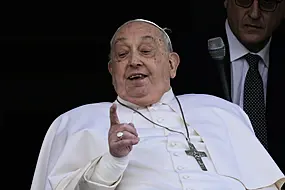

Lebanese are deeply divided over Mr Aoun, an 87-year-old Maronite Christian and former army commander, with some seeing him as a defender of the country’s Christian community and a leading figure who tried to seriously fight corruption in Lebanon.

His opponents criticise him for his role in the 1975-90 civil war and for his shifting alliances, especially with the Iran-backed Hezbollah, the country’s most powerful military and political force.

He has also come under fire for grooming his son-in-law to replace him, and many blame him for the economic crisis that is rooted in decades of corruption and mismanagement.

Mr Aoun, Lebanon’s 13th president since the country’s independence from France in 1943, saw Beirut’s historic relations with oil-rich gulf nations deteriorate because of Hezbollah’s powers and one of the world’s largest non-nuclear explosions at Beirut’s port in August 2020 that killed more than 200.