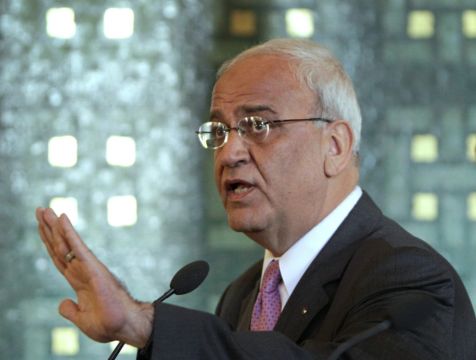

Saeb Erekat, a veteran peace negotiator and prominent international spokesman for the Palestinians for more than three decades, has died weeks after being infected by the coronavirus. He was 65.

The US-educated Mr Erekat was involved in nearly every round of peace negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians going back to the landmark Madrid conference in 1991, when he famously showed up draped in a black-and-white chequered keffiyeh, a symbol of Palestinian nationalism.

Over the next few decades, Mr Erekat was a constant presence in Western media, where he tirelessly advocated for a negotiated two-state solution to the decades-old conflict, defended the Palestinian leadership and blamed Israel for the failure to reach an agreement.

Mr Erekat’s Fatah party announced his death in a statement.

A relative and a Palestinian official later confirmed the news.

As a loyal aide to Palestinian leaders – first Yasser Arafat and then Mahmoud Abbas – Mr Erekat clung to this strategy until his death, even as hopes for Palestinian statehood sank to new lows.

Mr Abbas said Mr Erekat’s death was a “great loss for Palestine and our people, and we feel deeply saddened by his loss, especially in light of these difficult circumstances facing the Palestinian cause”.

Mr Erekat “will be remembered as the righteous son of Palestine, who stood at the forefront defending the causes of his homeland and its people”, Mr Abbas added, saying flags will be flown at half-mast for three days.

Yossi Beilin, a former Israeli cabinet minister and peace negotiator, called Mr Erekat’s death “a big loss for those who believe in peace, both on the Palestinian side and the Israeli side”.

Mr Erekat was born on April 28, 1955 in Jerusalem. He spent most of his life in the occupied West Bank town of Jericho, and as a child he witnessed Palestinians fleeing to nearby Jordan during the 1967 war in which Israel captured the West Bank, east Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip.

He studied abroad, earning a BA and MA in international relations from San Francisco State University and later moved to the UK, completing a PhD at the University of Bradford, where he focused on conflict resolution.

When he returned to the West Bank he became a professor at An-Najah University in Nablus and an editor at the Al-Quds newspaper. A self-described pragmatist, he invited Israeli students to visit the university in the late 1980s and condemned violence on all sides.

He was nevertheless convicted of incitement by an Israeli military court in 1987 after troops raided the university and found an English-language newsletter he had authored in which he wrote that “Palestinians must learn how to endure and reject and resist″ all the forms of occupation.

Mr Erekat insisted he was advocating peaceful resistance and not armed struggle, and he was later given an eight-month suspended sentence and fined £4,700.

The first Palestinian uprising erupted later that year in the form of mass protests, general strikes and clashes with Israeli troops. That uprising, along with US pressure on Israel, culminated in the Madrid conference, widely seen as the start of the Middle East peace process.

Mr Erekat was a prominent representative of Palestinians living inside the occupied territories at the time, but became a close aide to Mr Arafat when the exiled Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) returned to the territories following the 1993 Oslo accords.

In subsequent years he routinely served as Mr Arafat’s translator, and was sometimes accused of editing his remarks to soften the rough edges of the guerrilla leader-turned-aspiring statesman.

Throughout the 1990s, Mr Erekat was a frequent guest on news programmes, where he condemned violence on both sides but warned that the peace process was at risk of collapse because of Israel’s refusal to withdraw from the territories.

Mr Erekat was part of the Palestinian delegation at Camp David in 2000, when US president Bill Clinton brought the two sides together for marathon talks aimed at reaching a final agreement. The talks ended inconclusively and a few months later a second and far more violent uprising erupted.

Mr Arafat died in in 2004 but Mr Erekat continued as a top aide to Mr Abbas and served as a senior negotiator in sporadic peace efforts in the late 2000s.

Mr Erekat resigned as chief negotiator in 2011 after a trove of documents was leaked to the pan-Arab broadcaster Al-Jazeera showing that the Palestinian leadership had offered major concessions in past peace talks that were never made public.

But Mr Erekat remained a senior Palestinian official and a close adviser to Mr Abbas, who later appointed him secretary general of the PLO.

Israel and the Palestinians have not held substantive talks since Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu took office in 2009.

But Mr Erekat continued to call for a two-state solution based on the 1967 lines, accusing the Israeli leader of putting a “nail in the coffin” of hopes for peace by continuing to expand settlements.

Mr Erekat is survived by his wife, two sons, twin daughters and eight grandchildren.

He will be laid to rest in Jericho on Wednesday.