One of the Amazon river’s largest tributaries has reached its lowest level since official measurements began 121 years ago.

The level of the Rio Negro at the Brazilian city of Manaus confirms part of the world’s largest rainforest is suffering its worst drought, little more than two years after its most significant flooding.

Monday’s water level in the city’s port went as low as 13.5 metres, compared to the record level of 30.02 metres in June 2021.

The Rio Negro drains about 10% of the Amazon basin and is the world’s sixth largest by water volume.

The Madeira, another main tributary of the Amazon, has also recorded historically low levels which have halted the Santo Antonio hydroelectric dam, Brazil´s fourth largest.

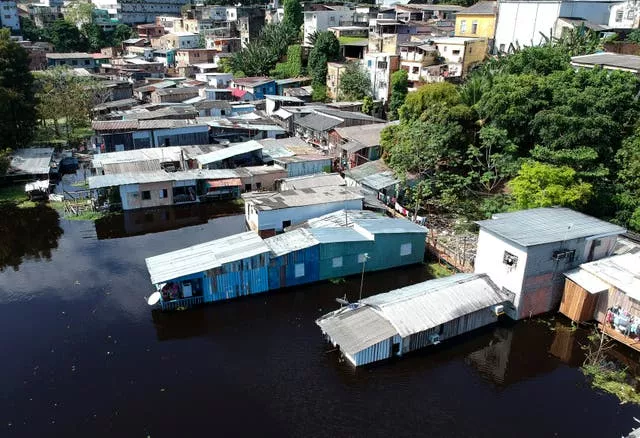

Low river levels throughout the Amazon have left hundreds of riverside communities isolated and struggling to get access to drinkable water, as well as disrupting commercial navigation which supplies Manaus.

With a population of two million, Manaus is the largest city and capital of Amazonas, the state hit hardest by the drought with 55 of 62 municipalities entering states of emergency due to the severe drought in September.

Manaus and other nearby cities are also suffering from high temperatures and heavy smoke from nearby man-caused fires for deforestation and pasture clearance while the drought is the likely cause of dozens of river dolphin deaths in Tefe Lake, near the Amazon River.

This is a startling contrast to July 2021, when the Rio Negro waters took over part of the Manaus downtown area, ruining crops of hundreds of riverine communities, for about three months.

Philip Fearnside, an American researcher at the Brazilian National Institute of Amazonian Research, said he expects the situation to deteriorate as surface water in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean is warmer than during the “Godzilla” El Nino of 2015-2016 and expanding.

In the Amazon, these Pacific warmings primarily lead to droughts in the northern part of the region.

A warm water patch in the tropical North Atlantic Ocean is causing drought in the southern part of the Amazon, similar to what happened in 2005 and 2010, according to researchers.

“The forecast is for the start of the rains to be delayed compared to normal, and for a drier-than-normal rainy season,” Mr Fearnside said.

“This could result not only in extreme low water this year, but also low levels in 2024.

“Until the rainy season begins in the basin, the situation that is already underway should worsen.”