In a statement carried by state broadcaster ORTM, the soldiers who staged Tuesday’s military coup identified themselves as the National Committee for the Salvation of the People, led by Colonel Major Ismael Wague.

“With you, standing as one, we can restore this country to its former greatness,” he said, announcing that borders were closed and that a curfew was going into effect from 9pm to 5am.

The news of Mr Keita’s departure was met with jubilation by anti-government demonstrators in the capital Bamako, and alarm by former colonial ruler France and other allies and foreign nations.

The UN Security Council scheduled a closed meeting for Wednesday afternoon to discuss the situation in Mali, where the UN has a 15,600-strong peacekeeping mission.

The West African regional bloc Ecowas said it was sending a high-level delegation to “ensure immediate return to constitutional order”.

Ecowas had previously sent mediators to try to negotiate a unity government but those talks fell apart when it became clear that the protesters would not accept less than Mr Keita’s resignation.

The bloc condemned the overthrow of Mr Keita, denied “any kind of legitimacy to the putschists”, and demanded sanctions against those who staged the coup and their partners and collaborators.

In its statement, Ecowas also said it would stop all economic, trade and financial flows and transactions between Ecowas states and Mali.

French President Emmanuel Macron condemned the coup, and spoke by telephone with Mr Keita and the leaders of Niger, Ivory Coast and Senegal as it was unfolding.

Mr Macron pledged full support to the Ecowas mediation effort, but his office said he would not comment further until after the UN Security Council meeting.

Mr Keita, who was democratically elected in a 2013 landslide and re-elected five years later, still had three years left in his term, but his popularity had plummeted, and demonstrators began taking to the streets calling for his removal in June.

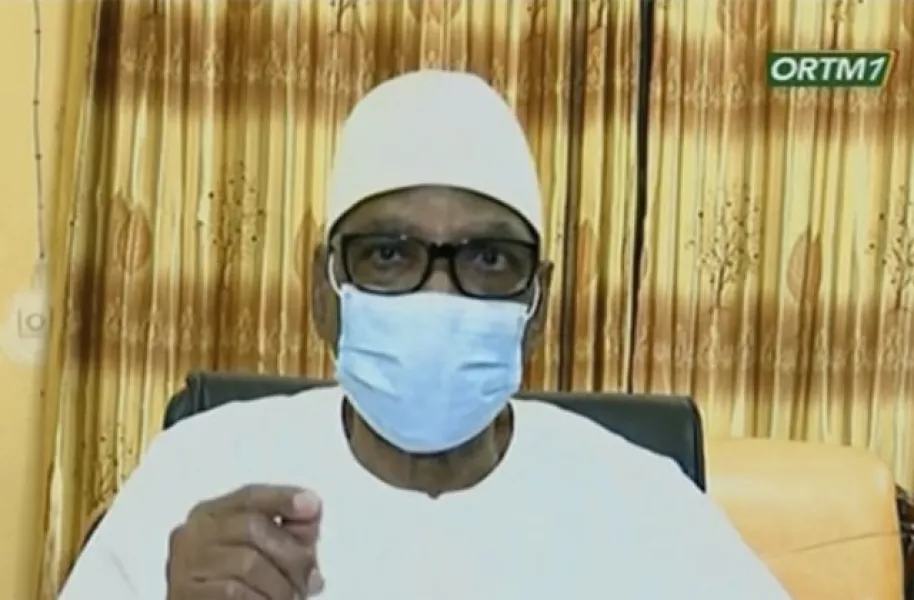

On Tuesday, soldiers forced his hand by surrounding his residence and firing shots into the air. Mr Keita and the prime minister were detained and hours later he appeared on state broadcaster ORTM. A banner across the bottom of the television screen referred to him as the “outgoing president”.

“I wish no blood to be shed to keep me in power,” he said. “I have decided to step down from office.”

He also announced that his government and the National Assembly would be dissolved, certain to further the country’s turmoil amid an eight-year Islamic insurgency and the growing coronavirus pandemic.

Mr Keita, who tried to meet protesters’ demands through a series of concessions, has enjoyed broad support from France and other Western allies. He was also believed to have widespread backing among high-ranking military officials, underscoring a divide between army leadership and unpredictable rank-and-file soldiers.

Tuesday marked a repeat of events leading up to the 2012 coup, which unleashed years of chaos in Mali when the ensuing power vacuum allowed Islamic extremists to seize control of northern towns. Ultimately a French-led military operation ousted the jihadists, but they regrouped and expanded their reach during Mr Keita’s presidency into central Mali.

His downfall closely mirrors that of his predecessor, Amadou Toumani Toure, who was forced out in 2012 after a series of punishing military defeats.

That time, the attacks were carried out by ethnic Tuareg separatist rebels. This time, Mali’s military has sometimes seemed powerless to stop extremists linked to al Qaida and so-called Islamic State.