Researchers found an acceleration in transmission between the Black Death of 1348 – estimated to have wiped out more than one-third of the population of Europe – and later epidemics, which culminated in the Great Plague of 1665.

They analysed thousands of documents covering a 300-year span of plague outbreaks in the city, and found that, in the 14th century, the number of people infected during an outbreak doubled approximately every 43 days.

By the 17th century, the number was doubling every 11 days, according to the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal.

It is an astounding difference in how fast plague epidemics grew

David Earn, a professor in the department of mathematics and statistics at McMaster University, Canada, and investigator with the Michael G DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research, led the study.

He said: “It is an astounding difference in how fast plague epidemics grew.”

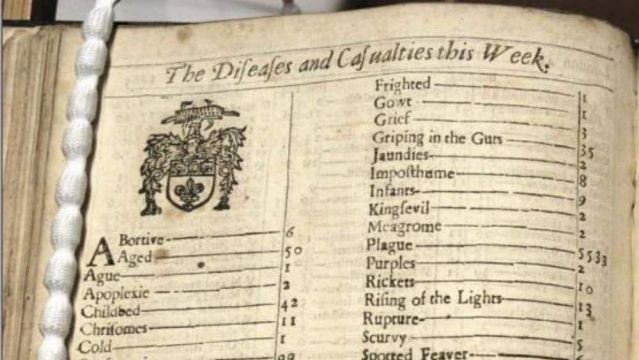

The researchers, including statisticians, biologists and evolutionary geneticists estimated death rates by analysing historical, demographic and epidemiological data from three sources – personal wills and testaments, parish registers, and the London Bills of Mortality.

Prof Earn said: “At that time, people typically wrote wills because they were dying or they feared they might die imminently, so we hypothesised that the dates of wills would be a good proxy for the spread of fear, and of death itself.

“For the 17th century, when both wills and mortality were recorded, we compared what we can infer from each source, and we found the same growth rates.

“No-one living in London in the 14th or 17th century could have imagined how these records might be used hundreds of years later to understand the spread of disease.”

Study co-author Hendrik Poinar, a professor in the department of anthropology at McMaster, said: “From genetic evidence, we have good reason to believe that the strains of bacterium responsible for plague changed very little over this time period, so this is a fascinating result.”

Researchers suggest the estimated speed of these epidemics, along with other information about the biology of plague, indicates that during these centuries the plague bacterium did not spread primarily through human-to-human contact, known as pneumonic transmission.

Growth rates for both the early and late epidemics are more consistent with bubonic plague, which is transmitted by the bites of infected fleas, the scientists suggest.

They believe population density, living conditions and cooler temperatures could potentially explain the acceleration, and that the transmission patterns of historical plague epidemics offer lessons for understanding Covid-19 and other modern pandemics.