The drama will unfold on Tuesday as the US has its first go at collecting asteroid samples for return to Earth, a feat accomplished only by Japan so far.

The Osiris-Rex mission is looking to bring back at least two ounces (60 grams) worth of asteroid Bennu, the biggest such haul from beyond the moon.

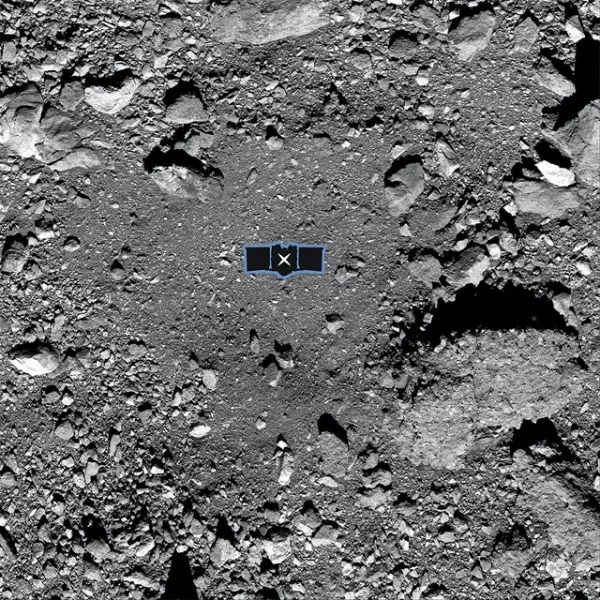

The van-sized spacecraft is aiming for the relatively flat middle of a tennis court-sized crater named Nightingale — a spot comparable to a few parking places here on Earth. Boulders as big as buildings loom over the targeted touchdown zone.

“So for some perspective, the next time you park your car in front of your house or in front of a coffee shop and walk inside, think about the challenge of navigating Osiris-Rex into one of these spots from 200 million miles away,” Nasa’s deputy project manager Mike Moreau said.

Once it drops out of its half-mile-high (0.75 km-high) orbit around Bennu, the spacecraft will take a deliberate four hours to make it all the way down, to just above the surface.

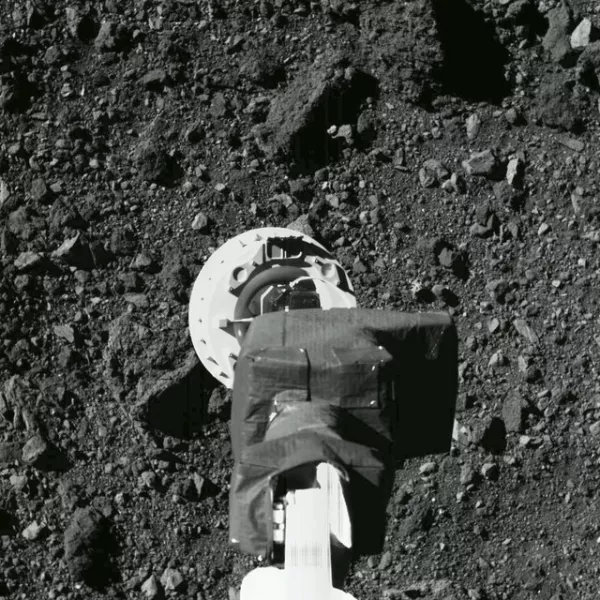

Then the action cranks up when Osiris-Rex’s 11-foot (3.4-metre) arm reaches out and touches Bennu.

Contact should last five to 10 seconds, just long enough to shoot out pressurised nitrogen gas and suck up the churned dirt and gravel.

Programmed in advance, the spacecraft will operate autonomously during the unprecedented touch-and-go manoeuvre. With an 18-minute lag in radio communication each way, ground controllers for spacecraft builder Lockheed Martin near Denver cannot intervene.

If the first attempt does not work, Osiris-Rex can try again. Any collected samples will not reach Earth until 2023.

While Nasa has brought back comet dust and solar wind particles, it has never attempted to sample one of the nearly one million known asteroids lurking in our solar system until now.

Japan, meanwhile, expects to get samples from asteroid Ryugu in December — in the milligrams at most — 10 years after bringing back specks from asteroid Itokawa.

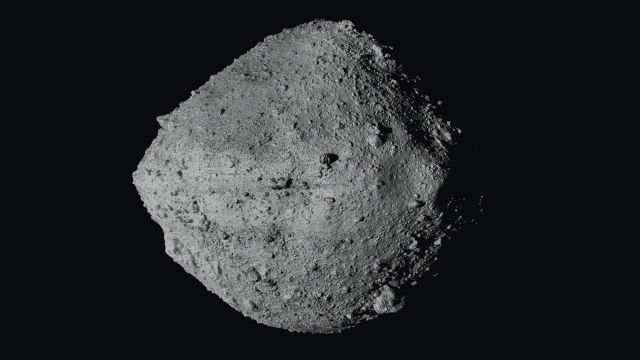

Bennu is an asteroid picker’s paradise. The big, black, roundish, carbon-rich space rock — taller than New York’s Empire State Building — was around when our solar system was forming 4.5 billion years ago.

Scientists consider it a time capsule full of pristine building blocks that could help explain how life formed on Earth and possibly elsewhere.

The mission’s principal scientist, Dante Lauretta of the University of Arizona, said: “This is all about understanding our origins.”