Inspired by the way brain cells usually connect, scientists created a synthetic “molecular bridge” called CPTX that allows novel interactions.

This was able to repair function in both cells and in mouse models of diseases and injury, the team behind the development said.

According to the research published in Science, the design could be extended to connect other cell types or could be used to remove problematic connections in disorders such as epilepsy.

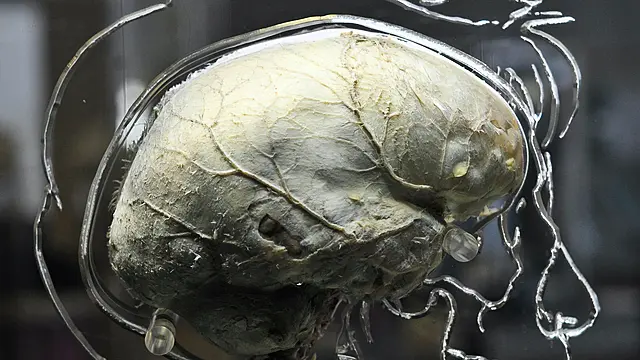

Cerebellin-1 is a molecule that connects neuronal cells – that send signals – with receiver cells at special points of contact called synapses.

We created a molecule that we believed would help repair or replace neuronal connections in a simple and efficient way

Cerebellin-1 and its related proteins, known as “synaptic organisers”, are essential to help establish the communication network that underlies all nervous system functions.

Researchers wanted to see if they could cut and paste structural elements from different organiser molecules to generate new ones with different binding properties.

The study involved scientists from the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology (MRC LMB) at Cambridge, and collaborators from Japan and Germany.

Radu Aricescu, of the MRC LMB, said: “Damage in the brain or spinal cord often involves loss of neuronal connections in the first instance, which eventually leads to the death of neuronal cells.

“Prior to neuronal death, there is a window of opportunity when this process could be reversed in principle.

“We created a molecule that we believed would help repair or replace neuronal connections in a simple and efficient way.

“We were very much encouraged by how well it worked in cells and we started to look at mouse models of disease or injury where we see a loss of synapses and neuronal degeneration.”

Researchers said the results were striking in all the animal models, with restored neuronal connections and improvements in memory, co-ordination and movement tests.

They saw the greatest impact in spinal cord injury where motor function was restored for at least seven to eight weeks following a single injection into the site of injury.

In the brain, the positive impact of injections was observed for a shorter time, down to only about one week.

The scientists are now developing new and more stable versions of CPTX, but cautioned that a lot more work is needed to find out if the findings in mice are applicable in humans.