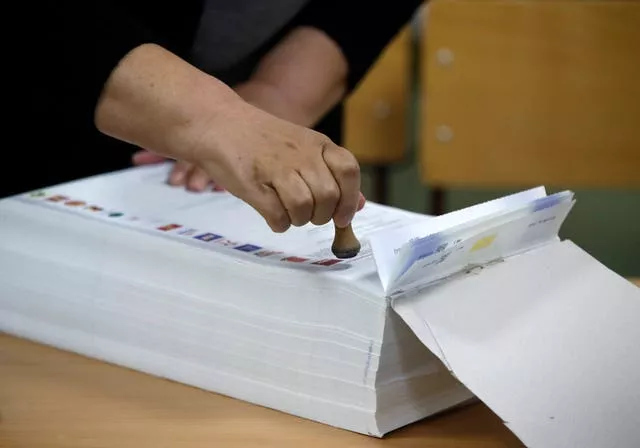

Voters in North Macedonia are casting ballots in a parliamentary election and presidential runoff dominated by issues including the country’s path toward European Union membership, corruption and the economy.

The first round of the election for president, a largely ceremonial post, was seen as a barometer for the parliamentary vote.

It gave a clear lead to Gordana Siljanovska-Davkova, the candidate backed by the centre-right opposition, over incumbent Stevo Pendarovski, who is supported by the governing centre-left coalition.

Ms Siljanovska-Davkova garnered 41.2 per cent, in the first round on April 24th, compared to 20.5 per cent for Mr Pendarovski.

The two had also squared off in the previous election in 2019, when Mr Pendarovski won with nearly 54 per cent of the vote.

Turnout in the runoff must be at least 40 per cent for the result to be valid.

In the parliamentary election, more than 1,700 candidates are vying for the 120 seats in the unicameral assembly.

There are also three seats reserved for expatriates, but in the previous election in 2020, turnout was too low for them to be filled.

The month-long campaign focused on North Macedonia’s progress toward joining the 27-nation EU, the rule of law, corruption, fighting poverty and tackling the country’s sluggish economy.

Skopje voter Atanas Lovacev expressed disappointment with the current government, but had low expectations from whoever comes next.

“Yes, (I expect changes), because the current government did nothing,” he said.

“But I don’t expect anything either from the new government. They all make promises, but the result is nothing.”

Opinion polls ahead of the vote had consistently shown the centre-right opposition VMRO-DPMNE party, at the head of a 22-party coalition called “Your Macedonia,” with a double-digit lead over the coalition “For A European Future,” led by the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia, or SDSM.

There are also two coalitions representing ethnic Albanians, who account for a quarter of North Macedonia’s population.

They include the European Front, led by the Democratic Union of Integration (DUI), which has been the coalition partner of all governments of the past 20 years.

But VMRO-DPMNE leader Hristijan Mickoski wants to ally with the VLEN (Worth) four-party coalition, which has positioned itself to the right of DUI.

North Macedonia’s path to the EU is being blocked by neighbouring Bulgaria, which demands that the constitution be amended to recognise a Bulgarian minority.

And while the centre-left has agreed to the demand, VMRO-DPMNE has denounced the government’s “capitulation (to) Bulgarian dictates”.

Just over 3,500 people out of nearly 1.84 million identified themselves as Bulgarians in North Macedonia’s latest census, in 2021.

North Macedonia has been a candidate to join the EU since 2005, but was blocked for years by neighbouring Greece in a dispute over the country’s name.

That was resolved in 2018, but Bulgaria is now the one blocking the process — it has said it will only lift its veto once the constitution is amended.

Skopje resident Gordana Gerasimovski said she was disappointed that the country had been waiting for so long to join the EU, but hoped there would now be real progress.

“We should have been part of European Union long time ago. This is what we are lacking, but we hope that the time will get us where we want to be for so long,” she said.

EU membership negotiations with North Macedonia — and fellow-candidate Albania — began in 2022 and the process is expected to take years.

Corruption is the other hot-button issue, with a European Commission report last year saying it “remains prevalent in many areas” of North Macedonia.