To admirers, the three-time Italian premier Silvio Berlusconi was a charismatic statesman who sought to elevate Italy on the world stage.

To his critics, he was a populist who threatened to undermine democracy, wielding political power as a tool to enrich himself and his businesses.

When former US president Donald Trump launched his political career, many drew comparisons to Mr Berlusconi, noting they both had long business careers before entering politics, sought to upend the existing order, and grabbed attention for their over-the-top personalities and lavish lifestyles.

Silvio Berlusconi was born in Milan on September 29 1936, the son of a banker.

He earned a law degree and sang in nightclubs and on cruise ships, before starting a construction company and building apartments for middle-class families.

Mr Berlusconi’s astronomical wealth came from media holdings. In the 1970s and 1980s, he circumvented Italy’s state TV monopoly RAI by creating his own network of local stations.

RAI and Mediaset accounted for about 90% of the national market in 2006.

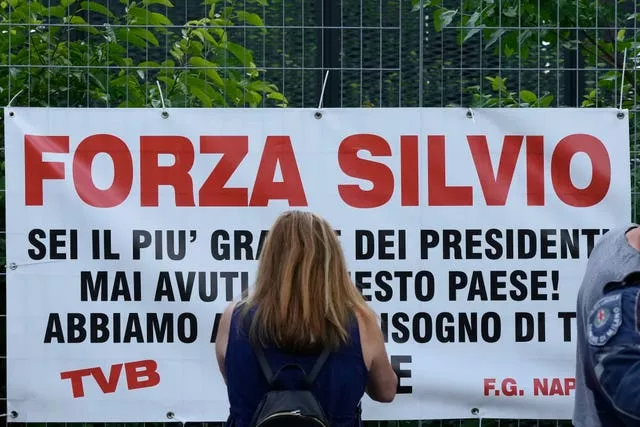

When corruption scandals of the 1990s decimated the political establishment, Mr Berlusconi founded Forza Italia in 1994 – its name comes from the football chant: “Let’s go, Italy.”

His first government collapsed after eight months when an ally who led an anti-immigrant party pulled its support. But, aided by an aggressive campaign, Mr Berlusconi swept to victory again in 2001 and was in power for five years, setting a record for government longevity in Italy.

As a businessman who knew the power of images, Mr Berlusconi introduced US-style campaigns that broke with the grey world of Italian politics. His rivals struggled to adapt.

A Group of Eight summit he hosted in Genoa in 2001 was marred by violent demonstrations. He constantly faced accusations of sponsoring laws aimed at protecting himself or his businesses, but insisted he always acted in the interest of all Italians.

An admirer of US president Ronald Reagan and prime minister Margaret Thatcher, Mr Berlusconi passed reforms that partially liberalised the labour and pension systems, which were among Europe’s most inflexible.

Mr Berlusconi saw himself as Italy’s saviour from what he described as the Communist menace, years after the Berlin Wall fell. He portrayed himself as the target of a judiciary he said was filled with leftist sympathisers.

His friendship with Socialist leader and former premier Bettino Craxi was widely credited for helping him become a media baron.

Still, Mr Berlusconi billed himself as a self-made man.

His second term in office, from 2001-06, was perhaps his golden era, when he became Italy’s longest-serving head of government and boosted its global profile through his friendship with then-US president George W Bush.

Bucking opposition at home and in Europe, Mr Berlusconi backed the US-led war in Iraq and sent 3,000 troops.

He flouted political etiquette and stirred anger with some of his comments, such as claiming after the September 11 terror attacks in 2001 that Western civilisation was superior to Islam.

But in 2006, as Italy was ridiculed as “the sick man of Europe”, with its economy mired in zero growth and its budget deficit rising, Mr Berlusconi narrowly lost the general election to centre-left leader Romano Prodi.

He won his final term as premier in 2008, reluctantly stepping down in 2011 when financial markets lost faith in his ability to keep Italy from succumbing to the eurozone’s sovereign debt crisis.

His party was eclipsed as the dominant force on Italy’s right – first by the League, led by anti-migrant populist Matteo Salvini, then by Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party, with its roots in neo-fascism.

Following 2022 elections, Ms Meloni formed a governing coalition with the help of Forza Italia.

Mr Berlusconi eventually lost his standing as Italy’s richest man, although his media and luxury real estate holdings still left him a billionaire several times over.

He was dogged by a number of scandals concerning his sex-fuelled “bunga bunga” parties and allegations of corruption.

Criminal cases ended in dismissals when statutes of limitations ran out in Italy’s slow-moving justice system, or with Mr Berlusconi being victorious on appeal.

Investigations targeted the tycoon’s so-called “bunga bunga” parties involving young women and minors, or his businesses, which included the football team AC Milan, the country’s three biggest private TV networks, magazines, a daily newspaper, and advertising and film companies.

Only one of these inquiries led to a conviction – a tax fraud case stemming from a sale of movie rights in his business empire.

The conviction was upheld in 2013 by Italy’s top criminal court, but he was spared prison because of his age – then 76 – and was ordered to do community service by assisting Alzheimer’s patients.

He still was stripped of his senate seat and banned from running or holding public office for six years, under anti-corruption laws.

PM Netanyahu:

"I was deeply saddened by the passing of Silvio Berlusconi, the former Prime Minister of Italy. My heartfelt condolences go out to his family and to the people of Italy.

Silvio was a great friend of Israel and stood by us at all times. Rest in peace my friend."— Prime Minister of Israel (@IsraeliPM) June 12, 2023

In 2013, guests at one of Mr Berlusconi’s parties included an under-age Moroccan dancer whom prosecutors alleged had sex with Mr Berlusconi in exchange for cash and jewellery.

After a trial, a Milan court initially convicted Mr Berlusconi of paying for sex with a minor and using his office to try to cover it up. Both denied having sex with each other, and he was eventually acquitted.

The Catholic Church was scandalised by his antics, and his wife of nearly 20 years divorced him – but Mr Berlusconi was unapologetic, declaring: “I’m no saint.”

The former Italian leader also had close ties with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

On his 86th birthday, while the war in Ukraine raged, Mr Putin sent Mr Berlusconi best wishes and vodka, while the Italian boasted he returned the favour by sending back Italian wine.

He was dogged by health concerns, having undergone surgery for prostate cancer in 1997.

In November 2006, he fainted during a speech, and the next month flew to the US, where he received a pacemaker at the Cleveland Clinic. He underwent more heart surgery in 2016.

Mr Berlusconi was first married in 1965 to Carla Dall’Oglio, and their two children, Marina and Piersilvio, were groomed to hold top positions in his business empire.

He then married Veronica Lario in 1990, and they had three children: Barbara, Eleonora and Luigi.