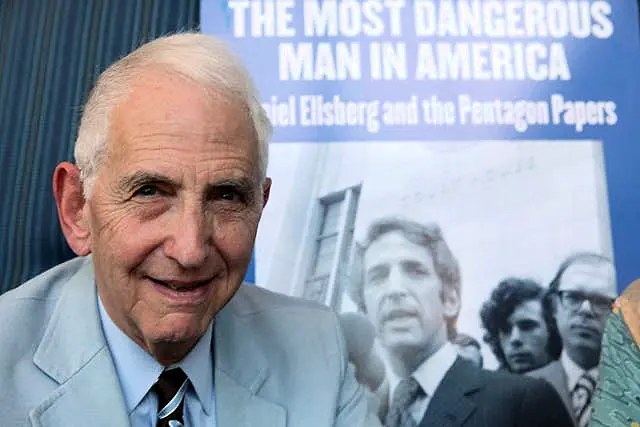

Daniel Ellsberg, the whistleblower who leaked the Pentagon Papers revealing government doubts and deceit about the Vietnam War, has died aged 92.

Mr Ellsberg, who announced in February that he was terminally ill with pancreatic cancer, died on Friday morning, according to a letter from his family released by a spokeswoman, Julia Pacetti.

Until the early 1970s, when he revealed that he was the source for the stunning media reports on the 7,000-page Defence Department study of the US role in Indochina, Mr Ellsberg was a well-placed member of the government-military elite.

He was a Harvard graduate and self-defined “cold warrior” who served as a private and government consultant on Vietnam throughout the 1960s, risked his life on the battlefield, received the highest security clearances and came to be trusted by officials in Democratic and Republican administrations.

He was especially valued, he would later note, for his “talent for discretion”.

But like millions of other Americans, in and out of government, he had turned against the years-long war in Vietnam, the government’s claims that the battle was winnable and that a victory for the North Vietnamese over the US-backed South would lead to the spread of communism throughout the region.

Unlike so many other war opponents, he was in a special position to make a difference.

“An entire generation of Vietnam-era insiders had become just as disillusioned as I with a war they saw as hopeless and interminable,” he wrote in his 2002 memoir, Secrets: A Memoir Of Vietnam And The Pentagon Papers.

“By 1968, if not earlier, they all wanted, as I did, to see us out of this war.”

The Pentagon Papers had been commissioned in 1967 by then-defence secretary Robert S McNamara, a leading public advocate of the war who wanted to leave behind a comprehensive history of the US and Vietnam and to help his successors avoid the kinds of mistakes he would only admit to long after.

The papers covered more than 20 years, from France’s failed efforts at colonisation in the 1940s and 1950s to the growing involvement of the US, including the bombing raids and deployment of hundreds of thousands of ground troops during Lyndon Johnson’s administration.

Mr Ellsberg was among those asked to work on the study, focusing on 1961, when the newly-elected president John F Kennedy began adding advisers and support units.

First published in The New York Times in June 1971, with The Washington Post, The Associated Press and more than a dozen others following, the classified papers documented that the US had defied a 1954 settlement barring a foreign military presence in Vietnam, questioned whether South Vietnam had a viable government, secretly expanded the war to neighbouring countries and had plotted to send American soldiers even as Mr Johnson vowed he would not.

The Johnson administration had dramatically and covertly escalated the war despite the “judgment of the Government’s intelligence community that the measures would not” weaken the North Vietnamese, wrote the Times’ Neil Sheehan, a former Vietnam correspondent who later wrote a Pulitzer Prize winning book on the war, A Bright Shining Lie.

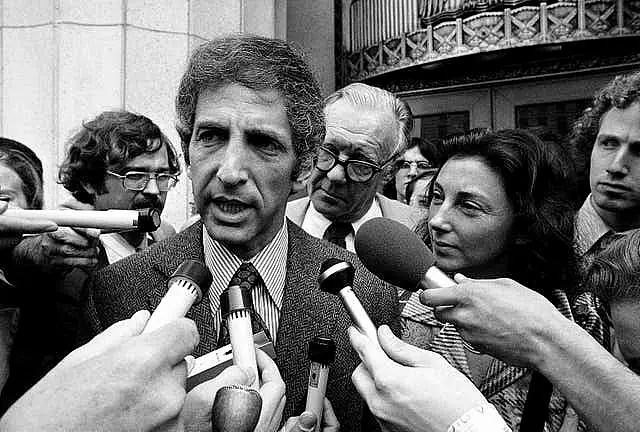

The leaker’s identity became a national guessing game and Mr Ellsberg proved an obvious suspect, because of his access to the papers and his public condemnation of the war over the previous two years.

With the FBI in pursuit, Mr Ellsberg turned himself in to authorities in Boston, became a hero to the anti-war movement and a traitor to the war’s supporters, labelled the “most dangerous man in America” by national security adviser Henry Kissinger, with whom Ellsberg had once been friendly.

Mr Ellsberg faced trials in Boston and Los Angeles on federal charges for espionage and theft, with a possible sentence of more than 100 years.

But the Boston case ended in a mistrial because the government wiretapped conversations between a defence witness and his attorney. Charges in the Los Angeles trial were dismissed after Judge Matthew Byrne learned that White House “plumbers” G Gordon Liddy and E Howard Hunt had burgled the office of Mr Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in Beverly Hills, California.

Mr Ellsberg is survived by his second wife, the journalist Patricia Marx, and three children, two from his first marriage.