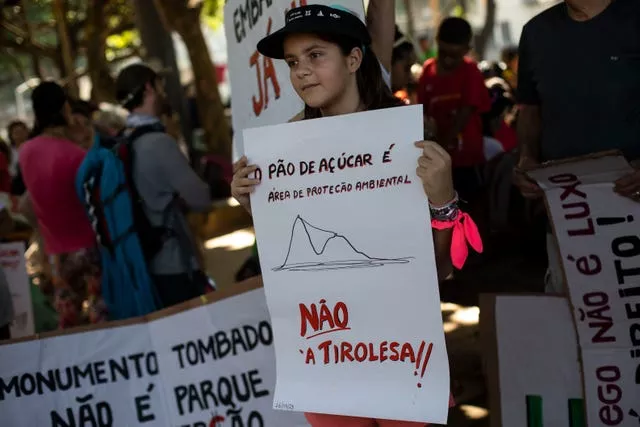

Around 200 protesters gathered beneath Rio de Janeiro’s world-famous Sugarloaf Mountain to protest against the ongoing construction of ziplines aimed at boosting tourism, alleging it will have an unacceptable impact.

The four steel lines will run 755 metres over the forest between Sugarloaf and Urca Hill, with riders reaching speeds of 62mph.

Inauguration is scheduled for the second half of this year, and an online petition to halt work has been signed by almost 11,000 people.

Sugarloaf – known in Portuguese as Pao de Acucar – juts out of the earth at the entrance to Rio’s bay.

The United Nations heritage body Unesco named it a World Heritage Site in 2012 along with Rio’s other marquee mountains. Years beforehand, Brazil’s heritage institute designated it a national monument.

The cable cars to its summit draw hundreds of thousands of Brazilian and international tourists each year, all eager to take in the panoramic views of the sprawling city’s beaches and forested mountains.

It is also a popular spot for sport climbing and birdwatching with preserved Atlantic Forest in a conservation unit, which towers over the sleepy Urca neighbourhood.

As such, the prospect of riders buzzing down wires while screaming wildly has united mountaineers, environmental activists and residents in opposition.

They warn that Unesco could withdraw its heritage status. One protester on Sunday held a sign reading: “S.O.S. UNESCO”, and the group often broke out into chants of: “Zipline out!”

Andre Ilha, a former director of biodiversity and protected areas of Rio state’s environment institute and founder of environmental non-profit Ecological Action Group, said: “We are completely opposed to the transformation – which in truth has been happening for some time – of the summits of Urca Hill and Sugarloaf into an entertainment hub.

“This is inducing people to go there for reasons that aren’t why the cable car was conceived: To appreciate the landscape,” he said.

Many residents of Urca are similarly upset.

Aurimar dos Prazeres, president of a residents’ association, said: “We live in a small, peaceful neighbourhood. There will be visual and audible impact; no one goes down a zipline in silence.

“And it isn’t one zipline. It’s four of them. One hundred people going down each hour. That’s craziness, and (will have a) very big impact.”

Parque Bondinho Pao de Acucar, which operates the cable cars and is behind the 50-million reais project, said in a statement that sound tests indicate noise from riders will not be perceptible from below, nor will it affect climbing routes.

It says it has obtained all the necessary authorisations and licenses for the project from the national heritage institute and municipal authorities, and it touts the ability to drive tourism.

“In addition to the great integration with nature, the intention is to improve the experience of our visitors and make the visit to the Parque Bondinho Pao de Acucar Park even more pleasant and unforgettable,” the company says on the zipline’s website.

The company also says it consulted the community ahead of time. Residents, at least, say that is not true.

Ms Prazeres told The Associated Press her association was not approached until after work was already under way, and followed complaints.

Juliana Freire, president of another residents association, told the AP the company brought up its intention to develop the zipline during a 2022 meeting about another subject, but never made any formal presentation.

Activists on Sunday also expressed concern the zipline is a harbinger of future interventions. The company that administers the cable cars is studying a project that would modify the structure at Sugarloaf’s summit.

Opponents have nicknamed it “the castle of horrors” and warn that it could augur all sorts of potential constructions – almost none of which appear in the company’s proposal.

The company says the future project would not entail expansion of its current footprint nor the opening of new stores, and is meant to facilitate observation of the landscape, improve accessibility for disabled people and separate the flow of tourists, workers and cargo.