Russian authorities are seeking a 13-year prison sentence for opposition leader Alexei Navalny in a trial Kremlin critics see as an attempt to keep President Vladimir Putin’s most ardent foe in prison for as long as possible.

Navalny, who is already serving two and a half years in a penal colony east of Moscow, has been charged with fraud and contempt of court.

The prosecution accuses him of embezzling money that he and his foundation raised over the years and of insulting a judge during a previous trial.

Navalny has rejected the allegations as politically motivated.

In their closing arguments on Tuesday, the prosecution asked for 13 years in a maximum security prison for the anti-corruption crusader and a 1.2 million-rouble (roughly £8,200) fine.

It is not immediately clear if Navalny is expected to serve this sentence concurrently with his current punishment, or on top of it.

Navalny’s top ally, Leonid Volkov, who has left Russia where he is facing multiple criminal cases himself, claimed in a Facebook post that the authorities want the politician to remain in prison “until the end of the life of one of the two people – Navalny himself or Vladimir Putin”.

After the prosecution’s closing arguments, the judge announced a brief recess before hearing the defence’s statements.

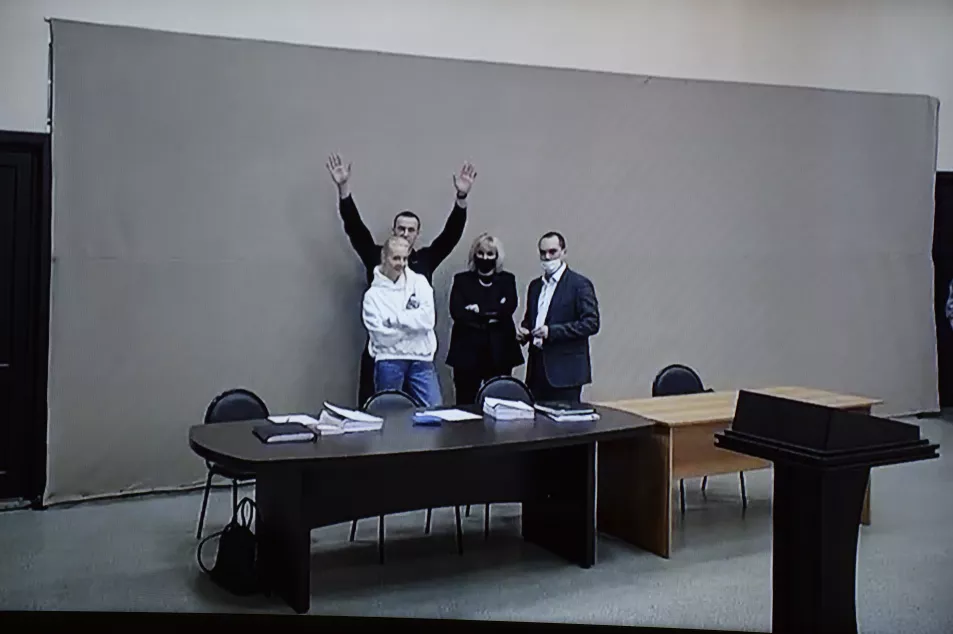

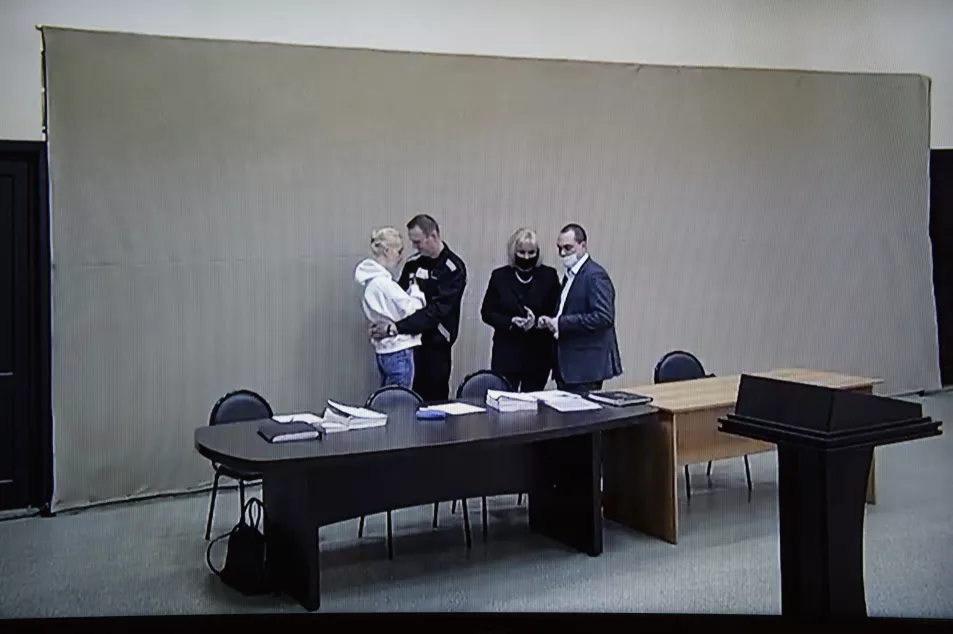

The trial, which opened exactly a month ago, unfolded in a makeshift courtroom in the prison colony hours away from Moscow where Navalny is serving a sentence for parole violations.

Navalny’s supporters have criticised the authorities’ decision to move the proceedings there from a courthouse in Moscow, saying it has effectively limited access to the proceedings for the media and supporters.

Navalny, 45, has appeared at hearings wearing prison garb and made several elaborate speeches during the trial, decrying the charges against him as bogus.

He was arrested in January 2021 immediately upon his return from Germany, where he spent five months convalescing from a poisoning he blamed on the Kremlin, a claim Russian officials vehemently denied.

Shortly after the arrest, a court sentenced him to two and a half years in jail over the parole violations stemming from a 2014 suspended sentence in a fraud case that Navalny insists was politically driven.

Following Navalny’s imprisonment, authorities unleashed a sweeping crackdown on his associates and supporters.

His closest allies have left Russia after facing multiple criminal charges, and his Foundation for Fighting Corruption and a network of nearly 40 regional offices were outlawed as extremist – a designation that exposes people involved to prosecution.

Last month, Russian officials added Navalny and a number of his associates to a state registry of extremists and terrorists.

Several criminal cases have been launched against Navalny individually, leading his associates to suggest the Kremlin intends to keep him behind bars for as long as possible.

Members of Navalny’s defence team have complained they were not allowed to bring mobile phones or laptops containing case files into the courtroom at the penal colony.