Now he sleeps at a prison, although there is a social media campaign for him to be returned to his old stomping ground.

Kataza is a baboon, one of a few hundred urban primates who live around Cape Town and are often a nuisance when they invade properties looking for food.

They knock over bins, steal fruit and vegetables from gardens, and generally cause trouble.

Kataza’s story is the latest in Cape Town’s ongoing dilemma over how to deal with the baboons, who live in the craggy mountains that surround the city but often jump at the chance to roam through residential areas and scavenge for anything edible.

There are around 15 troops in the greater Cape Town area and something in the region of 500 baboons, according to experts.

The city even has a Baboon Technical Team – wildlife rangers chase baboons away from some neighbourhoods by shooting paintball guns at them.

The most persistently troublesome primates are sometimes euthanised.

Kataza operated in the seaside village of Kommetjie, on Cape Town’s southern peninsula.

After he was captured, rangers relocated him to the nearby area of Tokai, hoping he would integrate with another, better-behaved troop and stop his mischief.

Activists, however, want him to be taken home and reunited with his own troop.

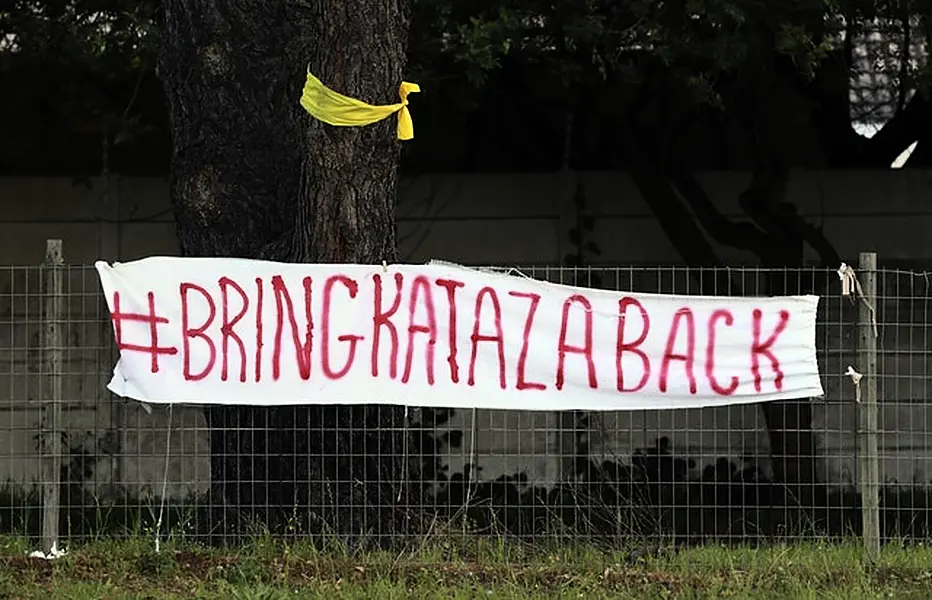

“#BringBackKataza” reads a sign posted by a road in Kommetjie.

There is also a Facebook page calling for his safe return.

Jenni Trethowan, who runs Baboon Matters – a conservation organisation in Cape Town that seeks ways for humans and baboons to peacefully co-exist – said Kataza has been unfairly singled out.

She wants him back in Kommetjie.

“He’s no worse than any of the other baboons – he’s just an urban baboon,” Ms Trethowan said.

Ms Trethowan has spent many days observing Kataza since he was relocated late last month.

He has not integrated with the Tokai troop, she said, is isolated and appears to be depressed.

Kataza now spends his days wandering through the streets of Tokai and his nights sleeping in the yard of a local prison.

“He lowers himself over the prison wall or just ambles through the gate,” she said.

Authorities keep what they call “rap sheets” that list a baboon’s misdemeanours – and Kataza’s was apparently extensive.

They had watched him since April, when he raided five occupied houses.

The final straw came when he led his troop on 15 raids through Kommetjie in July and August, they said.

“He generally solicited other individuals to join him in raiding town,” Kataza’s rap sheet says, according to a South African newspaper that viewed the document.

Ms Trethowan said the city is just blaming baboons for being baboons.

Instead, Cape Town should take measures to ease the problem and baboon-proof bins would help, she said.

“Baboons are criminalised for things that baboons do normally,” Ms Trethowan said.

“They are just opportunistic foragers.”