Sri Lanka has lifted a six-week lockdown as Covid-19 cases and deaths decline.

Despite the end of the lockdown and a curfew, strict restrictions remain. People are only allowed out for work or to buy essentials. Public gatherings are banned while cinemas, schools and restaurants will still be closed, according to the health ministry. Strict rules are also imposed on public transport, weddings and funerals.

The government has increased vaccination in recent months, with more than 50% of the 22 million people now fully inoculated.

New daily infections have since fallen to below 1,000 and deaths to under 100, from a peak of more than 3,000 cases and more than 200 deaths early September. The country has reported more than 516,000 infections and 12,847 deaths.

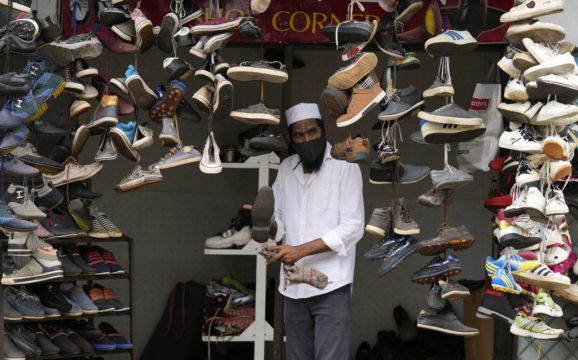

The lifting of the lockdown is hoped to boost tourism and ease a decline in foreign exchange that had led to a shortage of essential items such as milk powder, sugar and cooking gas. Long lines formed outside shops in the capital Colombo and its suburbs as people rushed to buy milk powder.

“I am really fed up with these shortages, firstly gas, then rice and now milk powder,” Chandana Kumara, 46, a labourer at a private company, said while waiting in a queue to buy milk powder.

“I don’t know to whom should I blame… but these things have made my life miserable, and my only worry is that this condition would continue for quite some time,” he said.

Officials and traders said more than 800 containers carrying essentials were stuck in the country’s main port due to the lack of US dollars to pay for them.

State Minister of Consumer Protection Lasantha Alagiyawanna said the government was taking steps to resolve the problem to clear cargoes of essential items including lentils and milk powder.

Sri Lanka’s government has curtailed foreign currency outflows after the island nation’s economy contracted by 3.6% last year, its deepest recession since independence from Britain 73 years ago. The government has also cut back on imports of cars, farm chemicals and hundreds of other foreign-made goods.

The move to save foreign exchange is apparently to ensure the country can meet foreign debt repayment and rising debt obligation. The Sri Lankan rupee has been gradually weakening against other major currencies, making such repayments more costly in local terms.

“Yes, the country has been facing a foreign currency crisis,” said government spokesman Ramesh Pathirana.

He pinned the blame on a loss in income of about £5 billion from the tourism sector over the last two years. Tourism accounts for about 5% of Sri Lanka’s GDP and is the country’s second largest foreign exchange earner. The sector employs more than three million people.