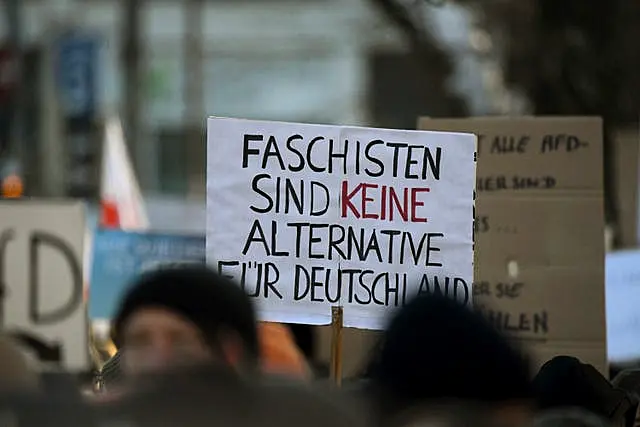

Tens of thousands of people have protested against the far right in cities across Germany, attending events with slogans such as “Never Again is Now”, “Against Hate” and “Defend Democracy”.

The large crowds were the latest in a series of demonstrations that have been gaining momentum in recent days.

They came in the wake of a report that right-wing extremists recently met to discuss the deportation of millions of immigrants, including some with German citizenship.

Some members of the far-right Alternative for Germany party, or AfD, were present at the meeting.

Police said a Saturday afternoon protest in Frankfurt drew 35,000 people. Demonstrations in Stuttgart, Nuremberg and Hannover also drew large crowds.

A similar demonstration on Friday in Hamburg, Germany’s second-largest city, drew what police said was a crowd of 50,000 and had to be ended early because the mass of people led to safety concerns.

Additional protests planned for Sunday in other major German cities, including Berlin, Munich and Cologne, are also expected to draw tens of thousands of people.

Although Germany has seen other protests against the far right in past years, the size and scope of protests being held this weekend — not just in major cities but also in dozens of smaller cities across the country — are notable.

Saturday’s crowds were a sign that the protests seem to be galvanising popular opposition to the AfD in a new way.

What started out as relatively small gatherings have grown into protests that, in many cases, are drawing far more participants than organisers expected.

The catalyst for the protests was a report from the media outlet Correctiv last week on an alleged far-right meeting in November, which it said was attended by figures from the extremist Identitarian Movement and from the AfD.

A prominent member of the Identitarian Movement, Austrian citizen Martin Sellner, presented his “remigration” vision for deportations, the report said.

The AfD has sought to distance itself from the extremist meeting, saying it had no organisational or financial links to the event, that it was not responsible for what was discussed there and members who attended did so in a purely personal capacity.

Still, one of the AfD’s co-leaders, Alice Weidel, has parted ways with an adviser who was there while also criticising the reporting itself.

The protests also build on growing anxiety over the last year about the AfD’s rising support among the German electorate.

The AfD was founded as a Eurosceptic party in 2013 and first entered the German Bundestag in 2017.

Polling now puts it in second place nationally with around 23%, far above the 10.3% it won during the last federal election in 2021.

Last summer, candidates from the AfD won the party’s first mayoral election and district council election, the first far-right party to do so since the Nazi era, and in state elections in Bavaria and Hesse the party made significant gains.

The party leads in several states in eastern Germany, the region where its support is strongest including three – Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia – that are due to hold elections this autumn.

As a result, Germany is grappling with how best to respond to the party’s popularity.

The widespread anger over the Correctiv report has prompted renewed calls for Germany to consider seeking a ban on the AfD.

On Saturday, the Brandenburg chapter of Germany’s Greens voted at a party convention in favour of pursuing a potential ban to help prevent the rise of “a new fascist government in Germany”.

However, many of the AfD’s opponents have spoken out against the idea, arguing that the process would be lengthy, success is highly uncertain and it could benefit the party by allowing it to portray itself as a victim.

Elected officials from across the political spectrum, including Chancellor Olaf Scholz, expressed their support for the protests.

“From Cologne to Dresden, from Tuebingen to Kiel, hundreds of thousands are taking to the streets in Germany in the coming days,” Mr Scholz said in his weekly video statement, adding that protesters’ efforts are an important symbol “for our democracy and against right-wing extremism”.

Friedrich Merz, head of the centre-right Christian Democrats, said the protests show Germans are “against every form of hate, against incitement and against forgetting history”.