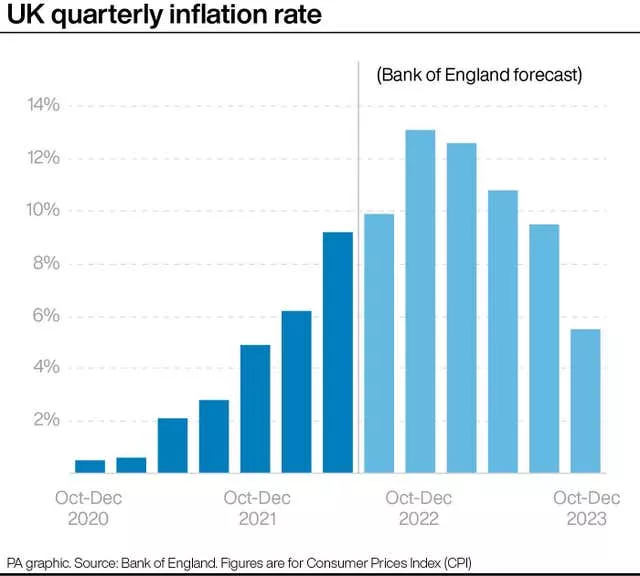

Britons face two years of tumbling household incomes with inflation set to soar to more than 13 per cent and the economy plunging into the longest recession since the financial crisis, the Bank of England has warned.

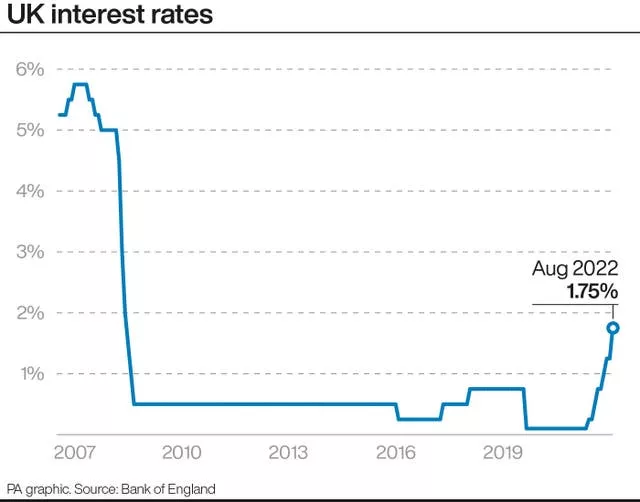

The UK Bank made the grim prediction as it raised interest rates from 1.25 per cent to 1.75 per cent, the biggest increase for 27 years. The move, aimed at controlling runaway inflation, puts further pressure on mortgage holders.

In a dire outlook for UK economy, the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) forecast inflation peaking at 13.3 per cent in October, the highest for more than 42 years.

The runaway costs are largely due to the soaring price of energy, as the fallout from Russian president Vladimir Putin’s war against Ukraine forced gas prices skywards.

Regulator Ofgem is expected to push up the cap on household energy bills to around £3,450 in October, the Bank said.

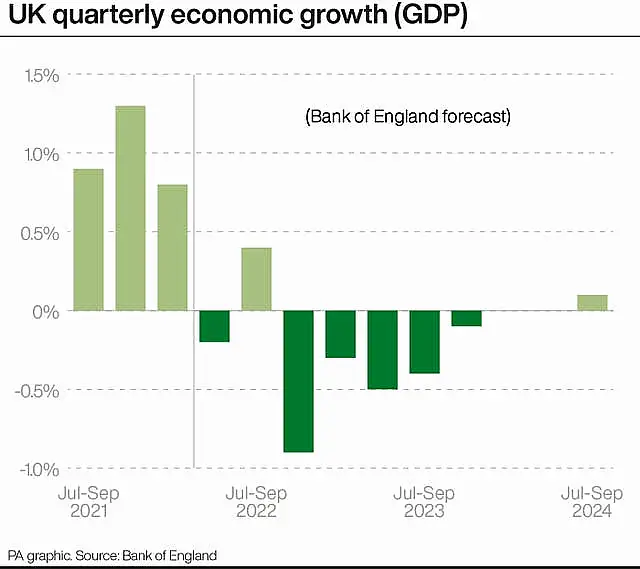

The energy price will help kick off a five-quarter recession as the Bank forecast gross domestic product (GDP) to shrink in every three-month period from October to the start of 2024. GDP will fall by as much as 2.1 per cent, the Bank said.

The report paints a stark picture for households. On a real basis their post-tax incomes are set to fall 1.5 per cent this year and 2.25 per cent next, despite the current Government support.

It would be the first time since records began in the 1960s that household incomes have fallen for two years in a row.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation chief economist Rebecca McDonald said: “We already know seven million low-income families had to sacrifice food, heating, even showers, this year because they couldn’t afford them.

“While the Government might have taken a break from acting on the cost-of-living emergency, these families can’t take a holiday from the year of financial fear.

“They will be wondering why further urgent solutions needed to shore up family finances ahead of the winter are not yet being put in place.”

She added that the interest rate rises will also put pressure on homeowners.

Bank Governor Andrew Bailey insisted that the increase from 1.25 per cent to 1.75 per cent – taking rates to the highest level since January 2009 – was necessary to get inflation under control.

“Inflation hits the least well-off hardest. But if we don’t act now to prevent inflation becoming persistent, the consequences later will be worse, and will require larger increases in interest rates,” he said.

The Bank said the economy will at least escape the depths of the 2008 or Covid-19 crashes, which took a much bigger dent out of GDP.

The drop will be more comparable to the recession in the early 1990s.

Mr Bailey said there is an “economic cost to the war” in Ukraine.

“But I have to be clear, it will not deflect us from setting monetary policy to bring inflation back to the 2 per cent target,” he said.

The Bank’s latest forecast is that inflation will come back under control in 2023, dropping below 2 per cent towards the end of the year.

It also predicts that unemployment will start to rise again next year.

GDP is set to grow by 3.5 per cent this year, the Bank said, revising its previous 3.75 per cent projection downwards. It will then contract 1.5 per cent next year, and a further 0.25 per cent in 2024.

The decision to set interest rates at 1.75 per cent was almost unanimous. Only one member of the MPC, which sets rates, voted for a smaller base rate rise.

The forecasts are likely to feature in the ongoing Conservative Party leadership contest.

Frontrunner Liz Truss has said she plans to re-examine the Bank’s independent mandate to ensure it has a “tight enough focus on the money supply and on inflation”.