Thousands of people in Italy and France have joined protests to show their opposition to plans to require vaccination cards for normal social activities, such as dining indoors at restaurants, visiting museums or cheering in sports stadiums.

Shouts of “liberty” echoed through the streets and squares of the two countries during the protests.

Leaders in both nations see the cards, dubbed the “green pass” in Italy and the “health pass” in France, as necessary to boost vaccination rates and persuade the undecided.

Italian premier Mario Draghi likened the anti-vaccination message from some political leaders to “an appeal to die”.

The looming requirement is working, with vaccination requests booming in both countries.

Still, there are pockets of resistance by those who see it as a violation of civil liberties or have concerns about vaccine safety.

European nations in general have made strides in their vaccination rates in recent months, with or without incentives. No country has made the shots mandatory, and campaigns to persuade the undecided are a patchwork.

Denmark pioneered vaccine passes with little resistance. Belgium will require a vaccine certificate to attend outdoor events with more than 1,500 people by mid-August and indoor events by September. Germany and Britain have so far resisted a blanket approach, while vaccinations are so popular in Spain that incentives are not deemed necessary.

In France and Italy, demonstrations against vaccine passes or virus restrictions in general are bringing together otherwise unlikely allies, often from the political extremes. They include far-right parties, campaigners for economic justice, families with small children, those against vaccines and those who fear them.

Many say vaccine pass requirements are a source of inequality that will further divide society, and they draw uneasy historic parallels.

“We are creating a great inequality between citizens,” said one protester in Verona, who identified himself only as Simone because he said he feared for his livelihood. “We will have first-class citizens, who can access public services, the theatre, social life, and second-class citizens, who cannot.”

The French health pass is required at museums, cinemas and tourist sites, and comes into effect for restaurants and trains on August 9. To get it, people must be fully vaccinated, have a recent negative test, or proof they recently recovered from Covid-19.

Italy’s requirements are less stringent. Just one vaccine dose is required, and it applies to outdoor dining, cinemas, stadiums, museums and other gathering places from August 6. Expanding the requirement to long-distance transport is being considered.

A negative test within 48 hours or proof of having recovered from the virus in the last six months also provide access.

Vaccine demand in Italy increased by as much as 200% in some regions after the government announced the green pass, according to the country’s special commissioner for vaccinations.

In France, nearly five million got a first dose and more than six million got a second dose in the two weeks after President Emmanuel Macron announced that the virus passes would be expanded to restaurants and many other public venues. Before that, vaccination demand had been waning for weeks.

A full 15% of Italians remain resistant to the vaccine message: 7% identifying themselves as undecided, and 8% as anti-vaccine, according to a survey by SWG.

The biggest reasons for hesitating or refusing to get vaccinated, cited by more than half of respondents, are fears of serious side-effects and concerns that the vaccines have not been adequately tested. Another 25% said they do not trust doctors, 12% said they do not fear the virus, and 8% deny it exists.

This leaves some hard-to-penetrate segments of the population.

About two million Italians over 60 remain unvaccinated, despite being given precedence in the spring. Thousands remain unprotected in Lombardy alone, the epicentre of Italy’s outbreak.

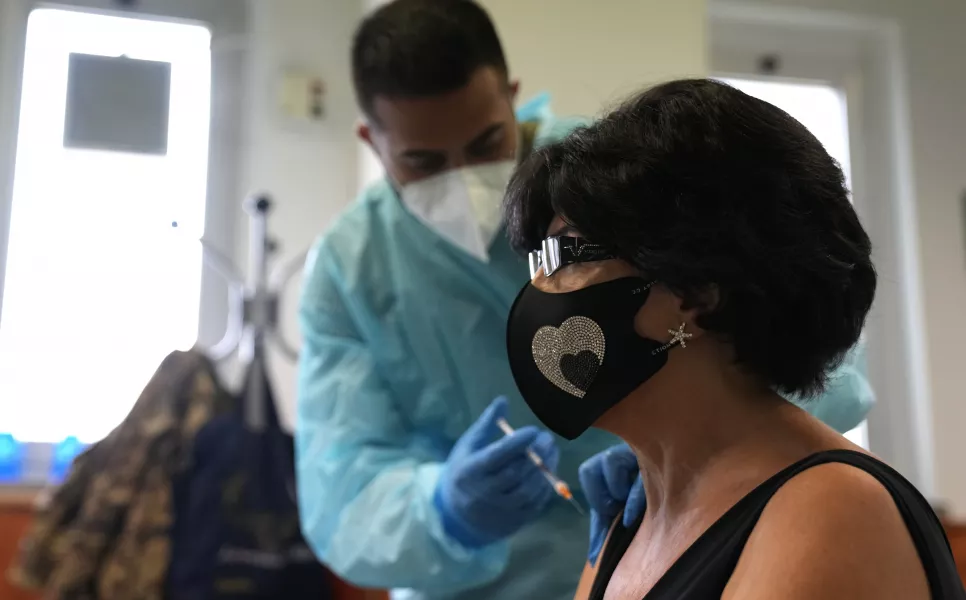

The city of Milan is dispatching mobile vans with vaccines and other supplies to a different neighbourhood every day. They reach out to the reluctant with flyers and social media posts, vaccinating 100-150 people a day with the single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

Businesses in Italy and France are grudgingly accepting the passes, amid concern over how private companies can enforce public policy. Denmark’s experience suggests compliance gets easier with time – and rising vaccination rates.

“The first couple of months weren’t good,” recalls Sune Helmgaard, whose restaurant in Copenhagen serves classic Danish fare. In the spring, vaccination rates were still low and customers could not always get tested in time.

But with more than 80% of eligible Danes having received at least one shot and more than 60% fully vaccinated, his business is back to pre-pandemic levels.

“People feel safer,” he said. “So Danes are quite happy to show their pass.”