The Vatican has given the green light for Catholics to continue flocking to a southern Bosnian village where children reported seeing visions of the Virgin Mary, offering its approval for devotion in one of the most contested aspects of Roman Catholic practice in recent years.

In a detailed analysis after nearly 15 years of study, the Vatican’s doctrine office did not declare that the reported apparitions in Medjugorje were authentic or of supernatural origin.

And it flagged concerns about contradictions in some of the “messages” the alleged visionaries say they have received over the years.

But in line with new Vatican criteria in place this year, the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith ruled that the “spiritual fruits” stemming from the Medjugorje experience more than justified allowing the faithful to organise pilgrimages there and permit public acts of devotion.

The decision essentially overrules the original doubts about the alleged apparitions at Medjugorje by the region’s past diocesan bishops.

And it ignores current concerns about the economic interests that have turned Medjugorje into a thriving destination for religious tourists.

But with Pope Francis’ approval, the doctrine office decided that “the abundant and widespread fruits, which are so beautiful and positive” justified its decision.

It said doing so “highlights that the Holy Spirit is acting fruitfully for the good of the faithful in the midst of this spiritual phenomenon”.

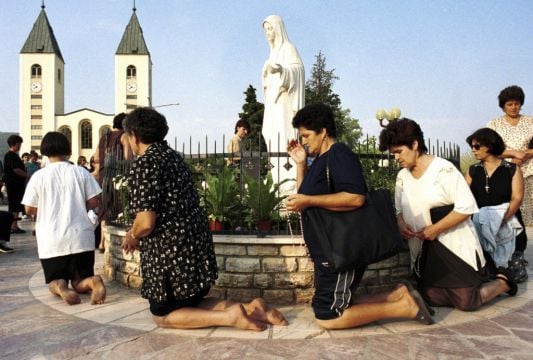

In 1981, six children and teenagers reported seeing visions of the Madonna on a hill in the village of Medjugorje, located in the wine-making region of southern Bosnia.

Some of those original “seers” have claimed the visions have occurred regularly since then, even daily, and that Mary sends them messages.

As a result, Medjugorje has become a major European pilgrimage destination for Christian believers, attracting millions of people over the years.

Last year alone, 1.7 million Eucharistic wafers were distributed during Masses there, according to statistics published on the shrine’s website, a rough estimate of the numbers of Catholics who visited.

However, unlike at the more well-known and established Catholic sanctuaries in Fatima, Portugal or Lourdes, France, the alleged apparitions at Medjugorje were never declared authentic by the Vatican.

And over the years, the area’s local diocesan bishops and some Vatican officials had cast doubt on the reliability and motivations of the “seers,” because of concerns that economic interests may have been driving their reports of continued visions.

Two experts tapped by Pope Benedict XVI to study the Medjugorje concluded the phenomenon was “demonic” in origin.

Even Francis in 2017 expressed doubts about their messages, saying: “I prefer Our Lady to be a mother, our mother, and not a telegraph operator who sends out a message every day at a certain time.”

Religious tourism has become an important part of the local economy, with an entire industry catering to pilgrims: hotels, private accommodations, family-run farm businesses, even sports complexes and camping sites.

Their growth has contributed to the surrounding municipality’s financial well-being after the Bosnian war in the 1990s devastated the economy.

In its assessment, the Vatican doctrine office recalled that in May of this year it announced it was no longer in the business of authenticating alleged apparitions and other supposedly supernatural phenomena that have attracted Catholics for centuries, including statues that allegedly weep blood or stigmatas that are said to erupt spontaneously on hands or feet.

The new criteria envisage six main outcomes, with the most favourable being that the church issues a noncommittal doctrinal green light, a so-called “nihil obstat”, which means there is nothing about the event that is contrary to the faith, and therefore Catholics can express devotion to it.

With Francis’ approval, the Vatican on Thursday gave that “nihil obstat” to Medjugorje.

In its analysis, the Vatican listed what it called the many spiritual benefits that have been associated with pilgrimages to the site, including people deciding that they want to become priests or nuns, couples reconciling after troubles in marriage, healings after prayer and new works of charity caring for orphans and drug addicts.

It listed no example of any negative experiences associated with Medjugorje, or reference to concerns raised by previous diocesan bishops of Mostar who had declared the apparitions were false.

Nor did it mention that the priest most closely associated with Medjugorje and the six “visionaries” was defrocked by the Vatican in 2009 for, among other things, spreading false doctrine.

The Vatican did seem to want to distance the place from the people behind the alleged apparitions, stressing that these benefits have not occurred as a result of meetings with the alleged visionaries but rather “in the context of pilgrimages to the places associated with the original events”.

And in its 17-page document, it used nearly four pages to list concerns about problems in some of the thousands of individual messages the alleged visionaries have received, including cases where the message contradicted aspects of Catholic doctrine.

The decision will surely impact Medjugorje, which lies in the municipality of Citluk, one of the smallest in Bosnia with some 18,000 residents but economically well-off.

The municipality has declared that tourism is key for its development, largely thanks to Medjugorje, and hosts various festivals and gatherings each year organised by Christian humanitarian organisations drawn to the place.

Municipal workers say 2024 could be a record year, because Christian pilgrims are tending to stay away from Israel because of the war, and are opting for Medjugorje instead.

“Medjugorje means a lot, all economic sectors lean on Medjugorje,” said Ante Kozina, the tourism association chief. “It is a growth generator for the entire municipality.”