An international arrest warrant for Russia president Vladimir Putin raises the prospect of the man whose country invaded Ukraine facing justice, but it complicates efforts to end that war in peace talks.

Both justice and peace appear to be only remote possibilities today, and the conflicting relationship between the two is a quandary at the heart of a decision on March 17th by the International Criminal Court (ICC) to seek the Russian leader’s arrest.

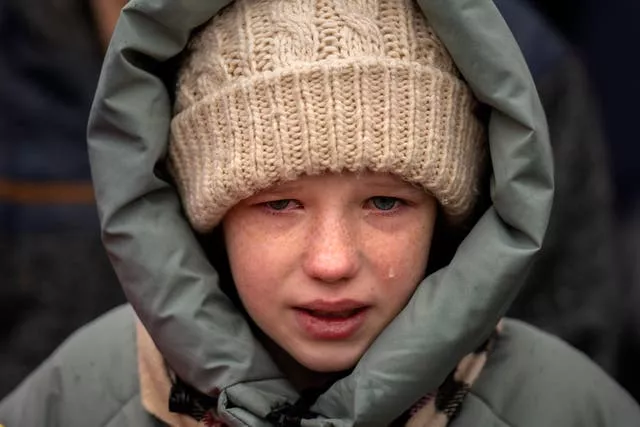

Judges in The Hague found “reasonable grounds to believe” that Mr Putin and his commissioner for children’s rights were responsible for war crimes, specifically the unlawful deportation and unlawful transfer of children from occupied areas of Ukraine to Russia.

As unlikely as Mr Putin sitting in a Hague courtroom seems now, other leaders have faced justice in international courts.

Former Serbian strongman Slobodan Milosevic, a driving force behind the Balkan wars of the 1990s, went on trial for war crimes, including genocide, at a United Nations tribunal in The Hague after he lost power. He died in his cell in 2006 before a verdict could be reached.

Serbia, which wants European Union membership but has maintained close ties to Russia, is one of the countries that has criticised the ICC’s action. The warrants “will have bad political consequences” and create “a great reluctance to talk about peace (and) about truce” in Ukraine, populist Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic said.

Others see consequences for Mr Putin, and for anyone judged guilty of war crimes, as the primary desired outcome of international action.

“There will be no escape for the perpetrator and his henchmen,” European Union leader Ursula von der Leyen said on Friday in a speech to mark the one-year anniversary of the liberation of Bucha, the Ukraine town that saw some of the worst atrocities in the war.

“War criminals will be held accountable for their deeds,” she added.

Hungary did not join the other 26 EU members in signing a resolution in support of the ICC warrant for Mr Putin. The government’s chief of staff, Gergely Gulyas, said Hungarian authorities would not arrest the Russian leader if he were to enter the country.

Mr Gulyas called the warrants “not the most fortunate because they lead toward escalation and not toward peace”.

Mr Putin appears to have a strong grip on power, and some analysts suspect the warrant hanging over him could provide an incentive to prolong the fighting.

“The arrest warrant for Putin might undermine efforts to reach a peace deal in Ukraine,”

Daniel Krcmaric, an associate professor of political science at Northwestern University, said: “The arrest warrant for Putin might undermine efforts to reach a peace deal in Ukraine.”

One potential way of easing the way to peace talks could be for the United Nations Security Council to call on the International Criminal Court to suspend the Ukraine investigation for a year, which is allowed under Article 16 of the Rome Statute treaty that created the court.

But that appears unlikely, said Mr Krcmaric, whose book The Justice Dilemma deals with the tension between seeking justice and pursuing a negotiated end to conflicts.

“The Western democracies would have to worry about public opinion costs if they made the morally questionable decision to trade justice for peace in such an explicit fashion,” he said, adding that Ukraine is also unlikely to support such a move.

Russia immediately rejected the warrants. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said Moscow does not recognise the ICC and considers its decisions “legally void”. Dmitry Medvedev, deputy head of Russia’s Security Council, which is chaired by Mr Putin, suggested the ICC headquarters on the Netherlands’ coastline could become a target for a Russian missile strike.

Alexander Baunov, an analyst with the Carnegie Endowment, observed in a commentary that the arrest warrant for Mr Putin amounted to “an invitation to the Russian elite to abandon Putin” that could erode his support.

While welcoming the warrants for Mr Putin and his commissioner for children’s rights, rights groups also urged the international community not to forget the pursuit of justice in other conflicts.

“The ICC warrant for Putin reflects an evolving and multifaceted justice effort that is needed elsewhere in the world,” Human Rights Watch associate international justice director Balkees Jarrah said in a statement.

“Similar justice initiatives are needed elsewhere to ensure that the rights of victims globally — whether in Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Myanmar, or Palestine — are respected.”