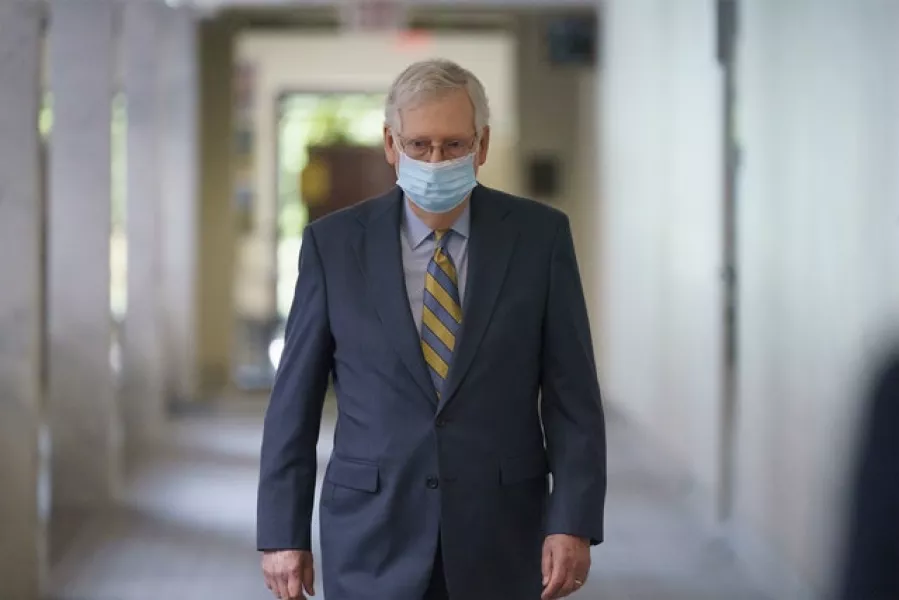

Republicans are eyeing a vote in late October, though Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell has not yet said for certain whether a final vote will come before or after the November 3 election.

A confirmation vote so close to a presidential election would be unprecedented, creating significant political risk and uncertainty for both parties. Early voting is under way in some states in the race for the White House and control of Congress.

Here we look at the confirmation process and what we know and don’t know about what’s to come:

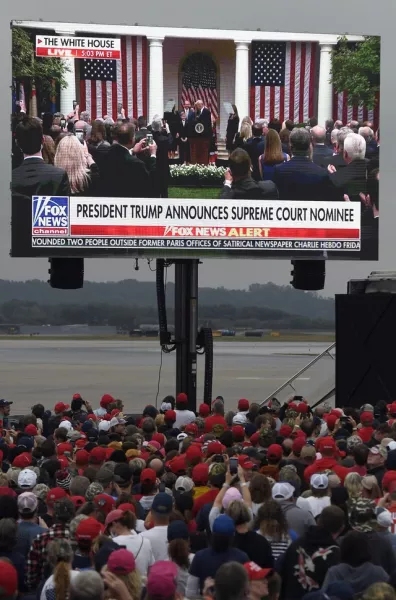

Ms Barrett has been a federal judge in Indiana since 2017, when Mr Trump nominated her to the Chicago-based 7th US Circuit Court of Appeals. She was previously a long-standing University of Notre Dame law professor and clerked for the late Justice Antonin Scalia, whom she called her “mentor” as she accepted Mr Trump’s nomination on Saturday. At the age of 48, she would be the youngest justice on the current court if confirmed.

Ms Barrett’s three-year judicial record shows a clear and consistent conservative bent. She is a committed Roman Catholic as well as a firm devotee of Scalia’s favoured interpretation of the Constitution known as originalism.

Republicans have widely praised her, while Democrats worry her votes could chip away at the Roe v Wade decision legalising abortion and erode health care protections. They argue that her philosophy is too conservative and rigid.

Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Lindsey Graham said his panel will hold four days of confirmation hearings during the week of October 12.

Once the committee approves the nomination, it goes to the Senate floor for a final vote. This could all happen by November 3 if the process goes smoothly. Mr Graham said he hopes the committee can move the nomination to the Senate floor by the week of October 26 for a confirmation vote.

Ms Barrett is expected to make her first appearance on Capitol Hill on Tuesday, meeting with Mr McConnell, Mr Graham and other members.

Republicans are privately aiming to hold the final vote in the last week of October, but acknowledge the tight timeline and say they will need to see how the hearings go. Mr McConnell has been careful not to say when he believes the final confirmation vote will happen, other than “this year”.

Senate Republicans are mindful of their last confirmation fight in 2018, when Christine Blasey Ford’s allegations of a teenage sexual assault almost derailed Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination. The process took longer than expected after Republicans agreed to allow Ms Ford to testify. Mr Kavanaugh, who denied the allegations, was eventually confirmed in a 50-48 vote.

Mr McConnell does appear to have the votes, for now. Republicans control the Senate by a 53-47 margin, meaning he could lose up to three Republican votes and still confirm a justice, if vice president Mike Pence were to break a 50-50 tie.

At this point, Mr McConnell seems to have lost the support of two Republicans — Maine senator Susan Collins and Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski, both of whom have said they do not think the Senate should take up the nomination before the election. Ms Collins has said the next president should fill the court seat, and she will vote “no” on Mr Trump’s nominee on principle.

There isn’t much they can do. Republicans are in charge and make the rules, and they appear to have the votes for Mr Trump’s nominee, at least for now. Democrats have vowed to oppose the nomination, and they are likely to use an assortment of delaying tactics. None of those efforts can stop the nomination, however.

But Democrats will also make the case against the nomination to voters as the confirmation battle stretches into the final weeks — and maybe even the final days — of the election season. They say health care protections and abortion rights are on the line, and argue the Republicans’ vow to move forward is “hypocrisy” after Mr McConnell refused to consider president Barack Obama’s nominee, Judge Merrick Garland, several months before the 2016 election.

Republicans are defending 25 of the 38 Senate seats that are on the ballot this year, and many of their vulnerable members were eager to end the autumn session and return home to campaign. The Senate was originally scheduled to recess in mid-October, when the hearings are now expected to begin.

While some senators up for re-election, like Ms Collins, have opposed an immediate vote, others are using it to bolster their standing with conservatives. Several GOP senators in competitive races this year – including Cory Gardner in Colorado, Martha McSally in Arizona, Kelly Loeffler in Georgia and Thom Tillis in North Carolina – quickly rallied to Mr Trump, calling for swift voting.

Supreme Court nominations have taken around 70 days to move through the Senate, though the last, of Mr Kavanaugh, took longer, and others have taken less time. The election is fewer than 40 days away.

Could the Senate fill the vacancy after the election?

Yes. Republicans could still vote on Mr Trump’s nominee in what’s known as the lame-duck session that takes place after the November election and before the next Congress takes office on January 3. No matter what happens in this year’s election, Republicans are still expected to be in charge of the Senate during that period.

The Senate would have until January 20, the date of the presidential inauguration, to act on Mr Trump’s nominee. If Mr Trump were re-elected and Ms Barrett had not been confirmed by the inauguration, he could renominate her as soon as his second term began.

He did. Mr McConnell stunned Washington in the hours after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia in February 2016 when he announced the Senate would not vote on Mr Obama’s potential nominee because the voters should have their say by electing the next president.

Mr McConnell’s strategy paid off, royally, for his party. Mr Obama nominated Mr Garland to fill the seat, but he never received a hearing or a vote. Soon after his inauguration, Mr Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch to fill Mr Scalia’s seat.

Mr McConnell says it’s different this time because the Senate and the presidency are held by the same party, which was not the case when a vacancy opened under Mr Obama in 2016. It was a rationale Mr McConnell laid out during the 2016 fight, and other Republican senators have invoked it this year when supporting a vote on Mr Trump’s nominee.

Democrats say this reasoning is laughable and the vacancy should be kept open until after the inauguration.