The sudden death of Russian president Vladimir Putin’s most formidable antagonist has left an open wound in Russia’s political opposition.

Alexei Navalny (47) was the Kremlin’s best-known critic at home and abroad. Before he died in a penal colony on Friday, the anti-corruption crusader, protest organiser and politician with an arch sense of humour became the subject of an award-winning documentary. His channels on YouTube had millions of subscribers.

Mr Navalny was also the first opposition leader in Russia to receive a lengthy prison sentence in recent years. There would be others, heralding a crackdown on dissent that became more punishing with the invasion of Ukraine.

In the three years since Mr Navalny lost his freedom, multiple prominent dissidents were imprisoned, while others fled Russia under pressure.

Many of them nevertheless persisted in challenging Mr Putin — organising abroad, pushing for sanctions on Russia, supporting like-minded Russians in exile or continuing to speak out from behind bars.

These are some of the key remaining figures:

Navalny’s core team

Colleagues at the Anti-Corruption Foundation, which Mr Navalny founded in 2011 to expose political corruption, and his other close associates often had to work without him. Even before he was imprisoned in January 2021, Mr Navalny was subject to regular arrests and long jail stints.

In 2020, he was poisoned with a nerve agent, spent 18 days in a coma and recuperated in Germany for weeks. His prison term included more than 300 days in isolation, with communication possible but difficult from a punishment cell.

His closest associates – top strategist Leonid Volkov, head of investigations Maria Pevchikh, foundation director Ivan Zhdanov and spokesperson Kira Yarmysh – also faced unrelenting pressure and prosecution in Russia.

In recent years, all left the country and worked from abroad, providing political commentary and the foundation’s signature YouTube exposes of political corruption.

They kept pushing for Mr Navalny’s release from prison, organised protests and mounted a campaign to undermine Mr Putin’s image in Russia ahead of a presidential election he is almost certain to win next month.

“Alexei was awesome,” Mr Volkov wrote Sunday on X, formerly Twitter. “He was a natural politician, very talented, very efficient. And from himself and from everyone around him, he demanded one thing: not to throw in the towel, not to give up, not to despair. … This is what he wants from us now. His life’s work must prevail.”

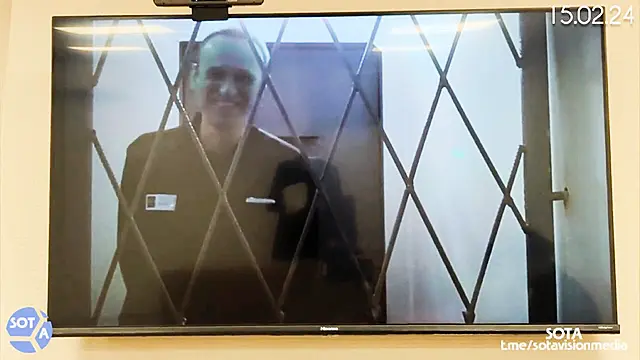

Vladimir Kara-Murza

Once a journalist and now a prominent opposition politician, British-Russian Vladimir Kara-Murza, 42, received the longest single sentence handed to a Kremlin critic in Putin’s Russia — 25 years on charges of treason. He is serving the sentence in a Siberian penal colony and has been repeatedly placed in solitary confinement.

Mr Kara-Murza was an associate of Russian opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, another fierce Putin critic who was assassinated near the Kremlin in 2015.

A few years before that, Mr Kara-Murza and Mr Nemtsov lobbied for passage of the Magnitsky Act in the US. The law was a response to the prison death of Russian lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, who had exposed a tax fraud scheme. It authorised Washington to impose sanctions on Russians deemed to be human rights violators.

Mr Kara-Murza survived what he believes were attempts to poison him in 2015 and 2017 but kept returning to Russia despite concerns that it might be unsafe for him to do so.

Since his April 2022 arrest, he has continued to speak out against Mr Putin and the war in Ukraine in multiple opinion columns and letters written from behind bars. His wife, Yevgenia, has also actively campaigned to secure freedom for him and other jailed Kremlin critics.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Mikhail Khodorkovsky (60) is a former tycoon turned Russian opposition figure in exile. Mr Khodorkovsky spent a decade in prison in Russia on charges widely seen as political revenge for challenging Mr Putin’s rule in the early 2000s.

He was released in 2013, shortly before Russia hosted the 2014 Winter Olympics in the Black Sea resort of Sochi. A surprise pardon from Mr Putin on the eve of the Olympics was widely seen as an effort by the Kremlin to improve Russia’s image in the West.

Mr Khodorkovsky was flown to Germany and later settled in London. From exile, he launched Open Russia, an opposition group that ran its own news outlet, supported candidates in various elections, provided legal aid to defendants facing politically motivated prosecutions and had an educational platform.

Open Russia and its activists the country faced constant pressure from the authorities; some were prosecuted in Russia, and one of its leaders, Andrei Pivovarov, is currently serving a four-year prison term.

The group eventually shut down, but Mr Khodorkovsky continued his vocal criticism of the Kremlin. After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine two years ago this week, he and other prominent Putin critics, including chess legend Garry Kasparov and former politician Dmitry Gudkov, formed the Antiwar Committee, a broad opposition alliance that opposes the invasion and seeks to undermine Mr Putin.

Ilya Yashin

Ilya Yashin (40) refused to leave Russia despite the unprecedented pressure authorities applied to stifle dissent. He said that getting out of the country would undermine his value as a politician.

Mr Yashin, an uncompromising member of a Moscow municipal council, was a vocal ally of Mr Navalny. He was eventually arrested in June 2022 and later sentenced to eight and a half years in prison for “spreading false information” about the Russian military, a criminal offence since March 2022.

The harsh sentence did not silence his sharp criticism of the Kremlin. Mr Yashin’s associates regularly update his social media pages with messages he relays from prison.

His YouTube channel has more than 1.5 million subscribers. In a prison interview with The Associated Press in September 2022, Mr Yashin urged ordinary Russians to help spread the word, too.

“Demand for an alternative point of view has appeared in society,” Mr Yashin told the AP in written answers from behind bars.