The Apollo 16 capsule is dusty decades after it carried three astronauts to the Moon.

Cobwebs cling to the spacecraft and business cards, a pencil, money, a spoon and even a tube of lip balm litter the floor of the giant case that protects the space antique in a museum.

The Covid-19 pandemic meant a break in the normal routine of cleaning the display at the US Space and Rocket Centre, near Nasa’s Marshall Space Flight Centre, but workers are now sprucing up the spacecraft for the 50th anniversary of its April 1972 flight.

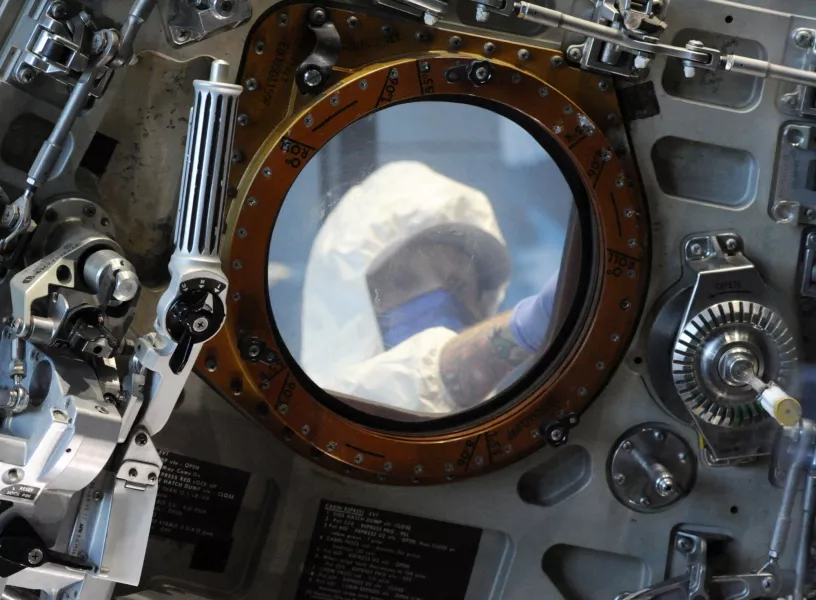

Delicately using microfibre towels, extension poles, brushes, dust-catching wands and vacuums, a crew recently cleaned the 6.5-ton, nearly 11ft-tall capsule and wiped down its glass enclosure, located beneath a massive Saturn V rocket suspended from the ceiling.

They also removed dozens of items that people had stuck through cracks in the case.

Apart from overseeing the cleaning, consulting curator Ed Stewart taught museum staff how to maintain the capsule, which is on loan from the Smithsonian Institution and has been displayed in the “rocket city” of Huntsville since the 1970s.

Brushing dust off the side of the capsule while dressed in protective clothing, Mr Stewart said the command module is in “pretty good shape” considering its age and how long it has been since the last cleaning about three years ago.

“I’m pleased to see that there’s not … heavy layers of dust. I’ve not seen a lot of insect debris or anything like that, so I take that as a very positive sign,” he said.

Richard Hoover, a retired Nasa astrobiologist who is a lecturer at the museum, remembered a time decades ago when visitors could touch the spacecraft. Some even picked off pieces of the charred heat shield that protected the ship from burning up while re-entering Earth’s atmosphere, he said.

“This is really quite a travesty because they don’t realise that this is a tremendously important piece of space history,” he said.

Conservation procedures changed as preservationists realised that a ship built to withstand the rigours of space travel did not hold up well under the constant touch of tourists, Mr Stewart said. That is why the case surrounding the capsule is sealed.

“Making it last for 1,000 years was not on the engineer’s list of requirements for developing these to get the astronauts to the Moon and back safely,” he said.

Perched on top of columns, the capsule – nicknamed “Casper” during the flight – is tilted so visitors can look inside the open hatch and see controls and the metal-framed seats where astronauts Ken Mattingly, John Young and Charlie Duke travelled to the Moon and back.

Mr Duke, who walked on the Moon with Mr Young while Mr Mattingly piloted the capsule, is expected to attend a celebration this spring marking the 50th anniversary of the flight’s lift-off on April 16 1972.

The capsule was cleaned and any potentially hazardous materials were removed after the flight, but reminders of its trip to the Moon remain inside. Leaning through the hatch to check for dust, Mr Stewart pointed to a few dark spots over his head.

“That’s the crew’s fingerprints and handprints on there,” he said.

Workers plan to further seal the capsule’s case so visitors will not be able to deposit anything inside, but they were careful not to do too much to Apollo 16 itself.

While it would be easy enough to scrub down the spaceship with elbow grease, doing so would destroy the patina that links it to history, Mr Stewart said.

“You don’t want to lose any of that, because that is all part of the saga of the mission. If you clean it, it’s gone. It’s that extra texture of history that just sort of is lost to the ether if you make a mistake,” he said.