The global death toll from coronavirus topped three million on Saturday, amid repeated setbacks in the worldwide vaccination campaign and a deepening crisis in places such as Brazil, India and France.

The number of lives lost, as compiled by Johns Hopkins University, is about equal to the population of Kyiv, Ukraine; Caracas, Venezuela; or metropolitan Lisbon, Portugal.

And the true number is believed to be significantly higher because of possible government concealment and the many cases overlooked in the early stages of the outbreak that began in Wuhan, China, at the end of 2019.

When the world in January passed the bleak threshold of two million deaths, immunisation drives had just started in Europe and the United States.

Today, they are under way in more than 190 countries, though progress in bringing the virus under control varies widely.

While the campaigns in the US and the UK Britain have hit their stride and people and businesses there are beginning to contemplate life after the pandemic, other places, mostly poorer countries but some rich ones as well, are lagging behind in and have imposed new lockdowns and other restrictions as virus cases soar.

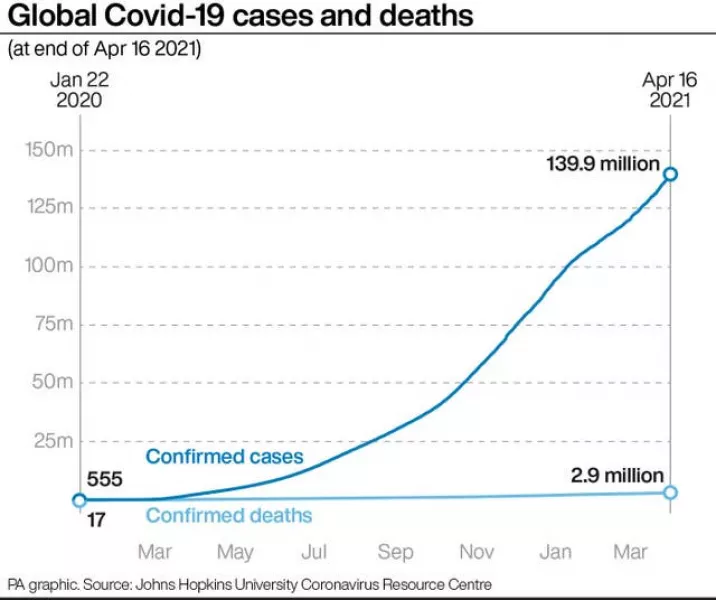

Worldwide, deaths are on the rise again, running at about 12,000 per day on average, and new cases are climbing too, eclipsing 700,000 a day.

“This is not the situation we want to be in, 16 months into a pandemic, where we have proven control measures,” said Maria Van Kerkhove, one of the World Health Organisation’s leaders on Covid-19.

In Brazil, where deaths are running at about 3,000 per day, accounting for one-quarter of the lives lost worldwide in recent weeks, the crisis has been likened to a “raging inferno” by one WHO official.

A more contagious variant of the virus has been rampaging across the country.

As cases surge, hospitals are running out of critical sedatives.

As a result, there have been reports of some doctors diluting what supplies remain and even tying patients to their beds while breathing tubes are pushed down their throats.

The slow vaccine rollout has crushed Brazilians’ pride in their own history of carrying out huge immunisation campaigns that were the envy of the developing world.

The situation is similarly dire in India, where cases spiked in February after weeks of steady decline, taking authorities by surprise.

In a surge driven by variants of the virus, India saw more than 180,000 new infections in one 24-hour span during the past week, bringing the total number of cases to more than 13.9 million.

Problems that India had overcome last year are coming back to haunt health officials. Only 178 ventilators were free on Wednesday in New Delhi, a city of 29 million, where 13,000 new infections were reported the previous day.

The challenges facing India reverberate beyond its borders since the country is the biggest supplier of shots to Covax, the UN-sponsored programme to distribute vaccines to poorer parts of the world.

Last month, India said it would suspend vaccine exports until the virus’s spread inside the country slows.

The WHO recently described the supply situation as precarious. Up to 60 countries might not receive any more shots until June, by one estimate.

To date, Covax has delivered about 40 million doses to more than 100 countries, enough to cover barely 0.25% of the world’s population.

Globally, about 87% of the 700 million doses dispensed have been given out in rich countries. While one in four people in wealthy nations have received a vaccine, in poor countries the figure is one in more than 500.

In Europe, countries are feeling the brunt of a more contagious variant that first ravaged Britain and has pushed the continent’s Covid-19-related death toll beyond one million.

Close to 6,000 gravely ill patients are being treated in French critical care units, numbers not seen since the first wave a year ago.